Last Monday, Federal Judge Jed Rakoff issued a potentially precedent-setting challenge to the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) when he rejected the $285 million settlement between the agency and Citigroup. The bank is charged with negligence related to its misleading sale of toxic mortgage-backed securities, which ultimately cost investors nearly $700 million but earned the bank a handsome profit of almost $160 million.

Analysts have focused on the immediate and narrow concern of how the SEC and Citigroup will respond to this challenge and on second-guessing what may satisfy Judge Rakoff. Three options exist: the agency could renegotiate a deal with the bank for a higher settlement and insert vague (and non-incriminating) language hinting at the bank’s culpability; it could allow the case to go to trial; or it could appeal the Judge’s decision. Some even suggest that the ruling may result in the SEC pursuing more cases administratively in the future.

Rather than adding to these ongoing media and expert analyses on the immediate response of the SEC and Citigroup to Judge Rakoff’s ruling, we take a broader perspective. SEC v. Citigroup can be seen in the context of the intimate relationship between the agency and the powerful banks it regulates, one which has prevailed for years and weakened the regulatory power of the SEC.

The financial crisis and subsequent call for reform provided ample opportunity to tackle such undue influence and regulatory capture, which occurs when the regulator is unduly influenced by the interests of regulated entities. At the beginning of the new administration and during the early stages of the Dodd-Frank reform bill preparation, a rebalancing of power between the weakened regulator and powerful financial institutions was expected.

Yet, once the bill was adopted reality began to sink in. The reform bill failed to directly address the problem of banks that were too big to fail, and left crucial implementation matters to the discretion of weak regulatory agencies such as the SEC. It seemed that power shifted back from Washington to Wall Street again.

Rakoff’s challenge to the SEC exposes yet another example of how old power balances that favor financial institutions remain alive and well. The main question is not how the SEC can reword its settlement with Citigroup to satisfy judge Rakoff, but rather whether the judge’s ruling will serve as a wake-up call to the weak regulatory regime governing the behavior of financial institutions and prompt concrete changes to the rules of the game.

The SEC has a history of regulatory capture

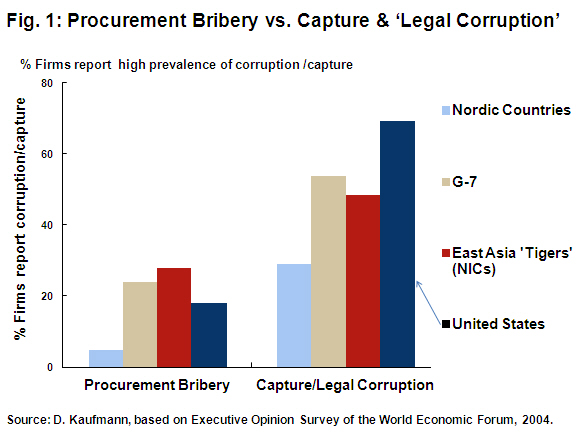

Whether covert or overt, elements of regulatory capture have been evident for some time. In the decade leading up to the financial crisis, deregulation in the U.S. financial sector weakened regulatory agencies. More generally, seven years ago I codified the extent of “state capture” and “legal corruption” through a survey of enterprises in over 100 countries. The extent of capture afflicting the U.S. was very high; it not only rated well below other industrialized countries, but found itself among the bottom half worldwide (figure 1). But at that peak time of financial exuberance and deregulation, there was little appetite to take such data seriously.

It got worse. These data were collected months before an infamous meeting between bankers and the SEC in April 2004 when the SEC readily agreed to significantly relax its regulatory stance vis-a-vis the largest investment banks, allowing them to amass massive amounts of debt. In return, once the agency set up its supervisory program, the banks would submit reviews and restrictions on excessively risky activities. Yet the SEC hired only seven people to examine companies with combined assets of more than $4 trillion and completed no inspections after 2007.

Furthermore, preceding the financial crisis the SEC became aware that Bernard Madoff, who had served on the commission’s advisory committee and had been previously reported for securities violations, was mismanaging his customers’ funds in the tens of billions of dollars. Yet the agency failed to probe deeper and unmask his Ponzi scheme. The SEC also neglected to take action against financier R. Allen Stanford, who swindled investors out of $8 billion, although allegations of fraud and possible money laundering had been levied against him in the past.

Expectations of change were not realized

The onset of the financial crisis revealed the weakness of the financial sector and the extent to which regulators had been captured. It spurred public outrage and calls for change. When the new administration entered office it brought with it a clear appreciation for the problem of capture. As early as 2007, then Senator Obama, during a major address at Nasdaq in New York City, recognized that “turning a blind eye to cronyism in our midst put us all in jeopardy” and that “we [were] going to have to adapt our institutions to a new world.”

Over three years later, regulatory reforms were adopted through the Dodd-Frank bill, which, at least on paper, signaled a move in the right direction toward stronger regulations and the potential for somewhat reduced capture. Yet, recent events are exposing weaknesses in Dodd-Frank. The bill failed to address crucial implementation details and was vague in some regulatory matters, leaving discretion in the hands of weak regulators. Since the mid-term congressional elections last year, lobbyists for large financial institutions and their allies in Congress have been working hard to keep, as intact as possible, the deregulated status quo that prevailed prior to the financial crisis.

It is now evident that if not for the Federal Reserve Boards’ lack of transparency in supporting large banks during the crisis, the Dodd-Frank bill may have had a better chance at addressing the undue influence and systemic risk posed by these large financial institutions. The extent to which large banks teetered on the edge of collapse in 2008 and 2009 has only now come to light. This week, Bloomberg revealed that by March 2009 the Federal Reserve had secretly provided nearly $7.8 trillion in emergency funds to rescue the financial system, dwarfing the publicly known $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). The trouble with this secret bailout is not the Fed’s emergency actions, but rather that the information remained so closely guarded for so long and that the Fed fought against its disclosure.

This secrecy may have been initially warranted to prevent further panic, but the lack of transparency in the medium-term had a significant impact on regulatory reform. Had the information been disclosed earlier, including to members of Congress and the public, the evidence of systemic risk posed by large banks may have persuaded some to adopt a tougher Dodd-Frank bill. A stronger bill may have more directly addressed the problem of large banks, and in this context, further empowered regulatory agencies such as the SEC. In fact, had the details of the Fed’s bailout been disclosed, there may have been more support in Congress to break up the biggest banks. Lobbyists for the largest recipients of relief funds made a winning case that such a breakup would punish “successful” institutions.

Regulatory capture of the SEC today impacts enforcement

The close ties between banks and the SEC is symptomatic of the sector’s influence over the regulator. A study by the Project on Government Oversight found that in the past five years, 219 former SEC employees filed nearly 800 disclosure statements for representing their clients’ dealings with the agency, and of these, about half (403) were filed by people who worked for the SEC’s enforcement division. Because former employees are only required to file such disclosures for two years after leaving the SEC, these figures only capture the most recent instances. Even the regulator’s top enforcement official has moved back and forth between the Justice Department, Deutsche Bank and the SEC.

Such close ties may ultimately affect enforcement. An internal investigation found that a former SEC official blocked the agency’s investigation of R. Allen Stanford for nearly seven years, and then went on to work for him. More recently, the SEC’s head enforcement official was investigated (but cleared) after Citigroup hired his former boss to participate in its defense against charges unrelated to the case before Judge Rakoff. Negotiations between the parties resulted in the charges against two executives being reduced. In an open investigation, the SEC’s inspector general is looking into allegations that the frequent hiring of former SEC attorneys by a particular firm has contributed to the agency’s failure to take appropriate actions against it.

One impact of such capture has been weak enforcement. While the SEC can take companies to court, extract civil penalties and bring contempt charges for repeat violations, the agency has only given ‘slaps on the wrist’ to those firms involved in the financial crisis. Instead, it has preferred to settle out of court with big banks. These settlements allow banks to merely pledge to desist from breaching antifraud laws again and pay penalties—which are typically not very onerous considering the bank’s breach and benefits they derived—without ever having to admit to any wrongdoing.

Following Judge Rakoff’s ruling, the SEC defended its practice of settling out of court by arguing that settlements deter future bad behavior because they make firms pledge to improve business practices and impose monetary penalties. The agency suggested that were it required to extract an admission of guilt, more institutions would take cases to court. This would tie up limited SEC resources and force the regulator to pursue fewer cases. This line of defense relies on two flawed assumptions – first, that current settlements deter future violations and, second, that a lower caseload would weaken incentives to comply with regulations.

Firms will opt to fully abide by the law (or not) depending on economic incentives – i.e. whether the benefits of abiding by the law significantly outweigh the costs. Currently, the costs imposed by the SEC are low. Pledges are virtually costless, and the penalties imposed by the SEC are small relative to the profits of these large institutions and the benefits they derive from improper behavior. Furthermore, the SEC has shied away from closely monitoring the banks’ compliance progress, and has done little to impose high penalties for failure to comply with pledges made.

Citigroup is a prime example. It is accused of negligence in the loss of $700 million of investor money, and agreed to pay $285 million, which is less than eight percent of the bank’s profits in just the third-quarter of 2011 alone. Moreover, because these settlements do not require companies to admit guilt, the bank is further shielded from investors taking them to civil court, and the Justice Department is in less of a position to press criminal charges against executives.

A New York Times analysis found that over the past 15 years, at least 51 cases have involved recidivism by 19 Wall Street firms. In many of these cases, the SEC could bring contempt of court charges, but it has not done so in at least 10 years. Most major banks are repeat violators. Bank of America, for instance, has four violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and four for purposeful fraud by securities firms since 1998. During the same period, Citigroup amassed five violations for purposeful or negligent fraud in interstate commerce, and three violations for purposeful fraud by securities firms. None of these past cases were even mentioned in the SEC’s charges against Citigroup in the case before Judge Rakoff, and no contempt of court charges have been made against the bank.

Finally, the SEC should be in a position to welcome a somewhat lower caseload if the cases it more forcefully pursues do substantially increase the cost of non-compliance. If any corporate firm has a somewhat lower probability of being investigated, but faces a substantially higher cost if probed, it will be far less likely to violate regulations because the expected costs associated with illicit behavior increases. Increased costs, in the form of higher penalties, investor lawsuits and possible jail time for executives, would serve as a strong deterrent. Currently, no executives have been successfully prosecuted for actions leading up to the financial crisis. This is in sharp contrast to the aftermath of the Savings and Loan (S&L) crisis of the 1990s when more than 1,100 cases were sent to the Department of Justice for prosecution, resulting in 800 bank officials going to jail.

Taking on very large firms and raising the costs of violating the law are not impossible tasks. It can be done. In fact, in 2008 American and European authorities went after Siemens, a German multinational company, for making large amounts of dubious payments globally. By 2010 Siemens had paid out nearly $3.4 billion in investigations, back taxes and fines to end the probe. Fines to authorities in the United States and Europe cost the firm $1.6 billion. In addition, in German court one senior manager and two executives were found guilty of wrongdoing and were fined and sentenced to probation.

Conclusions and Implications

Focusing only on the minimum needed for the SEC to settle with Citigroup and to satisfy the specific challenge presented by judge Rakoff misses the much larger picture. The judge’s ruling brings to light, once more, the extent to which the regulatory agency may have been subject to capture and undue influence by financial institutions, while also potentially challenging the status quo. Selectively, let us suggest five areas that warrant attention:

- The debate on how to stem the undue influence of big banks should be revisited, and a spectrum of more stringent measures—even including the breakup of the biggest banks—ought to be seriously considered. Revolving door policies should be revisited. Cooling off periods should be extended, especially for persons occupying sensitive positions that are particularly vulnerable to capture.

- The public should debate the implementation and application of regulations by the SEC under Dodd-Frank, focusing on how the bill is faring and codifying the interests and arguments behind the efforts by financial institutions and lobbyists to delay or water down implementation of relevant aspects of the bill.

- The cost of violating securities laws should be increased substantially. Simply raising the monetary out-of-court settlement with no admission of guilt will not alter the incentive structure. Rather, the SEC and others should not avoid contempt of court challenges for recidivist banks. More generally, banks should end up in civil court more frequently; settlements should include admissions of guilt, thus facilitating criminal and civil litigation by wrong parties; and financial settlements with the SEC should be larger by a multiple factor. Congress should also seriously consider the recent request by SEC Chairperson Mary Schapiro to allow the agency to levy larger fines against securities law violators.

- Like Judge Rakoff’s decision, the extent to which all judges exercise their due responsibility by not ignoring unfair out of court settlements that unduly benefit one party to the detriment of the social good and broader systemic risks, should be reviewed and publicized.

- In a transparent and evidence-based manner, an in-depth review should be undertaken to discern whether the Department of Justice has been overly weak in failing to pursue criminal cases against senior bank executives. More generally, there should be increased transparency and disclosure regarding information in the financial sector, including on the Fed’s actions, as well as increased public debate on how campaign finance and lobbying contributions affect voting records in Congress and on politicians’ influence in implementing the regulatory regime and their agencies.

These tougher transparency, regulatory and enforcement incentives would further raise the costs of violating securities laws because companies would face the added risk of investor lawsuits, and possible criminal prosecutions by the Justice Department against executives.

Whether Judge Rakoff’s ruling will set a precedent is unclear, and it depends greatly on the White House, Congress, the SEC, other judges, civil society and reformists in the private sector to seize this opportunity and to address the persistent and costly phenomena of capture.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edJudge Rakoff Challenge to the S.E.C.: Can Regulatory Capture be Reversed?

December 2, 2011