This article originally appeared in the Las Vegas Sun.

Inequality, the issue that set Bernie Sanders’ run for the Democratic nomination alight, has gone underground in the presidential contest.

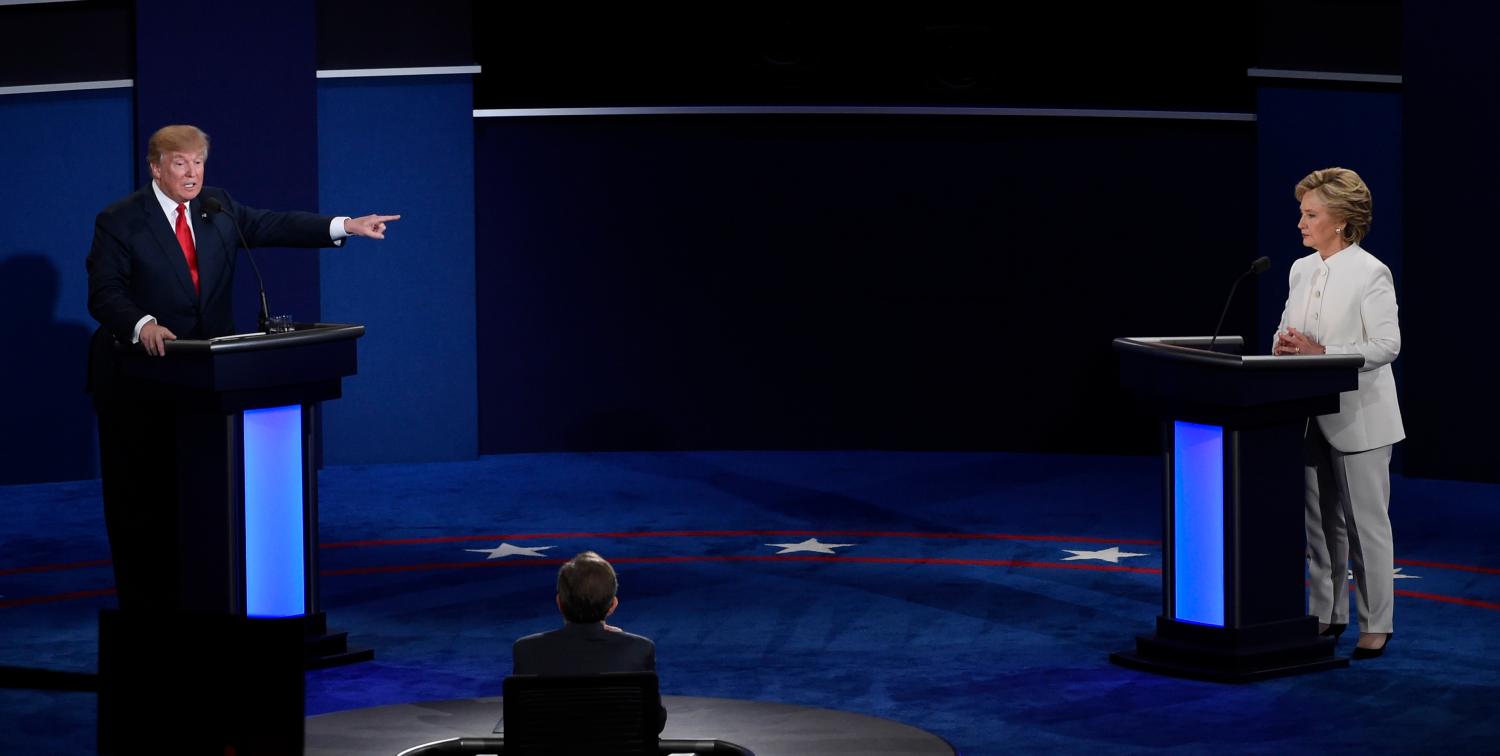

Hillary Clinton has occasionally tried to make political capital out of Donald Trump’s financial capital, most recently accusing him of proposing a child care tax-break that would “benefit wealthy families just like his own.”

But this is difficult territory for Clinton. She blundered by describing Bill and herself as “dead broke” when they left the White House. When she was struggling to fend off Sanders, leading figures in her own party were critical of her stance on inequality. Joe Biden heaped praise on Sanders for his “authenticity” on the issue before acidly noting that Clinton was “relatively new” to it. Add in her stratospheric speaker fees, the couple’s estimated net worth of more than $100 million and the recent furor over the funding of the Clinton Foundation, and it’s easy to see why inequality might feel like a double-edged sword to her campaign.

While Clinton tries to downplay her wealth, Trump glories in his own, conveniently forgetting that it was inherited. He uses his giant airplane as a prop at rallies and boasts about the size of his balance sheet. Refusing to release tax returns would be a fatal mistake for a traditional candidate in a normal election. It has barely dented Trump.

The race looks, on the surface, like a culture contest: white vs. minority; educated vs. uneducated; blue-collar vs. professional elite; nostalgia vs. optimism; nativism vs. cosmopolitanism. But while inequality has become a politically subterranean issue, it is nonetheless shaping the politics of 2016. Trump’s supporters are not especially poor or suffering from free-trade policies, according to a comprehensive study by Gallup. But they are more likely to live in areas with low rates of upward mobility and shorter-than-average life expectancy. In TrumpLand, compared with the rest of America, prospects are limited and life is short.

Clinton’s policies on issues such as taxes, child care, college funding and paid leave would inject a modest dose of redistribution. But she is understandably too fearful of the upper-middle class, and of accusations of hypocrisy, to push this agenda hard. Trump does not have a policy platform (after all, a platform is a stable structure of some kind), but he occasionally throws out ideas with potentially progressive implications, such as large public investments in infrastructure and the abolition of certain tax breaks. But taken as a whole, his plans would hugely increase economic inequality, according to a careful analysis by the Brookings-Urban Tax Policy Center.

Trump is not interested in reducing inequality. But it seems as if much of his support is coming from people who feel like they are falling behind and are looking for someone to blame: immigrants, “crooked” politicians, welfare recipients. They know Trump is extreme and a volatile anti-politician. It is not his ideas that attract them, it is his identity.

These are people who feel that the technocratic, rationalist elite has created a world that is amazing for themselves but much less awesome for everyone else. The hard part is that, however much we may dislike its expression, there is more than a kernel of truth here.

Political change is not an orderly process, and people do not always conform readily to the models of political scientists. In times like these, history is more useful than political science. As Richard Hofstadter reminded us in his book, “The Age of Reform,” the populist movement, often romanticized by those on the political left, was strongly flavored by nativism and even racism. “The demand for reform, many of them aimed at genuine ills,” he wrote, “was combined with strong moral convictions and hatred as a kind of creed.”

Describing the history of these movements in 19th- and 20th-century America, Hofstadter referred to the challenge of finding the line between “useful and valid criticism of a society and destructive alienation from its essential values.”

Precisely the same test faces us now. The temptation to dismiss Trump’s supporters as narrow-minded bigots is great, especially when some of them fit the description perfectly. Hatred does indeed seem to be their creed. But this won’t do.

It seems unlikely that Trump will win in November, though given recent polls, I wouldn’t bet the farm on it. And even if he loses, there is a good chance he will win the majority of white votes. There is a sense among some potential voters that the American dream is slipping out of their reach. Whites in particular are becoming the pessimists of our society; recent evidence suggests that drug addiction and suicide rates are rising among middle-aged white Americans.

As a general rule, Americans are not as troubled by the gap between the rich and the rest as the citizens of other nations, so long as they feel that wealth is earned fairly. The health of the American dream is not captured by narrow measures of income inequality. Rather, it is about equality in both the sense and the substance of real opportunity, of individual possibility.

As MSNBC political analyst Chris Hayes has written, “Americans rise from their class, not with it.” I think that’s right, and unlike Hayes, I think that this is mostly a good thing. The problem is that class mobility is now lower in the U.S. than in most other countries, and especially so in the places leaning toward Trump.

Many Americans feel, for want of a better word, stuck. And they are getting sick of that feeling. Trump has brilliantly found a way to tap that vein. His political rise reflects their perceived fall. Whatever we think of him, we also need to think hard about how to restore the elements of American equality that are being lost.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Inequality built the Trump coalition, even if he won’t solve it

September 26, 2016