Is the annual expenditure on U.S. public elementary and secondary education appropriate and sustainable? Reasonable people can disagree whether the current $600+ billion—5.2 percent of the nation’s GDP—is too much or not enough, especially when considering the different federal, state, and local jurisdictions involved. However, there are increasing signs that it is likely not sustainable at its present, relatively low level of productivity.

In this era of middling economic performance and constrained government resources, new thinking about how we fund public education is critical. The current system is opaque by allocating revenue almost entirely upon student attendance or enrollment, which misaligns incentives for improving outcomes.

Performance-based funding

An alternative funding model gaining traction in several states is worth including among other education reform topics. Performance-based funding (PBF) is a method of funding social programs—including education—in which public resources are directed to approaches that produce better outcomes.

Currently, government budgets are almost exclusively designed to pay for inputs rather than achieving outcomes. PBF can provide a new approach to improving educational outcomes beyond current practice, while addressing systemic inefficiency. PBF has gained traction in higher education, and merits some discussion of whether it can improve K-12 education.

A number of states have been implementing PBF for various programs over the last several years, and now the federal government is following their lead. In fact, the recently enacted Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, includes significant innovation in two “pay-for-success” authorities (in the U.S., “pay-for-success” contracts refer to a particular type of PBF called social impact bonds, described further below).

Pay-for-success is included as an option to fund activities under Title I, Part D, which addresses the education of neglected and delinquent students, and also in a provision of Title IV. (See https://www.congress.gov/114/bills/s1177/BILLS-114s1177enr.xml; search for “pay for success.”) These provisions are closely modeled on a bipartisan proposal originally put forward by Senators Hatch (R-Utah) and Bennet (D-Colo.).

Collectively, the combined funding for these two authorities enables over $300 million to potentially be used for innovative PBF initiatives (subject to appropriations, of course). Though these provisions are tucked in relatively small programs of ESSA, they nonetheless represent a watershed by their inclusion in the most prominent piece of new federal education legislation passed in many years.

Social impact bonds

These federal provisions are a step toward upending traditional funding practices, and could spread to other programs and funding streams, including at the state level. Utah and Chicago already utilize performance-based funding models called social impact bonds. Colorado also recently authorized the use of social bonds for initiatives that help promote child and youth development. Just this week, Connecticut and South Carolina announced significant new social impact bond initiatives of their own for public health programs.

Social impact bonds are set up to direct public funding to those institutions and programs that are clearly demonstrating their impact through rigorous results, thereby mitigating financial risk to the taxpayer, and providing an effective means for state and local governments to scale up successful innovations.

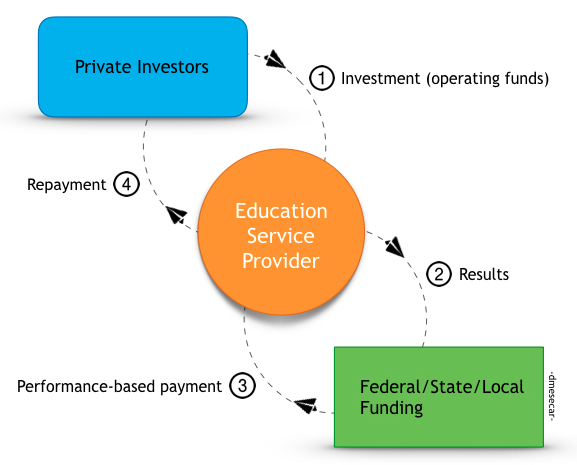

In a typical arrangement, a service provider gets operating funds by raising capital from private or philanthropic investors. These investors have the opportunity to earn both social and financial returns while putting their capital to work in service of society. The state government contracts with the service provider (which could be a school or non-governmental organization) to provide services, and only pays the service provider based on the achievement of defined performance targets. (For more information on social impact bond models, see the Non Profit Finance Fund’s Pay for Success Learning Hub and this Brookings report on the potential and limitations of impact bonds.)

Figure 1. Example of a social impact bond model

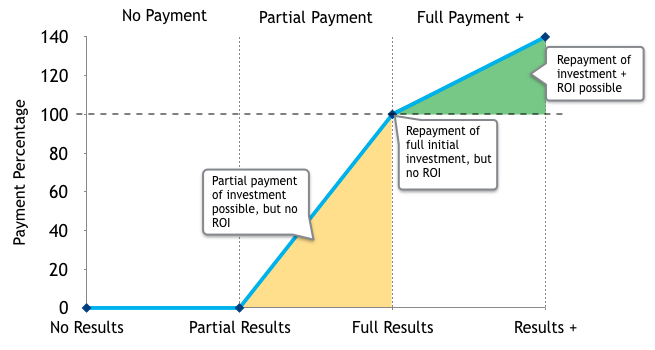

If the service provider fails to achieve the performance targets, the government does not pay. Payments can increase for performance that exceeds the expected outcomes, up to a predetermined maximum, which in turn pays back the original investment as well as any pre-determined return on that investment (ROI).

Figure 2. Relationship of results to payments for social impact bonds

State experimentation

Other state-based PBF models are developing a more extensive track record. Arizona began a statewide PBF program in 2013, called “Student Success Funding,” which expanded in 2014. Likewise, Michigan has been implementing a limited model since 2012. Pennsylvania took a slightly different approach, providing funding flexibility in exchange for performance-based outcomes. And Florida has had a long-standing funding model tied to its A-F grading system that provides additional funding based on student outcomes.

These different approaches to PBF share the notion that public funding should go to those programs that are clearly demonstrating their impact through rigorous, outcome-based performance measures. There certainly are tradeoffs for pursuing PBF models, such as directing funding away from established, though less easily measured, programs; requiring new methods of oversight from governmental entities; or experiencing unproductive programs. On balance, though, PBF can provide an effective launching pad for scaling initiatives and innovations that produce measurable results.

Looking to the future

Not every PBF program will be designed optimally or deliver anticipated, specific outcomes. The question is not whether we can afford to undertake innovative new approaches, but whether we can afford not to.

Over time, PBF can better align critical education funding with important outcomes to incent ongoing, improved performance of schools individually and systemically, with models which can be replicated in other jurisdictions. It provides an opportunity to make strategic investments in schools by a straightforward focusing of school funding on desired results.

Perhaps, as decision makers at all levels of government face increasingly difficult budget processes, more states will follow the lead of their peers in federal and state government by experimenting with and adopting more performance-based funding initiatives.

Editor’s Note: This post was updated for clarification. Also, on February 29, 2016, from 9:30 AM – 3:30 PM EST, the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings will host a live event and webcast on the global potential and limitations of impact bonds.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).