Every so often an academic finding gets into the political bloodstream. A leading example is “The Great Gatsby Curve,” describing an inverse relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility. Born in 2011, the Curve has attracted plaudits and opprobrium in almost equal measure. Over the next couple of weeks, Social Mobility Memos is airing opinions from both sides of the argument (see previous posts

here

).

The Great Gatsby Curve may illuminate an important relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility. (See contrasting views on this question in previous posts in this series). But does it inform policy?

Everybody agrees that the Great Gatsby Curve does not prove a causal relationship. A reduction in inequality—say, in the Gini coefficient—will not necessarily lead to an increase in intergenerational mobility. Rather the relationship provides a way to think about the factors that are driving both inequality and immobility.

Three key factors…

A paper by University of Michigan economist Gary Solon helps us think through the forces that drive both trends and therefore the Great Gatsby Curve itself. The paper lists three major social institutions that affect mobility: the labor market, the family and the state. (Miles Corak has a helpful graphic in a paper for the Center for American Progress.)

1. Jobs

The labor market, unsurprisingly, has important consequences for mobility. In Solon’s model there are two ways mobility and inequality interact here. First, a higher return to education encourages more investment in human capital, i.e. education. But second, increased education costs can reduce investment, by deterring lower-income students. So we need to keep an eye on access to higher education for all students.

2. Families

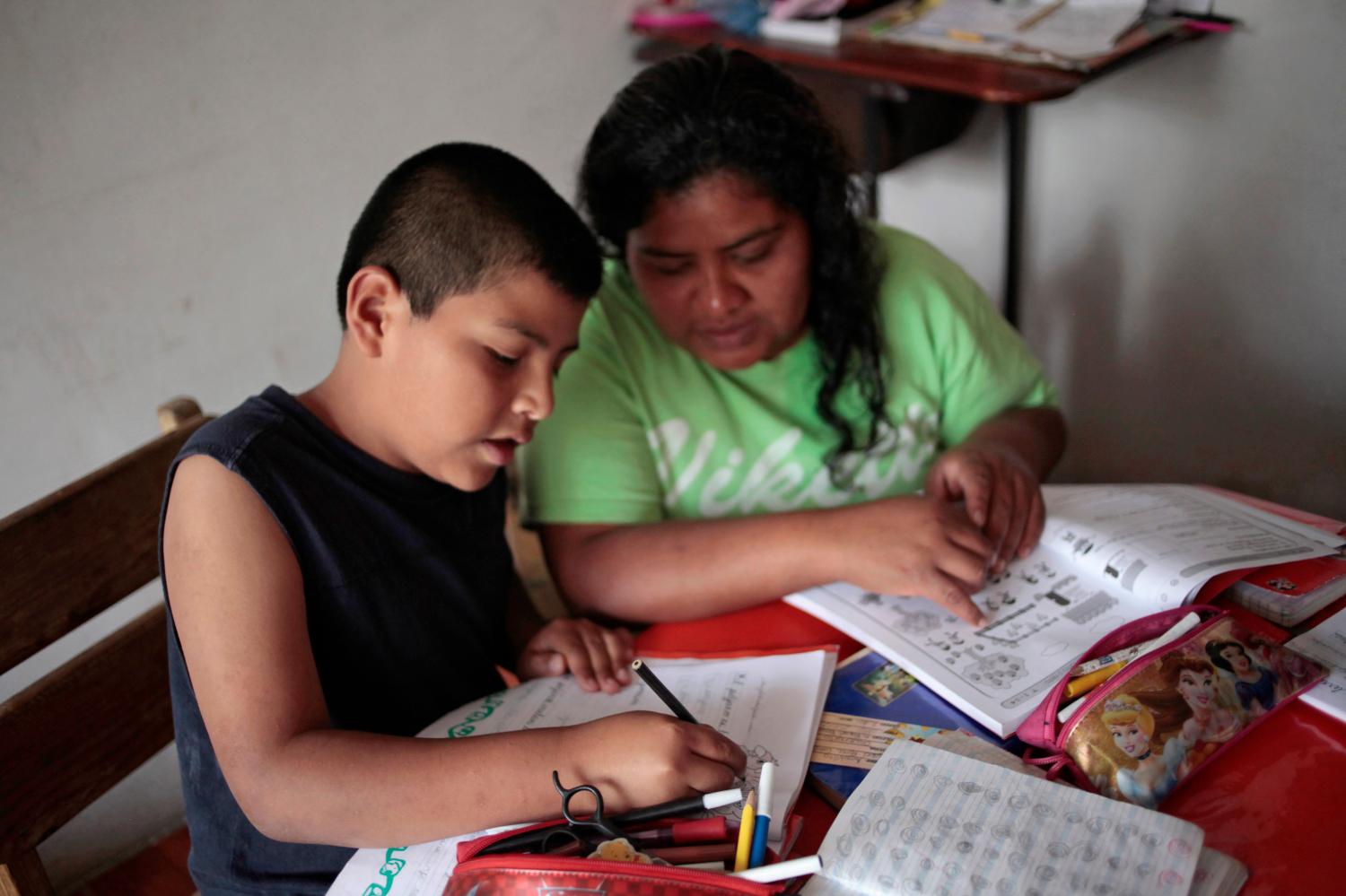

Families with more human capital are more likely to invest in their children, in both time and money. So more inequality of human capital increases the chances that inequality will be passed on to the next generation, resulting in lower mobility.

Job quality also has an impact on parental time with children. Few children today are being raised in a family with a stay-at-home parent. So the care and nurturing of children has to be coordinated with parents’ work schedules. If parents’ jobs have erratic or unpredictable schedules, or schedules that conflict with children’s needs, or fail to offer paid time off to care for a sick child, or leave parents unduly stressed each day, the result is likely to be negative in terms of children’s development and future human capital.

3. The State

Of course there is another actor here: the state. Government policy can boost mobility. Crucially, however, government investments need to be in lower income household in order to improve mobility rates. Take investments in universal pre-K. They would help boost the human capital of young children from lower-income households and help them catch-up to children from higher-income households. Government intervention can also set job quality standards that help families address conflicts between work and family.

From analysis to action

Policy recommendations stemming from the Great Gatsby Curve are largely about leveling the playing field in terms of human capital investments. This may require rethinking not only direct investments in children, but their parents’ jobs as well.

High levels of income inequality may hinder the ability of lower-income children to reach their potential. This means not only a lower level of mobility, but also a slower rate of growth for the overall economy: a fate we all wish to avoid.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Jobs, family, state: Policy implications of the Great Gatsby Curve

May 22, 2015