This paper was written for an October 14 Center on the United States and Europe virtual workshop on “Europe, China, and the United States” as part of Brookings’s Reimagining Europe’s security project, along with Abigaël Vasselier and Tara Varma’s “How should Europe position itself for systemic rivalry with China?”

Dreams of a fully united American and European front toward China are over. Although Washington, Brussels, and other European capitals have much in common when it comes to dealing with Beijing, they are now more likely to cooperate out of necessity than goodwill. Going forward, transatlantic leaders will have to manage competing interests by aligning approaches where possible while avoiding policy decoupling where necessary. This essay examines how best to do so by assessing the constraints inhibiting cooperation on China strategy and then identifying specific opportunities for policy convergence in the economic and security domains.

Constraints on cooperation

The United States has traditionally treated Europe as a source of power that could be drawn upon to help address global challenges. Although leaders in Washington, Brussels, and other European capitals often did not see eye-to-eye, they still found ways to coordinate responses on China across a wide range of issues. But as the unipolar moment fades and leaders in Washington contemplate retrenchment from overseas commitments, the Trump administration has come to see Europe as a power drain rather than a force multiplier. Some American officials have even urged European counterparts to focus on the continent, rather than getting distracted by activities in the Indo-Pacific.

This new way of thinking comes just as Europe’s willingness to follow America’s lead on China is waning. In some capitals, Washington is now seen as even more unpredictable and coercive than Beijing—a rogue superpower. In other capitals, leaders are understandably preoccupied by their own security concerns related to Russia. The reality is that the United States and Europe do have some divergent interests regarding China. Security concerns related to China’s actions in Asia are more important in Washington than in Brussels, for understandable reasons. This difference will make transatlantic security cooperation on Chinese actions in Asia all the more difficult.

Therefore, observers should openly acknowledge four constraints that will limit transatlantic cooperation on China going forward. First, as the world becomes more fragmented and multipolar, the United States and European countries are likely to find that cooperation will be more issue-specific. Although there is still potential for Washington and Brussels to work together, China will have many opportunities to drive wedges between the two when transatlantic interests diverge. The possibility of a major break in the transatlantic alliance is lower now than it was at the beginning of 2025, but the Trump administration’s unpredictability will push many in Europe to hedge against a downturn in relations with Washington. In some capitals, this will make cooperation with China attractive on certain issue sets, despite American leaders’ protestations. As a result, Beijing will find that wedge issues can sometimes push the United States and Europe apart, unless the two carefully coordinate their approaches.

Second, neither the United States nor Europe has an internally unified approach to China. Leaders on both sides of the Atlantic have expressed heightened concern about Chinese behavior in recent years, but they have yet to develop a strategy with broad-based political support. Any China consensus that previously existed in Washington has been severely tested in the second Trump administration’s first year. President Donald Trump’s worldview appears to reflect a spheres-of-influence logic, in which the United States should give China greater latitude in East Asia. Others in his administration appear to favor retrenchment, withdrawing U.S. forces from abroad to focus more on homeland defense. Meanwhile, some officials advocate prioritization of China over lesser competitors. The Trump administration is unlikely to articulate a single strategy, but rather embrace elements of spheres of influence, retrenchment, and prioritization strategies at different times and on different issues. Similarly, European approaches toward China vary dramatically depending on the capital one visits and who holds power. As a result, cooperation is likely to be episodic, depending significantly on the leaders directing key polices at any given moment.

Third, as the United States and Europe increasingly focus on their own individual interests, they are likely to prioritize different issues vis-à-vis China. Security considerations in Asia are foremost for some in the Trump administration, particularly related to Taiwan. Conversely, China’s support for Russia is the top China-related security issue for many in Europe. Meanwhile, economic issues may be most European policymakers’ prime concern, given the impact that China’s industrial policy is having on a range of critical European industries. Against this backdrop, Washington’s coercive economic policies and its insistence that Europe increasingly fend for itself against Russia will impede a great deal of cooperation. This implies that transatlantic cooperation on China will require trades across different issue areas.

Fourth, even in the economic arena, cooperation will be challenging due to transatlantic tensions over trade, tax, and technology policies. The United States and Europe have more in common economically than they do with China. But the current perception that both Washington and Brussels are taking advantage of each other will hamper cooperation. Therefore, the United States and Europe will be suspicious of one another’s intentions regarding China, and efforts will need to be made to minimize these disagreements over time.

Taken together, these constraints suggest that cooperation between the United States and Europe will likely be issue-based, episodic, economically focused, and often guarded. This is not a recipe for a straightforward partnership. Instead, leaders in Washington and key European capitals will have to develop policies and methods of cooperation that are robust against the inevitable political shifts that will continue to characterize the transatlantic relationship.

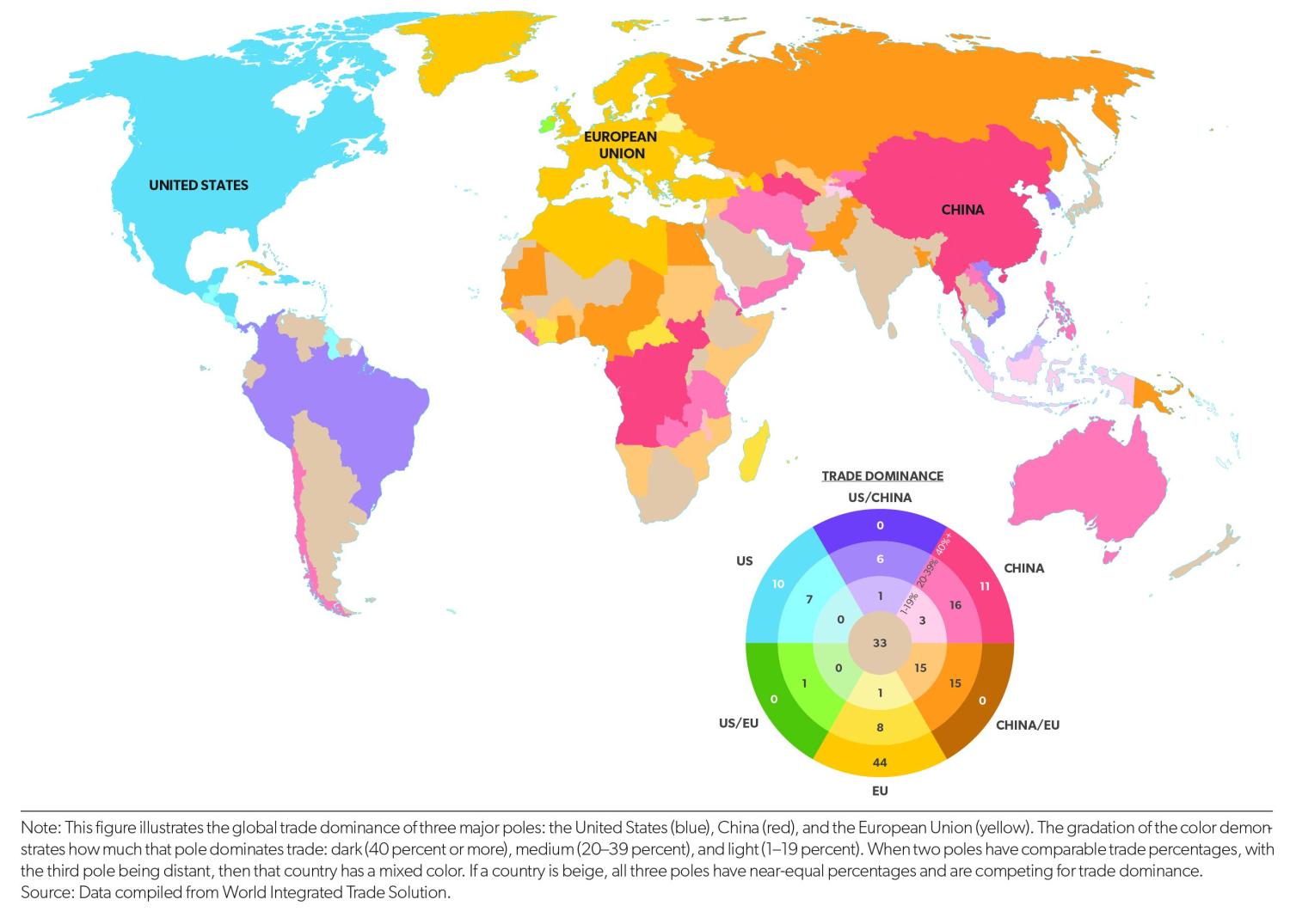

Source: American Enterprise Institute

The economic agenda

The U.S.-Europe economic agenda on China should focus on three priority areas. First should be coordinating responses to protect against China’s industrial overcapacity, which is hollowing out manufacturing on both sides of the Atlantic. Washington and Brussels should establish a shared set of metrics for judging overcapacity across sectors and aligning their actions as appropriate. Otherwise, officials risk simply redirecting Chinese overcapacity from one side of the Atlantic to the other in a never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

A second economic priority should be synchronizing export controls. Many of these efforts are bilateral between Washington and individual European capitals—such as American and Dutch restrictions on Chinese access to ultraviolet lithography machines and maintenance. Yet, given the strategic nature of these decisions, and China’s increasingly concerning use of its own export controls, the United States and Europe will need to develop a common set of policies. Full decoupling should not be the objective, but rather targeted derisking and protective measures in dual-use areas ranging from semiconductors to biotechnology and quantum computing.

The third economic priority should be supply chain security, particularly around rare earths. China’s dominance of many rare earth mining and production processes presents a serious threat to both the United States and Europe. The scale of the investment challenge in rare earths is substantial, so it is best addressed through combined cooperation by a variety of countries. Europe and the United States should look to work with leaders in Canada, Australia, and other countries that can help alleviate this chokepoint. Establishing attractive offtake agreements will be critical to incentivize companies to invest in ways that will ultimately reduce supply chain vulnerabilities.

This shared economic agenda should form the basis for coordination not only between the United States and the European Union, but also with other leading democracies. The G7 will remain a vital forum for alignment among advanced industrial democracies, including Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom. But agreement with South Korea, Australia, and others who are not members of the G7 is also critical, so they should be included consistently as G7 observers to ensure that the United States and Europe are maximizing the effectiveness of China-related policy coordination.

The security agenda

Although cooperation on security issues will prove more challenging than on economic ones, there are still some discrete areas in which policy alignment should be possible. To the extent that China becomes more active in the Euro-Atlantic area, there may be potential for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to develop a coherent approach. For now, most China-related security cooperation is likely to occur outside the NATO framework. China’s support for Russia’s war in Ukraine is likely to be the primary China-related security concern for many across Europe. Coordinating ways to dissuade Beijing from supporting Moscow, whether through diplomatic actions or economic threats, could remain a high priority as long as the war continues. That depends, of course, on whether the Trump administration is willing to oppose Russia’s war and take actions that would impede China’s support.

The most attractive near-term possibility should be a major defense industrial production initiative. There are a number of defense production efforts involving the United States, Europe, and Asian partners, but they cannot match China’s scale without a super-sized effort designed to dramatically increase production capacity and drive down the price of individual systems. An allied arsenal program of this sort could initially focus on munitions coproduction but might also expand over time to include larger and more complex platforms.

Cooperation on military operations vis-à-vis China is likely to be more limited than that on defense production. For the time being, it is likely that U.S. defense cooperation on China will continue to focus on a handful of European states. This will probably include France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, all of which have engaged actively in the Indo-Pacific. They should continue to coordinate with Washington on military deployments across the Indo-Pacific, particularly their naval deployments in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, despite the opposition to these efforts from some in the Trump administration. In doing so, they should make clear to U.S. leaders that they conduct these missions out of their own national interest, not at the direction or discouragement of the United States.

Finally, the United States and the European Commission should try to maintain some degree of strategic alignment on China policy. They should look to issue a joint statement outlining the key elements of their China policies. Since the Trump administration’s China approach is driven from the top down, the value of meetings below the cabinet level will be limited. And yet, discussing China strategy with Trump directly is unlikely to be productive. As a result, leaders in Washington and Brussels should continue to hold regular China strategy meetings, but for these to be impactful, they may need to be led by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas.

Conclusion

There is a real risk that the United States and Europe will become increasingly disconnected on China strategy in the years ahead. Discord between Washington, Brussels, and other European capitals—plus the unfortunate reality that the second Trump administration does not have a unified China strategy—will impede efforts at cooperation. Nonetheless, aligning transatlantic policies toward China remains critical. In this long-term systemic competition, it is vital that the United States and Europe show that democracies can deliver results at home and public goods abroad. Although they may differ on specifics, countries on both sides of the Atlantic share an overall goal in this regard.

This essay suggests that cooperation between the United States and Europe is likely to be issue-based, episodic, economically focused, and increasingly guarded. But this does not mean that policy alignment is impossible, just more difficult. The United States and Europe are likely to cooperate most deeply in responding to China’s economic behavior, since Beijing’s non-market practices are a serious threat to the U.S. and European manufacturing bases. But security cooperation should also be possible in certain, more limited, areas. The recommendations made here are not intended to obscure the scale of the challenge that lies ahead, but rather to highlight what can be done despite these challenges.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How should the United States cooperate with Europe on China strategy?

December 5, 2025