As part of the Research on Scaling the Impact of Innovations in Education (ROSIE) project, we’ve been investigating how government decisionmakers choose education innovations for their countries—and the combination of forces shaping their decisionmaking. Our recent report examined these decision-making processes in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly around educational technology (edtech).

For the research informing this report, we conducted hour-long interviews with 10 central-government decisionmakers in LMICs and 10 edtech academics, tech industry experts, and representatives from the global education funding community. We also reviewed existing literature and drew on knowledge from our three years of ROSIE research.

We found that when it comes to edtech, most LMIC decisionmakers are already primed to adopt it. They don’t particularly care about evidence on edtech’s feasibility, sustainability, or impact because their motivation for edtech primarily derives from other sources. Additionally, their views regarding which edtech to prioritize appear to be misaligned with what research and many edtech experts view to be the value of edtech innovations in LMICs.

We believe this can change.

What influences policymakers’ edtech decisions?

When it comes to making decisions around edtech innovations, we identified four factors that exert significant pressure for decisionmakers to adopt edtech:

- In-country pressure for going digital. Country presidents, parents, and other departments within the government often call for edtech because it’s perceived as necessary for a nation to be considered a modern country.

- Donor priorities. Some donor organizations’ prioritization of edtech creates a financial incentive for policymakers to adopt it (especially given that LMICs have limited education budgets). It also signals to decisionmakers that edtech must be a valuable investment for education: If the funders like it, it must be good.

- Signaling. The prevalence of edtech in wealthy education systems signals to LMIC decisionmakers that “successful” education systems are filled with edtech, and few national leaders want to be perceived as uncommitted to building a high-quality, 21st century education system.1

- Tech company marketing. Government decisionmakers are bombarded by marketing from edtech companies hoping to increase market share. Many of these pitches are sophisticated and include information that looks like solid evidence for the innovation, and many decisionmakers lack the training and time to properly evaluate the companies’ claims.

What kind of edtech do decisionmakers consider?

Our interviews revealed that many decisionmakers seem primarily focused only on three categories of (the rather diverse array of) edtech innovations: “shiny edtech,” education management information systems (EMIS), and artificial intelligence. “Shiny edtech” is our term for innovations that look exciting and cutting-edge, regardless of their demonstrated impact. This includes edtech and practices like distributing digital devices to students, adaptive learning software for the classroom, and digital content displays. EMIS innovations, while less “exciting,” have a proven ability to help administrators run school systems more effectively and accurately and can offload some of teachers’ non-teaching tasks—allowing them more instructional time with students. And artificial intelligence-based innovations, as the new kid on the edtech block, currently dominate many government education decisionmaking conversations. When “shiny edtech” receives most of the attention, the myriad other applications of edtech—including proven EMIS—get deprioritized.

The edtech experts from our study expressed caution against “shiny edtech,” noting that these innovations tend to be difficult to scale, expensive to sustain, and have little (or no) firmly demonstrated positive effects on student learning outcomes. They, however, make for good retail politics and are what many tech companies are pitching. EMIS received broad support both from the experts we interviewed and our reviews of the research, while AI-based innovations are too new and disruptive for us to evaluate right now.

How useful is the current research on edtech?

We found that evidence plays a minor role in decisionmakers’ thinking around edtech innovations. Instead, the key factors are (1) who is recommending the edtech innovation, (2) how its deployment will look politically for the government, and (3) the reputation of the innovation or company.

In the rare cases where decisionmakers do want evidence, it’s hard to find, rarely relevant to their situation, and difficult to use. Available research is often outdated (it takes a few years to complete and by then the field has moved on), hard to understand (academic pieces written in technical prose rife with statistical tables), difficult to apply to one’s own specific context, and—in the case of research commissioned by tech companies themselves—not independently reviewed. Some organizations are filling this gap by producing accessible and high-quality research;2 however, the exponential growth of edtech innovations means that finding specific evidence for a single innovation under consideration can be like locating a needle in a haystack.

A framework for making good decisions

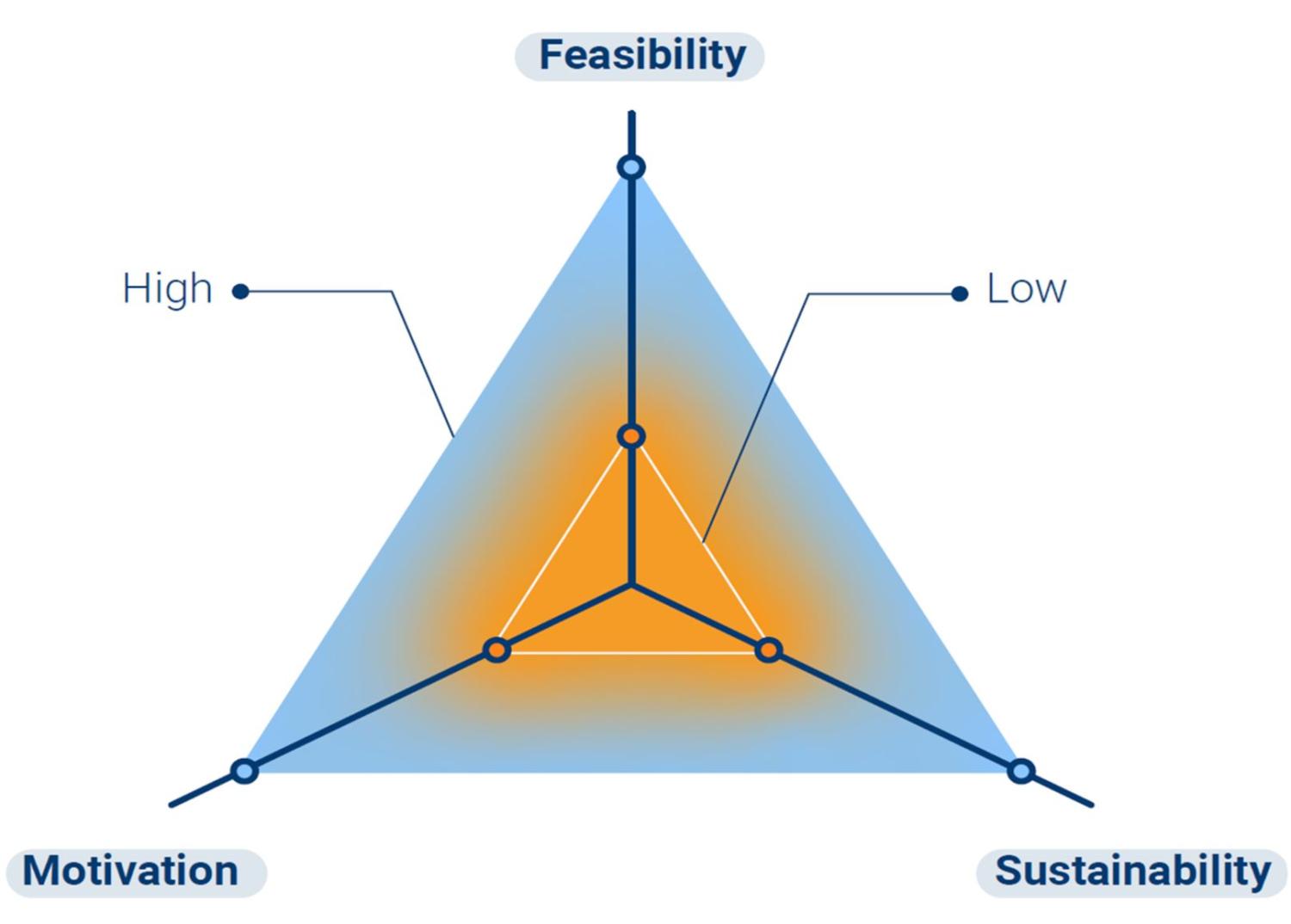

Analyzing our data, we saw that most government decisionmakers—intentionally or not—tended to evaluate edtech innovations along three different continua: their motivation to adopt the innovation, the feasibility of implementing the innovation, and the innovation’s potential sustainability for more than a few years. We believe that making this tri-level cognitive calculus visible supports strategic reflection for decisionmakers to more systematically, and with the right evidence, consider and evaluate any proposed innovation for implementation at scale in their jurisdiction. Imagine a three-dimensional plane:

Figure 1. Framework for education decisionmaking

Each of the three continua is an axis that goes from low to high. The higher up the axis, the more favorable an innovation is. For example, we saw some decisionmakers frame changes in education funding reforms and infrastructure as highly motivated in their jurisdiction and very sustainable but not feasible. Edtech-learning innovations (like digital literacy learning apps) were sometimes framed as motivated, feasible attempts at long-term impact but with resignation that such optimism was overstated because these kinds of reforms cycle through and are therefore not sustainable.

Use of this heuristic (which isn’t limited to edtech innovations—it can be used for any education innovation under consideration) enables decisionmakers and technical advisors to have candid conversations about the potential of individual innovations in their location. It clarifies a sometimes murky decisionmaking process. It also illuminates where additional evidence is needed. The sequence here is to (1) evaluate where a given innovation sits on all three axes, (2) discuss its potential on each continuum, and, if it still seems appropriate to consider the innovation, (3) figure out what additional information would be needed to push the innovation higher up each continuum. If the innovation under consideration does not ultimately sit high on all three continua, it’s probably not the right choice.

We hope use of this framework can support decisionmakers in being clearer about their reasonings and identifying what data they need to make smart decisions around education innovations. We also encourage funders, edtech providers, and scaling implementers to use this heuristic to think about how to move their own preferred edtech innovations further along each continuum. In this way, it’s our motivation that data-informed decisionmaking becomes feasible so that promising innovations are sustainably implemented.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This project is part of and supported by the Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (KIX), a joint partnership between the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of GPE, IDRC, or their Boards of Directors.

-

Footnotes

- And yet, pre-COVID19 in the U.S., 67% of purchased edtech products and software were not being used and an average of 97% were not being used intensively.

- For example, Central Square Foundation, Education Alliance Finland, and EdTech Hub.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How to improve government decisionmaking around edtech innovations

November 20, 2023