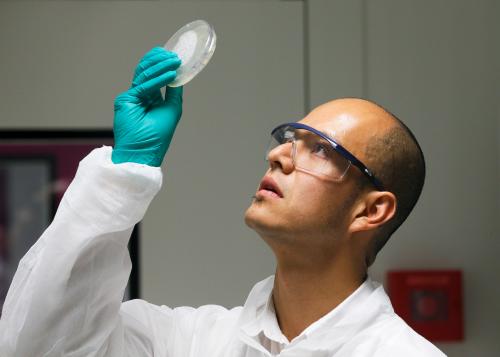

Last fall, when Chinese scientist He Jiankui announced that he had created the world’s first gene-edited babies, he was greeted with widespread condemnation by the scientific community. While some experts called for a moratorium on embryonic gene editing, others sought a different path forward. Meanwhile, clustered regularly interspaced repeats (or CRISPR) has gained significant headway in the past year. Laboratories are racing to optimize its gene-editing capabilities, human gene-editing clinical trials underway, and academia-industry collaborations are paving the path to commercialize CRISPR-based therapeutic treatments. With these developments, it is increasingly important that various stakeholders, scientists, and policymakers resolve the clear ethical, societal, and safety issues posed by gene-editing technologies.

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR is based on bacterial immune systems. Scientists have re-engineered these systems, consisting of a single, target molecule complementary to a gene of interest and a protein known as Cas9, to make precise cuts in the genome. CRISPR gene editing enables scientists to locate and remove harmful genetic sequences and replace them with either neutral or beneficial genetic material. CRISPR provides a relatively versatile, cost-effective platform to treat debilitating genetic diseases such as Sickle Cell Anemia and Cystic Fibrosis, create gene drives that spread or suppress certain genes to reduce disease transmission chains, and inspire innovation in the design of high-yield, disease tolerant crops.

Gene editing regulations in the U.S. and abroad

Although the U.S. has no outright ban on editing the genes of human embryos, a restrictive regulatory landscape and a lack of federal support has imposed significant restrictions on researchers. Earlier this year, House Democrats reluctantly restored a rider to a 2020 spending bill that bars the FDA from considering requests to approve any clinical trial “in which a human embryo is intentionally created or modified to include a heritable genetic modification.” Additionally, Congress has banned NIH funding for research involving live human embryos, forcing researchers to either abandon these projects entirely or seek private funding with fewer restrictions.

Additionally, a patchwork of international regulations further impede attempts at creating a comprehensive framework for regulating CRISPR and other gene editing technologies. While Sweden, Belgium, and the UK allow the creation of human embryos for research purposes, the complex regulatory landscape is murkier in other countries, comprising of legally binding bans, ambiguous rules, or unenforceable guidelines.

Considering future generations

Researchers have long struggled to draw a line around ethical genome editing. While modifications to somatic cells only affect a single individual, engineering germline cells (such as eggs, sperm, or embryos) ensures that a specific trait will be transmitted to future generations. Although many scientists contend that somatic genome editing could dramatically advance human health, the ethics of germline modification remain controversial.

Worries of the ethical implications of deliberately editing out entire traits and concerns over the destruction of human embryos for research purposes have stigmatized germline genome editing. Moreover, the threat of unintended consequences and “off-target” effects emphasize the risk posed by CRISPR-driven research on germline cells and human embryos. But over the past decade, advances in research methods and laboratory techniques and an increased understanding of the human genome have attracted greater attention to the therapeutic potential of CRISPR gene editing.

Is there a responsible way forward?

Shortly after the 2018 International Summit on Human Genome Editing, organizers of the summit published an editorial in Science Magazine moving the discussion from whether to proceed with heritable modification towards how best to do so. International academies provide a great platform to convene experts and stakeholders to inform the development of criteria and standards to which genome editing in human embryos must conform.

However, as the authors of the editorial note, any criteria require enforcement mechanisms long after their development. A future framework should appropriately address how researchers can raise concerns about experiments that fail to conform to accepted standards, the various governance options in enforcing these standards, and whether it is possible or even desirable to streamline the accountability process. The authors suggest the creation of an international registry of planned and ongoing experiments as a potential accountability measure.

Since a robust understanding of the science behind CRISPR must still be developed, the most important responsibility that scientists have is to educate, engage, and empower the public and policymakers. Only then will all stakeholders be able to take part in discussions about the ethics of heritable genome editing and resolve the complex ethical issues surrounding CRISPR.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is there a responsible way forward for gene editing?

October 29, 2019