In response to the rising prominence of artificial intelligence and after years of investment in digitalization, Germany has taken new steps to institutionalize governmental data analysis. A €239 million investment is building data labs in every ministry and the Chancellery, adding new capacity across the federal government. To succeed, these data labs must be integrated into an already network of ministry data teams, statistical offices, technical services agencies, and government-funded research institutes, raising questions about to best organize the various roles of data analysis in a complex government bureaucracy. This paper presents the first comprehensive overview of the state of governmental data analysis in Germany, offers an assessment of how these data labs can best be used, and provides recommendations for how Germany can further develop its data-driven capabilities.

Compared with other wealthy nations, Germany performs below average on international rankings of digitalization and it has been fairly criticized for insufficient progress, despite billions of euros in spending. However, specifically concerning governmental data analysis (a subset of digitalization), the reality is more complex, with Germany lagging in some areas and leading in others. Germany has well-established resources for policy microsimulation and forecasting, making it a leading nation in anticipatory governance. Although historically underutilized, Germany has effective and increasingly formalized approaches to data-driven program evaluation. A few long-standing offices conduct surveys and provide official statistics, although these agencies are highly centralized, and many ministries are struggling with requirements to open data and build data-driven services. Outside of government, data analysis is buoyed by a robust academic environment and growing private sector, offering opportunities to the government to learn and bring in expert talent.

Deploying the new data labs with an intentional focus on operational tasks in the federal ministries will make the best use of these resources and help address current shortcomings. To start, the labs should work to ensure the many new data streams from digitalization efforts will be usable for analytical purposes. Because they are placed within the various ministries, these labs are better positioned to develop expertise in implementing algorithmic processes, as compared to other centralized technical agencies. Their placement also uniquely enables the data labs to develop data-data culture and provide domain-specific training on using data within their respective ministries. Finally, the Chancellery’s data lab is best suited to helping the ministry labs overcome shared bureaucratic burdens and playing a coordinating role in emergency situations to enable rapid cross-governmental data analyses.

Even with this important new investment in data capacity, there are other steps Germany can take to better institutionalize governmental data analysis:

- Install chief evaluation officers in each ministry’s leadership to better incorporate data-driven evidence into everyday policymaking.

- Create new pathways for data scientists to enter government to prepare Germany for its long-term talent needs.

- Seek to better understand its capacities by surveying government employees on their use of data and considering the evolving data needs of regulators.

- Develop a comprehensive government plan that delineates between the roles of the technology authorities to create accountability and prevent duplication of efforts.

introduction

The German government has a history of data analysis that extends back even before Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III, who created the Royal Prussian Statistical Bureau in 1805.1 Yet recent trends, especially the huge investment in digital services2 and the rising prominence of artificial intelligence (AI), have heightened interest in how data can improve governance. In January 2021, the Federal Data Strategy called for all federal ministries to hire a Chief Data Scientist.3 Shortly thereafter, the German Recovery and Resilience Plan reiterated this requirement and allocated €239 million to establish a data lab in every ministry and the Chancellery.4 These investments are intended to build on top of the multi-billion euro investment in digitalizing government services,5 and beyond its own borders, Germany has placed itself at the center of Europe’s digitalization efforts through the 2020 Berlin Declaration on Digital Society.6

This renewed focus on data will likely persist into Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s new government—the first section of the new Chancellor’s coalition agreement is entitled “Modern State, Digital Awakening and Innovation,” and calls for federal administration not only to become more digital, but also more proactive in supporting citizens.7 Clearly, there are changes to come, as evinced by the expanded scope of technology issues given to the newly renamed Ministry for Digital Affairs and Transportation.8 Despite these new responsibilities, government digitalization is fairly dispersed, with important roles for the Ministries for Interior, Finance, Education and Research, Economic Affairs and Climate Action, International Development, and Foreign Affairs. As for the Chancellery, it seems that Chancellor Scholz may have less interest in leading these efforts than his predecessor, Angela Merkel.9

“Data analysis is becoming ever more important to core functions of governance, both through existing mechanisms, such as official statistics and program evaluation, but also more recent developments such as algorithmic processes.”

Regardless of who leads these efforts, the German government should work to develop a comprehensive and long-term vision for effective public sector data use. Data analysis is becoming ever more important to core functions of governance, both through existing mechanisms, such as official statistics and program evaluation, but also more recent developments such as algorithmic processes. The rapid advance of private sector applications of data also poses a challenge, creating a stark contrast to antiquated government services that can undermine trust in public institutions, and further challenges governments to learn and adapt data science methods for regulating the private sector.

These trends are evident today, and so governmental capacity for data analysis should be considered a foundational pillar of modernizing Germany’s public administration.

data Analysis capacity in german federal governance

Understanding the current state of data and digitalization in the German public sector is a prerequisite for effectively deploying new resources—such as the data labs—and identifying what other steps Germany should take. A recent report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) categorizes the value of data to governance into three broad activities: (1) anticipation and planning; (2) service delivery; and (3) evaluation and monitoring.10 These categories offer a useful starting point for the German context, where digitalization and new algorithmic processes are changing service delivery. Anticipatory governance has seen recent changes too, with new approaches to microsimulation and an increased interest in forecasting. Further, Germany has established systems for monitoring through program evaluation, official statistics, and open data, although many challenges remain. Still, it is important to go beyond the OECD’s framing, and consider a fourth category of (4) related non-governmental factors, especially civil society, academia, and the private sector. The four-part typology is undoubtedly flawed[i] and omits many important topics,[ii] but it provides a useful framework to broadly divide how the German government is using data analysis.

(1) Anticipatory Governance

Anticipatory governance is the use of data to better forecast the future state of policy-relevant information (usually with statistical forecasting models) and more rigorously estimate the effect of policy changes (usually with microsimulation models). The German government funds a range of sophisticated microsimulation models for analyzing potential policy changes that are maintained by independent research firms and academics. This includes MikroSim, a novel and complex effort to simulate each of Germany’s more than 10,000 municipalities for population dynamics, education, and income, using synthetic population data.11 Other examples include tax and transfer models from at least five institutes,12 as well as Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research’s corporate taxation model,13 and an old-age insurance model from the Fraunhofer Institute.14 Beyond the policy planning value of these models, they also demonstrate the capacity of German policy research institutes to develop large and resource-intensive data-driven modeling systems.

Several German policy institutions also work on statistical forecasting models that are used to make predictions about the likely outcome of future trends and are considered valuable for anticipatory governance. Economic forecasts are the most common, including estimates of GDP, inflation, employment, and even sectoral-specific metrics.1516 The Joint Economic Forecast, a collaboration between five independent research institutes, pools data-driven predictions for a biannual report to guide economic policy.17 Environmental models, such as those for measuring flood risk, are also used to inform emergency preparedness.18 In response to the recent prominence of immigration issues, various research institutes1920 and the Federal Office of Migration and Refugees21 are also making attempts to forecast future migration demand into Germany. The Federal Foreign Office’s PREVIEW is an attempt to build a crisis early warning system which started in 2017.22 Overall, these anticipatory government efforts are well-developed, although much of the capacity for this type of data analysis lies outside the federal government.

(2) Data-driven service delivery

Germany’s enormous investments in government digitalization, led by the Interior Ministry,23 is significantly increasing the amount of data and data infrastructure across the government. The Online Access Act and subsequent decisions will allocate over €5 billion to digitize nearly 600 different types of government services, affecting all 15 federal ministries, as well as 16 state and over 11,000 local governments.24 However, as of mid-2021, only 54 services were available online. [iii] A federal advisory agency, the National Regulatory Control Council (NKR), has determined that, despite recent momentum, the program will not meet its target deadline of the end of 2022.25 Still, these extensive digitalization efforts promise to create many new streams of data and additional technical infrastructure that could provide significant opportunities for future data analytics and algorithmic processes.

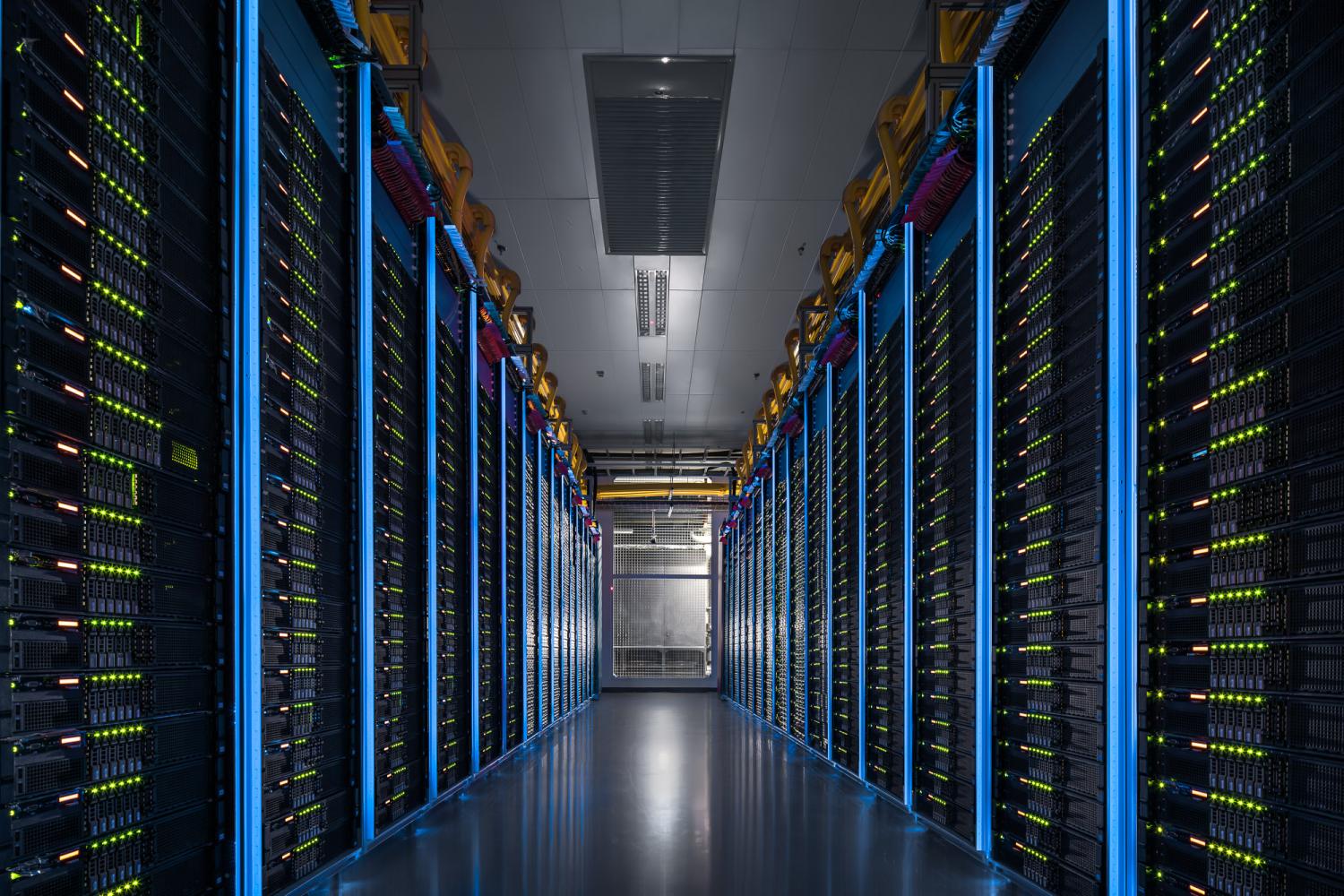

Several authorities are supporting the government digitalization and are relevant to the state of data analysis—especially ITZBund and Digital Service 4 Germany. Starting in 2015, disparate federal IT capacities have been integrated into a consolidated federal office, ITZBund,26 including the Bundescloud, a new national cloud service. This Bundescloud offers several basic cloud services,27 including a software development platform that could be used for data science applications.28 This is part of Germany’s “multi-cloud approach,”29 which aims to both encourage private providers to offer cloud services using data centers in Germany,3031 and develop its own internal government cloud capacity.32 Digital Service 4 Germany is a notable technical services agency housed in the Chancellery,33 akin to the United States Digital Service. Although Digital Services 4 Germany is more focused on digitalization and software development, its work will often overlap with data analysis and data science applications.

Germany is also seeking to reduce administrative burdens on users of government services, the purpose behind the Register Modernization Act of 2020. This law seeks to advance the “once-only principle,” meaning users of government services are only asked to supply a data point once, not multiple times by different forms or ministries.34 Reducing administration burdens, as required by the European Union’s (EU) Single Digital Gateway Regulation,35 is the primary goal, but this regulation has the added value of necessitating interoperability and a common identifier between various ministry databases—furthering the databases’ value for data analytic purposes. The most prominent example is that this integration can more easily enable the counting of the German population, which does not conduct a survey-based census.36 Recently, the NKR said the register modernization effort was “still in its infancy.”37

Beyond simply replacing paper with electronic forms, ministries have begun to expand the use of algorithms in government processes formerly performed by people. One example is the Ministry of Labor’s newly-automated analysis of forms required for government child support payments.38 While document processing is relatively commonplace in government, more ambitious projects are also in the works, such as the Ministry for Digital Affairs and Transportation’s trial project to automate highway damage monitoring.39 A recent report on the use of AI in public authorities documents these and ten other cases studies, but also notes that governments needs more data analytics talent, as well as better standards for the use of algorithms in government.40 A survey of federal ministries by the Ministry of Education and Research publicly documented 79 deployed AI systems41 and 190 further pilot and research projects,42 although the information is sparse. Of the deployed systems, almost none had gone through any algorithmic risk assessment, and several ministries seemed not to even understand the concept of an algorithmic risk assessment.43 Of the 79 documented AI systems, 35 were developed internally by ministries and 35 were externally developed by private companies or universities. ITZBund is involved in developing the remaining nine AI services for other ministries, including the Ministry of Finance, the Customs Investigation Bureau, the Federal Tax Office, and the Financial Intelligence Unit.44

(3) Monitoring and evaluation

Germany has a mature program of official statistics, largely run by a few independent federal authorities with deep expertise, especially the Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Destatis),45 the Institute for Employment Research,46 and the Robert Koch Institute (RKI).47 Destatis is the principal data owner, and has its own extensive digitalization plan that aims to bring together its own survey data, ministry registry data, and external experimental data collections.48 All these authorities are experimenting with emerging data science approaches, such as IER using digital trace data for labor market measures,49 Destatis using mobile phone data to see effects of COVID restrictions on mobility,50 and RKI making use of citizen’s data donations.51 While Germany displays mature capacities in official statistics, the federal statistical functions are relatively centralized in these few authorities[iv] and are progressively more directed by E.U. requirements.52

Data-driven program evaluation remains among the most critical contributions of governmental data use,53 but its use in Germany has been only recently, and partially, systematized. In 2013, an effort started to create a systematic evaluation procedure for all laws and regulations estimated to have over €1 million in compliance costs,54 but otherwise, there is no federal or state law requiring program evaluation.55 Despite no universal standard, it has become increasingly common for laws to include clauses that require an ex-post evaluation some years after the law’s implementation.

While the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development has had an evaluation unit since 197156 as well as an associated institute,57 this is the exception, not the norm. Evaluations are frequent in some other policy fields, especially in labor policy,5859 social programs, and higher education.60 The government leans heavily on the economic and social science research institutes in the Leibniz Association and Fraunhofer Society, as well as private contractors61 to perform this work.62 This may reflect a somewhat recent change, as, at the prompting of the German Research Council, many of the Leibniz Association institutes made significant investments in evidence-based policy during the 2000s.63 External institutes are generally able to work with the government administrative data necessary to perform these ex-post evaluations. Despite starting later relative to its peer countries, Germany has quickly developed an expansive system of researcher access to sensitive administrative data.64 The German Data Forum now has accredited 38 research data centers that offer access to this confidential governmental data,65 more than the United States’ 31.66

In June 2021, the Bundestag adopted the Second Open Data Act and the Data Usage Act, expanding its commitment to publicly releasing machine-readable data.67 In 2019, two years after the passing of the first open data act, 75% of agencies had an open data officer, but 57% of agencies said there was insufficient staffing for their legal obligations.68 Still, there are currently tens of thousands of datasets on GovData.de centralized data portal, and while the amount of data contributed varies dramatically between federal ministries,69 most will be required to open up data by 2023 under the new open data strategy.70 This also requires an expansion of the number of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for government data by 2024, building on the 30 that are available now.71 Beyond broadening public access to data, the new coalition agreement calls for a new data institute that would help open government data in order to fuel new business models and social innovations.72

A final governmental factor is the receptiveness of policymakers to data and evidence, or the culture of evidence-based policymaking. A 2011 expert survey of 19 OECD countries assigned Germany the 2nd lowest score for the use of program evaluations in government.73 This is a concerning rank, but it is based on the presence or absence of formal arrangements for disseminating evaluations to policymakers, and thus does not measure the culture or tendencies of policymakers using evidence. Regardless, there have been signs of progress in the last decade. The Bundestag has also not historically been especially invested in commissioning or using evaluations, but references to empirical evaluations in Bundestag materials nearly quintupled (568 to 2451) from the 15th Bundestag (2002-2005) to the 18th Bundestag (2013-2017).74 Several organizations are also working to improve the culture of evidence, including the German Economic Association, which released principles for better evidence-based policymaking,75 and the Halle Institute, which founded a Centre for Evidence-based Policy Advice.76 In 2021, the Federal Academy for Public Administration launched the Digital Academy77 to train public servants in digital skills, including data literacy.78 These developments reflect a growing appreciation that the value of government data is not automatic, but must be understood and consciously integrated into policymaking.

(4) Non-governmental factors: Civil society, academia, and the private sector

There are several external factors that will significantly affect the government’s ability to make advances on data use. This includes academic programs as key pipelines of new data talent and independent civil society organizations that can drive new data science applications. Further, the general perspective and opinion of German citizens matters, as politics impacts what is possible for government data.

Nonprofit organizations have begun to develop lines of data science work that complement government efforts. The nonprofits Correlaid, DatenSchule, Data Science for Social Good-Berlin, and Code for Germany offer partnerships and trainings to help bring data expertise into social good organizations. Other organizations have recently started to build data capacity for studying societal problems, including the think tank Stiftung Neue Verantwortung79 and the Bertelsmann Foundation.80 The German government is also supporting some civil society experimentation with AI through small (€20,000) grants awarded by the new Civic Innovation Platform.81

Academia also plays a key role, both by creating pipelines of new talent for civil service and performing informative research. There is an emerging cohort of master’s programs that specifically focus on data and governance. These include programs focused on applied data science and how it overlaps with policy, as in the Hertie School’s M.S. in Data Science for Public Policy,82 or social science, as in the University of Konstanz’s MSc in Social and Economic Data Science.83 Mannheim University’s new Master of Applied Data Science and Measurement has a unique emphasis on the challenges of data collection, particularly useful in governance.84 Also notable is Friedrich-Alexander University, which is one of the partner institutions in the new E.U.-funded Master of AI for Public Services.85 More broadly than policy and social science, Germany leads the EU in specialized AI academic programs.86

The academic research community in data analytics, AI, and related fields is also quite strong. Germany ranks around fifth or sixth in a number of AI publications, depending on the precise metric used.87 To improve further, the National AI Strategy called for 100 new AI professorships, and various efforts such as those by the state of Bavaria88 and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation may help Germany exceed this goal.89 Especially valuable to governance are the programs that focus on the overlap between data science and social sciences, such as those mentioned above.

The private sector, whose skills and expertise can be harnessed and exchanged with the federal government, is also a strength for Germany. Looking at both academia and the private sector, Germany has the most researchers working in science and technology in the EU.90 In terms of talent, Germany’s private sector ranks 6th in both investment in AI and in AI hiring. Further, Germany ranks 4th among 13 leading countries in AI skill prevalence (27% higher than the global average) and is especially strong in the industries of Hardware, as well as Networking and Manufacturing.91 However, according to the European Investment Bank, Germany lags behind both the United States and the EU average in the digitalization of other private industries, including construction, services, and infrastructure.92

Finally, as in any democracy, the perspective and the trust of the German people are key factors in its government’s continued ability to use data. One approach is to consider the extent to which German citizens use digital services, although these numbers vary: the EU’s Digital Economy and Society Index reported that in 2020, 69% of citizens in the past year had used a digital government service.93 However, a report from the German government says that only 40% of citizens submitted a form or application to the government online in the past year.94 This disparity may reflect that German citizens would prefer to use online government services, but are stymied by the common requirement of paper form submissions with handwritten signatures.95 The same report found that 40.7% of Germans saw AI as an asset, compared to 26.5% who saw it as a threat—these numbers coming before the government of neighboring Netherlands had to resign over an algorithm that erroneously punished families for benefits fraud.9697 A 2014 poll found that the German people were especially concerned with data privacy, with 80% being reluctant to share data with businesses.98 However, Germans showed more trust in their government in a 2018 survey, with just over 40 percent expressing concerns about data security in online public services.99

Summary and international framing

Overall, these factors describe a mature governmental use of data, with Germany lagging other wealthy nations in several areas and leading in a few. There are a few international rankings from the EU, UN, and OECD that warrant consideration, although they tend to focus more on law and procedure and less on harder-to-measure ‘on-the-ground’ factors that might be more informative. The European Commission’s (EC’s) Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) estimates that Germany’s digital public services are about average among EU members.100 This top-level estimate masks significant variation within the sub-indicators, as Germany ranks 8th in open data, 10th in e-Government users, 12th in digital public services for businesses, 16th in digital public services for citizens, and 23rd in pre-filled forms (which is a useful proxy for how interconnected ministry databases are).101

The OECD’s Digital Government Index is more critical, putting Germany third to last in its ranking of “data-driven public sector.” However, this analysis was last performed in 2019, and counts against Germany several points that have since been rectified, including the lack of a public sector data policy, no plan for intragovernmental data sharing, and no requirement of chief data officers.102 The United Nations E-Government Survey scored Germany as in middle country among 33 European nations evaluated. Despite a strong showing on Germany’s human capital development, the UN scored Germany poorly on the government digital services—an analysis that aligns with that of the EC’s DESI.103

Germany’s capacities in microsimulation models and independent researcher access to government administrative data are areas in which the country leads. The academic environment is also relatively strong, both in AI research generally, and specifically in emerging pipelines of public-sector technical talent. This is critical because having an expansive talent pool makes it far easier to rectify other capacity issues in the short term. More broadly, however, non-governmental civil society efforts are nascent and appear to be trying to catch up to current practices, rather than innovating and leading.

Policy and operational recommendations

This section discusses the additional steps to improve Germany’s public sector data capacities, but it is first worth discussing what should be done with changes already in progress—specifically, the new ministry data labs, the Chancellery’s data lab, and the Data Service Center. The data labs are best placed to use data to directly support the operational work of ministries through developing data pipelines, implementing algorithmic services, and fostering an analytical culture. The Chancellery data lab is better suited for a coordinating role, especially for emergencies, as well as enabling the ministry labs to overcome bureaucratic challenges. Finally, the new Data Service Center can handle especially difficult technical challenges that are shared across the data labs and other centers of data analysis.

Beyond establishing these offices, Germany should consider a range of other policies to improve its capacity for, and use of, data analysis. To improve the internal capacity and the culture of evidence-based policy, Germany should require and fund a chief evaluation officer in every ministry and consider other new entry points for technical talent. To better learn about the current state of capacity, Germany should employ surveys of government employees on these topics, and especially consider the evolving role of regulatory data science, which has so far been under-discussed. The federal government should also develop a central strategy and organizational chart that clearly defines the roles of the many public agencies with data analytics responsibilities. Finally, there are further steps that can be taken to strengthen data science in relevant civil society organizations.

Ministry data labs should focus on operational data science

The newly-installed or incoming chief data scientists and their data labs should focus on the tasks that benefit most from using internal data talent and also address Germany’s deficiencies in institutional data. Broadly, the data tasks that meet both of these criteria are operational, in that they directly support day-to-day ministerial function, as opposed to data-driven evaluations or anticipatory governance. Of course, the needs of different ministries will vary, but generally, data labs should give special priority to the following operational tasks:

- Ensuring data from digitalization is analytically usable: The enormous effort by German ministries, states, and localities to digitize their public services does not guarantee that the resulting data will be useful for analytical purposes. Data labs can and should play a key role by being an advocate for effective collection, documentation, and storage of digital services data so that it is valuable for other purposes. Given the rapid pace and enormous scale of the digitalization efforts, this is likely a time-consuming, but highly important, line of work. This work aligns well with a task explicitly handed to the data labs by the Recovery Plan, which is to build a nationwide Data Atlas.104 As the data labs better document their own databases, they should also collaborate to build this cross-ministerial overview of all federal government data.

- Building data-driven culture and capacity: Data labs can also work to enable broader data access and use within their ministry. This might mean helping employees get database access where ministry employees can themselves perform data analysis, or through dashboards, where data has been preprocessed and visualized for them. One model for this work is the U.S. Commerce Department’s Data Academy, which in 2016 and 2017 put on a series of trainings105 for over 1,600 departmental staff to improve their data analytics capacity.106 The Commerce data team also used these trainings to identify strong candidates for more advanced data education, helping create new centers of expertise across the department. In doing trainings, the ministry data labs should be careful not to build duplicative content with that of the National Digital Academy, which already has at least one course on data literacy.107 The data labs should instead go deeper into ministerial-specific data and how it can inform the day-to-day work of ministry staff. The data labs will be uniquely positioned to do this because of their proximity to operational employees and expertise working with ministry-specific data.

- Data-driven and algorithmic processes: Due to their proximity to the front lines of government service delivery, the new data labs can work to identify existing processes that would most benefit from automation and algorithms. This can help address the relatively poor performance of Germany’s digital public services, as well as the shortage of AI talent as reported in the aforementioned AI in public authorities report. To be most successful, the new data labs should generally work to improve upon workflows that ministries are already doing rather than attempting to build entirely new processes. While improving the function of government should be the core goal of the data labs, there is some evidence that these investments in analytics can also save significant funds by reducing fraud and waste.108

- Institutionalize new data pipelines: The data labs are well-positioned to build new data collection pipelines, bringing novel external data into governance. The authorities with established data capacities already do some of this work (i.e., Destatis, RKI, and IER, as mentioned in the monitoring and evaluation section), but most do not. Where possible, ministry data labs should build on successful proof-of-concepts from academia and civil society, and use the consistency of government funding to productionize (or make permanent and sustainable) the data pipelines. Ideally, these new data collections would both inform ministry function and be released to the public as open data.

These priorities are core functions of governance and would be an investment in the areas that German governance needs most. Reflecting this, the data labs should also strive to build internal capacity, while minimizing procurement or outsourcing. One reason the data labs are so valuable is they can offer routine interaction between ministerial staff and data analysis expertise, which is where the operational value of data analysis is realized. Further, data analysis is a core and structural function of government, not the short-term projects or insulated deliverables that are suitable for consulting or contracting. This means the procured software and solutions are likely to be permanent costs, risking vendor lock-in while losing internal capacity and undermining data-driven culture.109 The data labs should keep as much funding internally as possible, using open-source software and creating new tools that government can iterate and improve on over time.

“One reason the data labs are so valuable is they can offer routine interaction between ministerial staff and data analysis expertise, which is where the operational value of data analysis is realized.”

While these operational tasks should be done in-house, not all data analyses need to be performed internally, and this roadmap for the data labs intentionally prioritizes a few tasks and leaves others out. For instance, the performance of program evaluation is not best served by the data labs, as this can continue to be done by independent research organizations. Program evaluations are a lengthy and complex type of data analysis that often takes months or years, and so an independent institute can perform and deliver results intermittently. Further, it is an advantage to have program evaluation done by independent research organizations that may be less prone to political influence when reporting their findings. This is also true for microsimulation and forecasting tasks, in contrast to operational data analysis and algorithmic systems in the federal government where outside research institutes would be less effective. Otherwise, procurement should largely be used for either general-purpose software and tasks that are common in both government and private sector, or for highly specialized projects that government cannot reasonably be expected to do.

Similarly, the continued development of APIs is also not an ideal goal for data labs, although they may contribute to the process by cleaning and preparing data. This task is better categorized as data engineering than data analysis, and while it requires a specific set of technical skills, its execution is less specific to the domain knowledge. This means that a single entity, for instance the Digital Services 4 Germany or ITZBund, could develop expertise in API development and perform this task across the ministries, rather than having each data lab learn to build high-quality APIs. More broadly, it may prevent duplicative work and prevent conflict if Digital Services 4 Germany, ITZBund, and other technical agencies generally leave data analytic work that requires domain knowledge and routine interaction with ministry staff to the ministry data labs.

The Chancellery’s data lab as coordinator and enabler

The strategic location of the new data lab within the Chancellor’s office, without a specific ministerial function to support and so close to the highest levels of policymaking, warrants a different approach. The Chancellor’s data lab should invest in the capacity to perform rapid cross-governmental data analyses to respond to emergency situations. This approach was pioneered by the New York City Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA), where the team practiced “data drills” to better execute the interdepartmental integration of data sets.110 MODA developed this approach after the office encountered difficulties combining datasets in an (ultimately successful) effort to use data science to help respond to the 2015 outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease in New York City.111 Similarly, due to its location within the White House, the United States Digital Service has also been known to work on high-pressure interagency data and technology problems. By using its centrality and political authority, the Chancellery data lab can bring together data experts from across government ministries, quickly break down barriers, and deliver emergency data services.

This work would also help the Chancellor’s data lab identify barriers to collaboration, which aligns well with a second stream of pertinent work: coordinating and advocating for the structural and bureaucratic changes necessary to support the ministerial data labs. This portfolio might also include enabling the use of open-source programming languages for data science, such as R and Python,[v] or expanding access to collaborative development software such as git. It could also include ensuring that ministry data labs can hire data science talent with appropriate titles and pay scales, which is called for by the Federal Data Strategy and has been done for other IT specialists.112 It may also be worth ensuring that funding streams are consistent and flexible enough such that ministries have a real choice between hiring permanent staff and using procurement.

The importance of these bureaucratic changes should not be downplayed. The needs of civic technology and data analysis in the United States has led to fundamental changes, including smaller and faster procurement (called modular contracting113), new job titles,114 and may even result in a dramatically improved federal hiring process.115 This is a sufficiently critical line of work to warrant making permanent the head of the Chancellery data lab and creating the title of Chief Data Scientist (or Officer) of the federal government, a role that has existed in the United States since 2015.116

The Data Service Center can provide technical expertise

The Federal Data Strategy also calls for the creation of a new office, the Data Service Center (DSC), for cooperating around data use and evidence-based evaluation. While the Chancellery’s data lab should take the lead on bureaucratic challenges to data use, the DSC can instead tackle technical challenges that are shared across the data labs. This might include specializing in providing guidance and support for challenging data-specific tasks related to open data, cloud-based analysis, and algorithmic services.

The DSC may be especially valuable in helping develop best practices for the expanding number of algorithmic services being built by federal ministries. For instance, this includes collaborating across ministries and data labs to create standardized reporting, as in the UK,117 as well as a public registry of algorithms, as has been implemented by both Amsterdam and Helsinki,118 and is in progress in the United States.119 This registry can build on the survey by the Ministry of Education and Research, but should be formalized, placed on a public website, given substantially more detail, and updated regularly.

“The DSC may be especially valuable in helping develop best practices for the expanding number of algorithmic services being built by federal ministries.”

Further, ministries should assess the potential level of harm and develop formalized processes for minimizing that risk, such as benchmarking the algorithm’s performance to an ongoing human comparison.120 Canada’s algorithmic impact assessment tool121 and the Ada Lovelace Institute’s algorithmic impact assessment case study122 are both potential models for this work.

Drawing precise boundaries between the DSC and other existing agencies may be challenging and should be done carefully. For instance, the DSC might provide best practices for the process of opening up government data, such as for data cleaning, anonymization processes, and stakeholder engagement. However, hosting the open data should still be left to the

Ministry of Interior’s GovData.de platform team and the DSC may not be best suited to support API development, since this is a separate set of specialized skills more similar to web development, for which expertise may already exist in technology agencies like Digital Service 4 Germany or ITZBund. Similarly, while the DSC should not replicate ITZBund’s effort to create cloud services, it could instead develop expertise in interoperable data analysis tools to aid various data teams to work effectively with the multi-cloud strategy.

Other recommendations and lessons from the United States

Starting under the Obama administration, the United States renewed a focus on civic technology and data science which has since produced significant progress, although with noteworthy missteps. These efforts illustrate several possibilities for Germany to improve other aspects of data-driven governance, beyond those discussed above.

- Install chief evaluation officers—To further improve the institutionalization of evidence-based policymaking, Germany should consider adding a chief evaluation officer to every federal ministry. Evaluation officers look to actively incorporate existing empirical evidence (from government and external sources) into everyday policymaking. This is distinct from the data labs and chief data scientists in that evaluation officers are only reviewing and synthesizing evidence for imminent policy choices. Since ministries are strong pillars of federal policymaking and are hierarchical in nature, placing evaluation officers directly subordinate to the Minister (in the Leitungsbereich) could be highly impactful. Evaluation officers might also review ministry functions to identify necessary evaluations and build further infrastructure to improve their quality.123 These officers could also further formalize the role of evaluation in the ministries, both by documenting the current state of evaluation use, and by writing an official policy detailing the circumstances in which the ministry performs program evaluations.124

- Create new government talent pathways—Germany has an aging public workforce, with the proportion of government employees aged 18-34 falling from 30% in 2020 to 15% in 2015.125 Beyond the employees and trainings of the data labs, policymakers should also look to enable new pathways for data science talent. For instance, the Chancellery could build on the success of the tech4Germany fellowship, which brings technologists into the federal government for three-month sprints,126 to include data science projects. Developing a program analogous to the U.S.’s Civic Digital Fellowship, which attracts technically talented students to government internships, is another option.127 Lastly, Germany should consider creating a Chancellery Innovation Fellowship, analogous to the Presidential Innovation Fellowship, and using the prestige of such an opportunity to bring in high-quality talent that might not have otherwise considered government service. The strong academic environment in Germany makes it more likely that programs like this can be successful in helping build internal capacity, and Germany should also consider how to best improve exchanges and networking between these sectors.128

- Consider the data needs of regulators—The oversight responsibilities of government ministries are also becoming more data-intensive, meaning that many public authorities will eventually need to be able to securely analyze private data for regulatory purposes.129 This will be especially true for ministries that are handed obligations through new EU legislation such as the AI Act.130 Although Germany has developed some relevant expertise through implementing the General Data Protection Regulation, most of the oversight from this act is enforced at the state level.131 In the near future, Germany will likely need to consider how its data infrastructure can support the expanding data analysis requirements of its regulating agencies.

- Survey government employees about data use—The analysis and discussion in this report are significantly limited by a lack of information about the everyday use of data by federal employees. It is not clear how capable the average federal employee is in interpreting, collecting, or analyzing data, nor is it clear if they have necessary data access for their jobs. Surveys of selected subsections of federal employees could shed further light on these questions, as well as how competencies vary across ministries. In the United States, the Data Foundation has developed surveys for senior data staff, including chief data officers132 and chief evaluation officers.133 Germany should implement internal government surveys and monitoring that get at these questions, both of senior staff such as the new chief data scientists, and of other federal employees who do not primarily work as data analysts.

- Delineate clear boundaries between technology authorities—A range of agencies and authorities have responsibilities relevant to governmental data use, including ITZBund, Digital Service 4 Germany, Destatis, the GovData.de platform team, as well as the upcoming ministry data labs, the Data Service Center, and the possible new data institute, among others. This ecosystem is sufficiently complex that these agencies are likely to build repetitive and overlapping expertise without a single document or strategy that clearly divides up organizational responsibilities. If an emergency data analysis is needed by the Chancellery, does the ministry data lab perform it, or can Digital Service 4 Germany? If a new data tool would help several ministries, does this task fall to the Data Service Center or ITZBund? A single governmental document with clear organizational responsibilities and boundaries could help answer these questions, and offer a comprehensive government-wide vision for data analytics responsibilities.

- Strengthen data science in civil society—Germany’s civil society policy research institutions, including think tanks, have only limited capacity in emerging data science methods, hampering innovation in civic data science. In the United States, independent think tanks lead the government on innovative uses of data science for policy research. For example, the Center for Security and Emerging Technology’s Map of Science, a categorization and analysis of 260 million scientific documents,134 enables conclusions about which countries are leading in AI-driven robotics research (i.e., that Germany leads the world in robotics for automotive engineering).135 Alternatively, the Urban Institute creates novel data systems for policymaking, such as the Spatial Equity Data Tool, which identifies geographic disparities across populations and the distribution of government services.136 These are just two examples of how civil society organizations can develop new data applications that government can use and build on. In Germany, while the Civic Innovation Platform has provided some funding for civil society innovation with data, 137 the €20,000 awards are not sufficient to support ongoing institutional efforts. Germany should increase this funding or create a new line of grants for expanding data science in independent policy research.

Alex C. Engler is a Stiftung Mercator Senior Fellow and Fulbright-Schuman Innovation Scholar, currently on a leave of absence from the Brookings Institution.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

[i] It is challenging to categorize governmental data use, which has both dependencies (e.g., analysis depends on data collection and storage) as well as cyclical elements (e.g., data analysis can affect what data is collected). Further, some data analyses may serve multiple purposes—a study intended to decide on an intervention’s efficacy might also be used to guide its future implementation (planning). Finally, information about how data is analyzed, as discussed here, does not necessarily inform how that analysis is used in day-to-day function of governance and policymaking, yet unfortunately, there is little systemic knowledge to draw conclusions on the latter.

[ii] This paper narrowly discusses the use of data analysis to inform civilian governance, which means that not every cell of government data is pertinent to this review. As one example, the data transmitted in video calls is not considered here, since government analysts themselves are not working directly with this data to inform their work. Instead of including every process in which some data is technically involved, this review focusses on the data that is analyzed for the key decisions of governance. Further, this paper discusses civilian use, and thus military applications are not considered here, nor are the German government’s efforts to improve data use in the private sector, which is a key goal of policies such as the National AI Strategy. Finally, cybersecurity issues are also left out, which is a significant omission due to the general importance of data security and to recent changes to Germany’s IT Cybersecurity law.

[iii] The German government digitalization is an enormous topic in itself. For a more thorough overview, see: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-53697-8_19

[iv] Compared to the United States, where there are 13 principal statistical agencies and 128 agencies with over $500,000 of statistical activities: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK447392/

[v] Using open source software for data analytics also aligns with Germany’s Strategy for Strengthening Digital Sovereignty for Public Administration IT.

-

Footnotes

- Behre, O. (1905). Geschichte der Statistik in Brandenburg-Prussen bis zur Gründung des Königlichen Statistichen Bureaus. http://www.ub.uni-koeln.de/utils/getfile/collection/digitalis/id/264/filename/272.pdf

- The global investment in digital governance is clearly observable across through indices from the United Nations, European Commission, and the OECD.

- Data Strategy of the German Federal Government. (2021). Federal Chancellery of the German Government. https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/998194/1950610/fb03f669401c3953fef8245c3cc2a5bf/datenstrategie-der-bundesregierung-englisch-download-bpa-data.pdf

- Bundesministerium der Finanzen (2020). Deutscher Aufbau- und Resilienzplan. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Europa/DARP/2-04-daten-als-rohstoff-der-zukunft.pdf

- Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community. “What is the Online Access Act?”https://www.onlinezugangsgesetz.de/Webs/OZG/EN/home/home-node.html

- Germany’s Presidency of the Council of the EU. (2020). Berlin Declaration on Digital Society and Value-Based Government. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/12/berlin-declaration-digitalization.html

- Koalitionsvertrag 2021 – 2025 zwischen der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN und den Freien Demokraten (2021). “Mehr Fortschritt Wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit.” https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf

- Redaktionsnetzwerk Deustchland. (December 8, 2021). “Neuer Minister Wissing baut sich eine Art Digitalministerium.” https://www.rnd.de/politik/volker-wissing-neuer-verkehrs-und-digitalminister-baut-sich-eine-art-digitalministerium-NZJ4RE6X7UWA24VY6FCW5RM4V4.html

- Beckedahl, Markus. (December 9, 2021) “Scholz wird kein Digitalkanzler.” Netzpolitik.

- OECD Directorate for Public Governance. (November 28, 2019) The Path to Becoming a Data-Driven Public Sector. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/gov/the-path-to-becoming-a-data-driven-public-sector-059814a7-en.html

- Münnich, Ralf., Schnell, Rainer., Brenzel, Hanna., Dieckmann, Hanna., Dräger, Sebastian., Emmenegger, Jana., Höcker, Philip., Kopp, Johannes., Merkle, Hariolf., Neufang, Kristina., Obersneider, Monika., Reinhold, Julian., Schaller, Jannik., Schmaus, Simon., & Stein, Petra. (2020) “A Population Based Regional Dynamic Microsimulation of Germany: The MikroSim Model.” University of Trier. https://mikrosim.uni-trier.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/M%C3%BCnnich-et-al.-2020.-A-Population-Based-Regional-Dynamic-Microsimulation-of-Germany-The-MikroSim-Model.pdf

- See, for example, those from the Ifo, ZEW, RWI, Kiel, and DIW institutes.

- Reister, Timo., Spengel, Christoph., Nicolay, Katharina., & Heckemeyer, Jost Henrich. (2008), ZEW Corporate Taxation Microsimulation Model (ZEW TaxCoMM), ZEW Discussion Paper No. 08-117, Mannheim. https://www.zew.de/publikationen/zew-corporate-taxation-microsimulation-model-zew-taxcomm

- Fraunhofer-Institut für Angewandte Informationstechnik. “Alterssicherung und Pflege.” https://www.fit.fraunhofer.de/de/geschaeftsfelder/mikrosimulation-und-oekonometrische-datenanalyse/alterssicherung.htm

- Gern, Klaus-Jürgen., Kooths, Stefan., Stolzenburg, Ulrich., & Reents, Jan. (December 15, 2022) World Economy Winter 2021: Transitory slowdown. Kiel Institute Economic Outlook World, Nr. 85, 2021 Q4. Ifw Kiel Institute for the World Economy. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kiel-institute-economic-outlook/2021/world-economy-winter-2021-transitory-slowdown-16843/

- Lehmann, Robert., Reif, Magnus., & Wollmershäuser, Timo. (2020). ifoCAST: The New Forecast Standard of the ifo Institute. Ifo Institute. https://www.ifo.de/en/publikationen/2020/article-journal/ifocast-new-forecast-standard-ifo-institute

- Gemeinschaftsdiagnose. “Die Gemeinschaftsdiagnose.” https://gemeinschaftsdiagnose.de/

- IMPREX. Flood early warning and forecasting across Europe: Germany. https://www.imprex.eu/system/files/generated/files/resource/flood-early-warning-and-forecasting-across-europe-germany_1.pdf

- Sardoschau, Sulin. (August 19, 2020). The Future of Migration to Germany: Assessing methods in migration forecasting. German Center for Integration and Migration Research. https://dezim-institut.de/fileadmin/Publikationen/Briefing_Notes/DBN_04_200910_The_Future_of_Migration_to_Germany-_Assessing_methods_in_migration_forecasting.pdf

- Fuchs, Johann., Söhnlein, Doris, & Vanella, Patrizio. (August 2, 2021). Migration Forecasting—Significance and Approaches. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 689–709. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8392/1/3/54/htm

- Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (August 2021). Entscheiderbrief Informationsschnelldienst. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Behoerde/Informationszentrum/Entscheiderbrief/2021/entscheiderbrief-07-2021.pdf

- Federal Foreign Office. (March 2021). Preventing Crises, Resolving Conflicts, Building Peace. https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2465762/a96174cdcf6ad041479110e25743bb20/210614-krisenleitlinien-download-data.pdf

- Rosche, Carsten. “United Nations E-Government Survey 2020 – Member States Questionnaire (MSQ)–Germany.” (March 29, 2019). https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/Portals/egovkb/MSQ/Germany_28012021_120902.pdf

- Hammerschmid, Gerhard. (November 6, 2020). “Implementing the Online Access Act (OAA) in Germany: A Unique Collaborative Effort to Advance Online Public Services in the German Federal System.” Tropico Project. https://tropico-project.eu/cases/administration-costs-for-bureaucracy/implementing-the-online-access-act-oaa-in-germany-a-unique-collaborative-effort-to-advance-online-public-services-in-the-german-federal-system/

- National Regulatory Control Council. (September 2021). Future-Proof State – Less Bureaucracy, Practical Legislation and Efficient Public Services. https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/resource/blob/656764/1960670/ae6c9535f5bec8f248cc72bb86a1214e/210916-annual-report-2021-data.pdf

- Informations Technik Zentrum Bund. (May 2021). ITZBund Geschäftsbericht 2020. 2020https://www.itzbund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/dasitzbund/Geschaeftsbericht_2020.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

- Informations Technik Zentrum Bund. “Die Bundescloud – eine exklusive, private Cloud für die Bundesverwaltung.” https://www.itzbund.de/DE/itloesungen/egovernment/bundescloud/bundescloud.html

- Informations Technik Zentrum Bund. “Bundescloud Entwicklungsplattform: State of the Art der Softwareentwicklung” https://www.itzbund.de/DE/itloesungen/standardloesungen/bundescloudentwicklungsplattform/bundescloudentwicklungsplattform_node.html;jsessionid=0BA536C05E8D009FD6AC8CB7831911A4.internet962

- Koalitionsvertrag 2021 – 2025 zwischen der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN und den Freien Demokraten (2021). “Mehr Fortschritt Wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit.” https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf

- Wölbert, Christian. (February 3, 2022). ‘SAP und Arvato versprechen “souveräne” Microsoft-Cloud für Behörden.’ Heise Online. https://www.heise.de/news/SAP-und-Arvato-versprechen-souveraene-Microsoft-Cloud-fuer-Behoerden-6346760.html

- Zeit Online. (February 3, 2022). “SAP und Arvato bauen Verwaltungs-Cloud mit Microsoft-Technik.” https://www.zeit.de/news/2022-02/03/sap-und-arvato-bauen-verwaltungs-cloud-mit-microsoft-technik

- Föderale IT-Kooperation. (November 2020). “Deutsche Verwaltungscloud-Strategie: Föderaler Ansatz.” https://www.cio.bund.de/SharedDocs/Publikationen/DE/Strategische-Themen/deutsche_verwaltungscloudstrategie.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

- Digital Service for Germany. “Für ein digitales Deutschland.” https://digitalservice4germany.org/

- The German Federal Government. (September 23, 2020). “Making digital administration more effective.” https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/federal-government/register-modernisation-act-1790662

- Official Journal of the European Union. (October 2, 2018). “Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a single digital gateway to provide access to information, to procedures and to assistance and problem-solving services and amending Regulation (EU) No 1024/2012.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.295.01.0001.01.ENG

- Bundesverwaltungsamt. “Überblick Registermodernisierung.” https://www.bva.bund.de/DE/Services/Behoerden/Verwaltungsdienstleistungen/Registermodernisierung/Ueberblick/ueberblick_node.html

- National Regulatory Control Council. (September 2021). Future-Proof State – Less Bureaucracy, Practical Legislation and Efficient Public. Services.https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/resource/blob/656764/1960670/ae6c9535f5bec8f248cc72bb86a1214e/210916-annual-report-2021-data.pdf

- Engelmann, Jan., & Puntschuh, Michael. (December 2020). KI IM BEHÖRDENEINSATZ: ERFAHRUNGEN UND EMPFEHLUNGEN. Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche IT & iRights.Lab.

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz. (July 29, 2021). “Automatisches Zustandsmonitoring von Autobahnen mit KI – ARC-D.” https://www.bmvi.de/SharedDocs/DE/Artikel/DG/mfund-projekte/ARC-D.html

- Engelmann, Jan., & Puntschuh, Michael. (December 2020). KI IM BEHÖRDENEINSATZ: ERFAHRUNGEN UND EMPFEHLUNGEN. Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche IT & iRights.Lab.

- Anlage 1: Anwendungsfälle von KI in Bundesministerien und nachgeordneten Behörden. https://mdb.anke.domscheit-berg.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/220125_KleineAnfrage_KI_Anlage1.pdf

- Anlage 3: Weitere Forschungsvorhaben, Pilotprojekte und Reallabore mit Beteiligung der Bundesministerien und nachgeordneter Behörden. https://mdb.anke.domscheit-berg.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/220125_KleineAnfrage_KI_Anlage3.pdf

- Domscheit-Berg, Anke. (January 25, 2022). “MEINE ANFRAGE ZEIGT: BUNDESREGIERUNG IGNORIERT RISIKEN IM BEREICH KÜNSTLICHE INTELLIGENZ.” https://mdb.anke.domscheit-berg.de/2022/01/kleine-anfrage-ki-risiken-bundesregierung/

- Anlage 2: Angaben zur externen Entwicklung von Systemen. https://mdb.anke.domscheit-berg.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/220125_KleineAnfrage_KI_Anlage2.pdf

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). (2020). Das system der amtlichen Statistik: Organisation und Zusammenarbeit im nationalen, europäischen und internationalen Kontext. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Ueber-uns/Unsere-Aufgaben/system-der-amtlichen-statistik.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

- Institute for Employment Research. “Research Data Centre – Overview of Available Data.” https://fdz.iab.de/en/FDZ_Overview_of_Data.aspx

- Robert Koch Institute. “Health Reporting.” https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Health_Monitoring/Health_Reporting/fed_health_reporting_node.html

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). (March 2019). Digital Agenda des Statistischen Bundesamtes. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Service/OpenData/Publikationen/digitale-agenda.pdf;jsessionid=00B0554A8B7DD01A593C6D01C4BB9A3F.live712?__blob=publicationFile

- Keusch, Florian. “IAB-SMART: Evaluating digital trace data to examine social integration, social networks, and work-related stress in the labor market context.” https://floriankeusch.weebly.com/iab-smart.html

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). “EXDATA – Experimental Data.” https://www.destatis.de/EN/Service/EXDAT/_node.html;jsessionid=D0DDF42CBC587C05A450082143BB986C.live721

- Corona data donation. “About the project.” Rober Koch Institute. https://corona-datenspende.de/science/en/

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). (June 2016). Strategy And programme plan. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00022290/StrategieProgrammplan2016_2020en.pdf;jsessionid=FDB8D20D0192A1906072DF9FFA0CD27C

- Engler, Alex. (April 20, 2020). “What all policy analysts need to know about data science.” Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-all-policy-analysts-need-to-know-about-data-science/

- Sharma, Manon Rani., Freudi, Daniel., Münch, Claudia., Schindler, Eva., & Wegrich, Kai. (December 6, 2013). Expert report on the implementation of ex-post evaluation. Prognos. https://www.normenkontrollrat.bund.de/resource/blob/656764/775370/00837e2d07a0f6230b155a656a412694/2014-evaluation-report-data.pdf?download=1

- Stockman, Reinhard., Meyer, Wolfgang., & Taube, Lena. (2020). The Institutionalisation of Evaluation in Europe. Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-32284-7

- Ibid.

- German Institute for Development Evaluation. “Goals and function”. https://www.deval.org/en/about-us/the-institute/goals-and-functions

- Jacobi, Lena., & Kluve Jochen. (October 2006). Before and After the Hartz Reforms: The Performance of Active Labour Market Policy in Germany*. Journal for Labour Market Research / Zeitschrift für Arbeitsmarktforschung, 2007, 40 (1), 45-64. https://doku.iab.de/zaf/2007/2007_1_zaf_jacobi_kluve.pdf

-

Institute for Employment Research. “Evaluation der Arbeitsmarktinstrumente”

https://www.iab.de/en/forschung-und-beratung/forschungsschwerpunkte/forschungsprojekte-nach-themen.aspx/Themenprojekte/203 - Stockman, Reinhard., Meyer, Wolfgang., & Taube, Lena. (2020). The Institutionalisation of Evaluation in Europe. Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-32284-7

-

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz. “Evaluationen.”

https://www.bmwi.de/Navigation/DE/Service/Evaluationen/evaluationen.html - Leibniz Association. “Leibniz Institutes – All lists.” https://www.leibniz-gemeinschaft.de/en/institutes/leibniz-institutes-all-lists

- Zimmermann, Klaus. (2011). Evidenzbasierte Politikberatung. Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung, Vol. 80 (2011), Iss. 1: pp. 23–33. https://elibrary.duncker-humblot.com/journals/id/25/vol/80/iss/1451/art/4730/

- Bender, Stefan., Burghardt, Anja., & Schiller, David. (January 2014). International Access to Administrative Data for Germany and Europe. German Data Forum (RatSWD). The RatSWD Working Paper Series. https://www.konsortswd.de/wp-content/uploads/RatSWD_WP_229.pdf

- German Data Forum (RatSWD). ‘Data Access for Science and Research – the “Research Data Centre” success story’ https://www.ratswd.de/en/forschungsdaten/fdz/wirtschaft/

- United States Census Bureau. “Research Data Centers.” https://www.census.gov/about/adrm/fsrdc/locations.html

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz. (October 2, 2021). “Zweites Open-Data-Gesetz und Datennutzungsgesetz.” https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Artikel/Service/Gesetzesvorhaben/zweites-open-data-gesetz-und-datennutzungsgesetz.html

- Deutscher Bundestag. (October 10, 2019). Erster Bericht der Bundesregierung über die Fortschritte bei der Bereitstellung von Daten. 19/14140. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/19/141/1914140.pdf

- GovData.de. “Das Datenportal für Deutschland Open Government: Verwaltungsdaten transparent, offen und frei nutzbar.” https://www.govdata.de/

- Oswald, Bernd. (July 7, 2021). “Open-Data-Strategie: Mehr offene Daten, aber kein Rechtsanspruch.” GovData.de. https://www.br.de/nachrichten/netzwelt/open-data-strategie-mehr-offene-daten-aber-kein-rechtsanspruch,ScgENet

- Wittmann, Lilith. (December 1, 2021). “bund.dev: Updates Dezember 2021.” bundDEV Verwaltung Digital. “Unsere Schnittstellen.” https://lilithwittmann.medium.com/bund-dev-updates-dezember-2021-b903dbeb33c4

- Koalitionsvertrag 2021 – 2025 zwischen der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN und den Freien Demokraten (2021). “Mehr Fortschritt Wagen: Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit.” https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf

- Jacob, Steve., Speer, Sandra., & Furubo, Jan-Eric. (January 2015). “The institutionalization of evaluation matters: Updating the International Atlas of Evaluation 10 years later.” Evaluation 21(1):6-31. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273339192_The_institutionalization_of_evaluation_matters_Updating_the_International_Atlas_of_Evaluation_10_years_later

- Stockman, Reinhard., Meyer, Wolfgang., & Taube, Lena. (2020). The Institutionalisation of Evaluation in Europe. Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-32284-7

- Verein für Socialpolitik. (September 6, 2015). “LEITLINIEN UND EMPFEHLUNGEN DES VFS FÜR EX POST-WIRKUNGSANALYSEN.” https://www.socialpolitik.de/de/leitlinien-und-empfehlungen-des-vfs-fuer-ex-post-wirkungsanalysen

- Halle Institute for Economic Research. “CENTRE FOR EVIDENCE-BASED POLICY ADVICE (IWH-CEP).” https://www.iwh-halle.de/en/about-the-iwh/iwh-cep/centre-for-evidence-based-policy-advice/

- Digitalakademie Bund in der Bundesakademie für öffentlichen Verwaltung im Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat. “Willkommen in der Digitalakademie.” https://www.digitalakademie.bund.de/DE/Digitalakademie/Willkommen/willkommen_node.html

- Bundesakademie für öffentliche Verwaltung im Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat. “Interaktives FortbildungsSystem für die Bundesverwaltung.” https://www.ifosbund.de/pub/index.xhtml

- Stiftung Neue Verantwortung. “Data science unit.” https://www.stiftung-nv.de/en/project/data-science-unit

- Bertelsman Stiftung. (March 4, 2020). “Projects for a strong Europe, more innovative capacity and new approaches to digitalization” https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/topics/latest-news/2020/march/projects-for-a-strong-europe-more-innovative-capacity-and-new-approaches-to-digitalization

- Civic Innovation Platform. “Gemeinsam wird es KI!” https://www.civic-innovation.de/start

- Hertie School. “Master of Data Science for Public Policy.” https://www.hertie-school.org/en/mds

- University of Konstanz. “MSc Social and Economic Data Science.” https://www.wiwi.uni-konstanz.de/en/study/master-of-science/seds/

- Mannheim Business School. “Mannheim Master of Applied Data Science & Measurement” https://www.mannheim-business-school.com/en/mba-master-and-courses/masters-programs/mannheim-master-of-applied-data-science-measurement/

- Digital Skills and Jobs Platform. “Master in Artificial Intelligence for Public Services (AI4Gov)” The European Union. https://digital-skills-jobs.europa.eu/en/opportunities/training/master-artificial-intelligence-public-services-ai4gov

- Stanford Center for Human-Centered AI. Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2021. Stanford University. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-AI-Index-Report_Master.pdf

- Stanford Center for Human-Centered AI. “Global AI Vibrancy Tool.” Stanford University. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/vibrancy/

- Freist, Roland. (January 11, 2020). “100 new AI professorships in Bavaria.” Hannover Messe. https://www.hannovermesse.de/en/news/news-articles/100-new-ai-professorships-in-bavaria

- Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung. (November 24, 2021). “New Alexander von Humboldt Professors selected.” https://www.humboldt-foundation.de/en/explore/newsroom/press-releases/new-alexander-von-humboldt-professors-selected

- Boytchev, Hristio. (March 27, 2019). “An introduction to the complexities of the German research scene.” Nature 567, S34-S35. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00910-7

- Stanford Center for Human-Centered AI. Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2021. Stanford University. https://aiindex.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-AI-Index-Report_Master.pdf

- European Investment Bank. (2020). “Who is prepared for the new digital age? : evidence from the EIB investment survey”, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2867/974122

- The European Commission. (2021). Germany DESI Country Profile. The Digital Economy and Society Index. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/countries-digitisation-performance

-

Hölscher, Ines., Opiela, Nicole., Tiemann, Jens., Gumz, Jan Dennis., Goldacker, Gabriele., Thapa, Basanta., & Weber, Mike. (May 2021). Deutschland-Index Der Digitalisierung 2021. Kompetenzzentrum Öffentliche IT.

https://www.oeffentliche-it.de/documents/10181/14412/Deutschland-Index+der+Digitalisierung+2021 - Mergel, Ines. (January 30, 2021). Digital Transformation of the German State. Public Administration in Germany pp 331-355. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-53697-8_19

- Holligan, Anna. (January 15, 2021). “Dutch Rutte government resigns over child welfare fraud scandal.” BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55674146

- Elyounes, Doaa Abu. (February 10, 2021). “Why the resignation of the Dutch government is a good reminder of how important it is to monitor and regulate algorithms” Berkman Klein Center Collection. https://medium.com/berkman-klein-center/why-the-resignation-of-the-dutch-government-is-a-good-reminder-of-how-important-it-is-to-monitor-2c599c1e0100

- Morey, Timothy., Fornath, Theodore., & Schoop, Allison. (May 2015). “Customer Data: Designing for Transparency and Trust.” Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/05/customer-data-designing-for-transparency-and-trust

- Initiative 21. (November 2018). eGovernment Monitor 2018: Nutzung und Akzeptanz digitaler Verwaltungsangebote – Deutschland, Österreich und Schweiz im Vergleich. https://initiatived21.de/app/uploads/2018/11/191029_egovmon2018_final_web.pdf

- The European Commission Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. (2021). Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2021. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/desi

- The European Commission Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology. “DESI by Components” https://digital-agenda-data.eu/charts/desi-components

- Ubaldi, Barbara., & Tomoya. Okubo (2020), “OECD Digital Government Index (DGI): Methodology and 2019 results”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 41, OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/b00142a4-en.pdf?expires=1644602283&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=1ABC3517198CAAEBA5A37906F6557290

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2020). UN E-Government Survey 2020. https://publicadministration.un.org/egovkb/en-us/Reports/UN-E-Government-Survey-2020

- Bundesministerium der Finanzen (2020). Deutscher Aufbau- und Resilienzplan. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Europa/DARP/2-04-daten-als-rohstoff-der-zukunft.pdf

- U.S. Department of Commerce. “Commerce Data Academy.” https://www.commerce.gov/page/commerce-data-academy

- Jeff Chen, former Chief Data Scientist of the US Department of Commerce, personal communication. (December 17, 2021).

- Digitalakademie Bund in der Bundesakademie für öffentlichen Verwaltung im Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat. “Von ihrer Geburt bis zum Tod: Was Daten so alles erleben.” https://www.digitalakademie.bund.de/SharedDocs/03_Episoden/Lernreise_01/03_Was_Daten_so_alles_erleben.html?cms_ref=081445b3-a2da-4a4b-a768-a592a75a5b85

- Wiseman, Jane. (September 3, 2019). The Case for Government Investment in Analytics: Why Every Government Executive Should Care About Data. Data Smart City Solutions, Harvard University.

- Sloane, Mona., Chowdhury, Rumman., Havens, John C., Lazovich, Tomo., Rincon Alba, Luis C. (2021). AI and Procurement: A Primer. New York University. https://archive.nyu.edu/bitstream/2451/62255/2/AI%20and%20Procurement%20Primer%20Summer%202021.pdf

- Mashariki, Amen Ra. (May 27, 2020). We Have Fire Drills, Why Governments Need to Run “Data Drills” as Well. Beeck Center, Georgetown University. https://beeckcenter.georgetown.edu/we-have-fire-drills-why-governments-need-to-run-data-drills-as-well/

- Green, Ben. (2019). The Smart Enough City: Putting Technology in Its Place to Reclaim Our Urban Future. The MIT Press. https://books.google.de/books?id=NlT5DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA124&lpg=PA124&dq=nyc+moda+data+drills&source=bl&ots=sP19ZMJtQ7&sig=ACfU3U06qjiaSWzMbkRolEFuesjtJfF_yw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjeioSXnPf0AhUpSfEDHclQAHMQ6AF6BAgiEAM#v=onepage&q=nyc%20moda%20data%20drills&f=false

- Der Tagesspiegel. (July 14, 2019). “Behörden wollen IT-Fachkräfte mit deutlich mehr Geld locken.” https://www.tagesspiegel.de/wirtschaft/80-000-euro-praemie-behoerden-wollen-it-fachkraefte-mit-deutlich-mehr-geld-locken/24588500.html

- Gerhardt, Lauren., & Headd, Mark. (April 9, 2019). “Why we love modular contracting.” https://18f.gsa.gov/2019/0/09/why-we-love-modular-contracting/

- Nyczepir, Dave. (January 15, 2021). “USDS pilot to hire data scientists at 10 agencies closed in less than 2 days” Fedscoop. https://www.fedscoop.com/10-agencies-data-scientists/

- Pahlka, Jennifer. (February 4, 2021). “What on earth is SME-QA and why should you care about it?” Jennifer Pahlka Medium. https://pahlkadot.medium.com/what-on-earth-is-sme-qa-and-why-should-you-care-about-it-66383167387c

- Jones, John Hewitt. (November 3, 2021). “White House appoints Denice Ross as US chief data scientist.” Fedscoop. https://www.fedscoop.com/white-house-appoints-denice-ross-as-us-chief-data-scientist/

- UK Central Digital and Data Office. (November 29, 2021). “UK government publishes pioneering standard for algorithmic transparency.” https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-government-publishes-pioneering-standard-for-algorithmic-transparency

- Johnson, Khari. (September 28, 2020). “Amsterdam and Helsinki launch algorithm registries to bring transparency to public deployments of AI.” Venture Beat. https://venturebeat.com/2020/09/28/amsterdam-and-helsinki-launch-algorithm-registries-to-bring-transparency-to-public-deployments-of-ai/

- White House Office of Management and Budget. (2021). Federal Data Strategy Action Plan. https://strategy.data.gov/assets/docs/2021-Federal-Data-Strategy-Action-Plan.pdf

- Engstrom, David Freeman., & Ho, Daniel E. (August 2020). “Algorithmic Accountability in the Administrative State.” Yale Journal on Regulation. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/8311/03_Engstrom__Ho_Article._Final.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Government of Canada. (April 4, 2021). “Algorithmic Impact Assessment Tool.” https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/digital-government-innovations/responsible-use-ai/algorithmic-impact-assessment.html

- Ada Lovelace Institute. (March 10, 2021). “Algorithmic impact assessment in healthcare.” https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/project/algorithmic-impact-assessment-healthcare/

- Schupmann, Will., & Fudge, Keith. (June 2019). Chief Evaluation Officers. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98767/chief_evaluation_officers_1.pdf

- Mumford, Steve., & Hart, Nick. (2021). Federal Evaluation Officials: 2021 Survey Results on Agencies’ Emerging Evaluation Capacity to Implement the Evidence Act. The Data Foundation. https://www.datafoundation.org/survey-of-federal-evaluation-officials-2021

- The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2021). Government at a Glance 2021 Country Fact Sheet. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/gov/gov-at-a-glance-2021-germany.pdf

- Digital Services 4 Germany. “Tech4Germany ist das Fellowship-Programm des Bundes für nutzerzentrierte Software-Entwicklung.” https://digitalservice.bund.de/tech4germany/

- OECD Observatory of Public Sector Information. “Civic Digital Fellowship.” OPSI Case Study. https://www.oecd-opsi.org/innovations/civic-digital-fellowship/

- Kupi, Maximilian., Jankin, Slava., & Hammerschmid, Gerhard. (January 24, 2022). Data Science and AI in Government. The Hertie School. https://hertieschool-f4e6.kxcdn.com/fileadmin/2_Research/2_Research_directory/Research_Centres/Centre_for_Digital_Governance/2020-01_Documents/HS_Policy_Brief_English_Final_Version_Print.pdf

- Engler, Alex. (September 9, 2020). “The Devil is in the Data.” Lawfare. https://www.lawfareblog.com/devil-data

- MacCarthy, Mark., & Propp, Kenneth. “Machines Learn That Brussels Writes the Rules: The EU’s New AI Regulation” Lawfare. https://www.lawfareblog.com/machines-learn-brussels-writes-rules-eus-new-ai-regulation

- Landesbeauftragte für Datenschutz und Informationsfreiheit Nordrhein-Westfallen. “Data protection authorities in Germany.” https://www.ldi.nrw.de/LDI_EnglishCorner/mainmenu_DataProtection/Inhalt2/authorities/authorities.php