On December 9, 2025, the Department of Education announced it agreed to a settlement to end the case brought by the state of Missouri against the SAVE plan. This proposed settlement requires borrowers in all of the ICR based plans to transition to IBR or RAP. As of writing this, it is still unclear when the settlement is expected to be approved by the court or how the transition will be handled.

OBBBA was passed into law in July 2025. In that same month, the Department of Education established two negotiated rulemaking committees to discuss drafts of proposed regulations to implement the changes by the OBBBA. In November, the committees concluded the negotiated rulemaking sessions and in January of 2026, the consensus language was published in the Federal Register as a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking. The public comment period ended on March 2, 2026. (March 4, 2026)

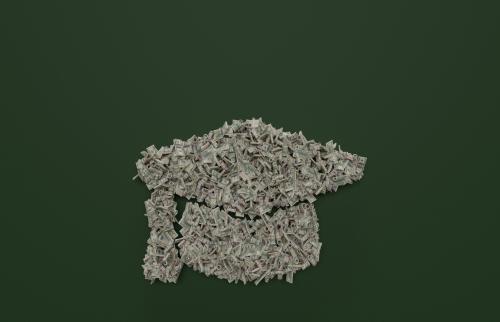

This document provides a detailed overview of how the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA)—passed into law in the summer of 2025 and set to take effect in just a few short months—changed higher education financing. It describes the state of student lending at the time of its passage, analyzes how the law changes borrowing, repayment, and institutional accountability, and explores some key implications for students, families, and the federal budget.

In 2025, about 43 million Americans owed more than $1.6 trillion in federal student debt. Following the end of the pandemic-era payment freeze in October 2023, and further temporary protections over the year that followed, delinquencies and defaults surged. By then, borrowers were enrolled in a variety of repayment plans, including several million borrowers left frozen in administrative forbearance.

OBBBA enacted several major reforms:

- Borrowing caps: The act imposes limits on parent loans and most graduate loans, with higher limits for professional degree programs. These limits will affect roughly 25–40% of graduate borrowers, reducing federal loan volume by $8–10 billion annually once fully phased in, and reducing total government outlays by $44 billion over 10 years. The impact falls most heavily on longer or higher-cost master’s and professional programs, particularly in health-related fields.

- Repayment reform: Beginning in 2026, all new borrowers will choose between a single fixed “tiered standard” plan and a new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP). RAP replaces multiple income-driven repayment (IDR) options with one structure that ties payments to total adjusted gross income rather than discretionary income. In terms of payment amounts, RAP shares some similarities with the Obama-era Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) plan, but requires all borrowers to make some payment even at the lowest income levels and extends repayment to 30 years, which increases total payments and lowers long-term government subsidy costs. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates RAP will save $271 billion over 10 years. Borrowers on older income-driven repayment plans (including REPAYE) must transition to certain legacy income-based repayment or other existing plans or to RAP by 2028.

- Institutional accountability: A new “do no harm” standard links federal loan eligibility to graduates’ median earnings after completion. Programs whose graduates earn less than the typical high school graduate (or bachelor’s degree-holder, for graduate programs) risk losing access to student loans. Only about 1.8% of students—mainly in certificate or for-profit programs—are expected to be affected, while most public and nonprofit institutions easily meet the standard.

Economic effects: OBBBA’s reforms may moderate student debt growth and shift repayment risk toward borrowers but are unlikely to impose major short-term macroeconomic shocks; the major economic adjustment already occurred with the 2023–2025 repayment restart, which reduced consumer spending and credit scores as millions resumed payments. In contrast, OBBBA’s borrowing caps and new repayment rules will affect future borrowing and repayment more gradually over many years.

What to look for next: Implementation will help determine OBBBA’s effects. Regulations will determine how certain legislative changes are applied. Servicers must retool operational systems to implement RAP by July 2026, with open questions about how quickly existing borrowers can migrate. The effects of federal loan caps will depend on how institutions respond to borrowing limits and whether private lenders will fill the gap, or whether some students will be priced out of advanced degrees. And future administrations could delay or reinterpret major provisions, such as borrower defense rules or accountability enforcement.

The state of student lending prior to OBBBA

Before the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the federal student loan portfolio was enormous and under stress. Roughly 43 million Americans owed a combined $1.6 trillion in federal student debt. About 35 million borrowers were supposed to be in repayment (the others were still in school, in their grace period, or in deferment), but after years without required payments, many were struggling: In the third quarter of 2025, 5 million borrowers were in default and another 7 million were behind on their payments. In addition, another 10 million borrowers were in forbearance (no payments due, no interest accruing)—mostly due to legal challenges that halted implementation of the recently created SAVE repayment plan.

During the pandemic, the Biden administration used executive action to forgive or discharge nearly $189 billion in loans through targeted initiatives like Public Service Loan Forgiveness fixes, income-driven repayment (IDR) adjustments, and borrower defense claims. Despite these record discharges, the overall stock of debt kept climbing as new loan originations outpaced forgiveness and (voluntary) repayments.

From March 2020 through September 2023, most federal loans were placed in interest-free forbearance. Payments formally restarted in October 2023, but a temporary “on-ramp” shielded borrowers from credit-reporting consequences through late 2024. That shield lifted in the first quarter 2025, and delinquencies quickly hit millions of borrowers’ credit reports, affecting their credit scores.

Before Trump took office for his second term, most student loan repayments and credit reporting had already restarted. The Trump administration announced an intention to increase collections and to accelerate the resumption of repayment but has been slow to do so. For example, despite the Department of Education’s announced plans to restart more aggressive methods of collecting overdue loan payments, like withholding tax refunds or garnishing wages, refund offsets did not begin until after the current tax season and the Department of Education announced that wage garnishment would restart in January. Subsequently, the administration recently announced a suspension of all collections.

In 2019, the Treasury reported $70 billion in student loan repayments, but that fell to $28 billion in 2022 and $27 billion in 2023 because of the pandemic forbearance. After the resumption of repayment in fiscal year 2024, payments rebounded to $60 billion and in 2025 hit $62 billion. One reason payments did not return to their pre-pandemic level is that the roughly 8 million borrowers who signed up for the Biden-era Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) program have been placed into forbearance due to legal action against that plan, which the Department of Education recently agreed via a court settlement to formally wind down in 2026.

In short, before the passage of OBBBA, steps to normalize the student loan repayment system after the pandemic—restarting payments and credit reporting—had been taken. Still, it was far from fully restored, and important long-standing structural problems remain unresolved.

A reminder: Who borrows and for what?

Federal loans are broadly accessible: Any U.S. student enrolled at one of roughly 6,000 accredited institutions—from flagship public universities to community colleges, private nonprofits, and for-profits—is eligible. There are almost no underwriting standards or credit checks.1 Any student enrolled at least half-time can borrow up to their annual loan limits or the cost of attendance, whichever is lower.

For undergraduates, those limits have not been adjusted in years and are quite low—just $5,500 for first-year, dependent students. But parents and graduate students have effectively faced no borrowing limit for the past two decades. This asymmetry in limits helps explain a striking imbalance: While graduate students make up only 17% of enrollment, they account for nearly half of all new federal lending.

In 2025, the Department of Education expected to originate about $90 billion in new loans: 38% to undergraduates, 49% to graduate students, and 12% to parents of undergrads.2 In part because graduate and professional loan borrowers have faced virtually no federal loan limits, their per-student debt burdens have ballooned. In 2020, the average master’s degree completer left school with $62,820 in debt, up 50% since 2000. For professional programs such as law and medicine, the average debt load reached $197,750, an 80% increase over two decades (National Postsecondary Student Aid Study).

Loans can be used not just for tuition, but also for living expenses. Roughly a third of graduate borrowing and two-thirds of Parent PLUS borrowing for undergraduate students is used to pay for non-tuition costs (like rent and food) (National Postsecondary Student Aid Study 2020). In that sense, some of this lending is more similar to unsecured consumer credit than to loans used to finance human capital (and that portion of forgiven loans is similar to a cash transfer).

Repayment landscape and borrowing outcomes

Borrowers today face two broad paths for repaying their loans: the standard fixed plan and income-driven repayment (IDR) plans in which payments are based on borrowers’ income.3 By early 2025, about 60% of borrowers had enrolled in IDR plans (especially the SAVE plan, before it was frozen by litigation), while others remained on fixed schedules (Department of Education, Federal Student Aid Data Center 2025). The diversity of plans and terms is one reason repayment outcomes vary across borrowers.

Research about student loan borrowers suggests that loan outcomes like default largely reflect borrower characteristics and institutional context. The system lends to all students on nearly identical terms, but students attend very different schools, with varied resources, programs, and career pipelines. Those differences show up in financial outcomes like loan repayment and default rates.

For similar reasons, the amount of debt owed by a borrower can be a misleading indication of financial hardship. Paradoxically, the borrowers with the largest balances have better repayment outcomes than those with lower balances, on average. This is because they are often the most educated—lawyers, doctors, MBAs—and typically earn enough to manage their debts. Conversely, those with smaller debts often struggle the most, reflecting weaker labor market outcomes, lower completion rates, or enrollment at institutions with poor returns.

How the One Big Beautiful Bill Act changes student lending

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) represents the most significant rewrite of federal student aid in years and reshapes who can borrow, how much, and on what terms.

Caps on borrowing

OBBBA places new limits on graduate and parent borrowing. Parent PLUS loans will be capped at $20,000 per year and $65,000 lifetime per dependent student. Graduate students, who currently account for about half of new federal lending annually, will also face new ceilings: Most programs are capped at $20,500 annually with a $100,000 aggregate maximum, while students in professional programs such as law and medicine may borrow up to $50,000 annually and $200,000 in aggregate. For the one-third of graduate students who attend part-time, these limits would be prorated.

These changes are scheduled to take effect for the 2026–2027 academic year (starting July 1, 2026). Existing borrowers enrolled in an institution of higher education prior to that date will be allowed to borrow under the old limits for three years or until they complete their current program (whichever comes first), except that part-time students’ loans will still be prorated beginning this year. The Congressional Budget Office expects loan limits to reduce the cost of graduate loans by $44 billion over 10 years. A sizable share of graduate borrowers will be affected by these limits. On an annual basis, about 26% of graduate students currently borrow above the new annual caps. Looking at students who are completing a degree, about 40% have cumulative debt that exceeds the cumulative graduate limit.4 That corresponds to roughly 370,000 graduate and professional students (of 3.6 million graduate-level students and 1.4 million federal borrowers in a given year) or about 200,000 students completing a degree (of 1.1 million completers, of whom 500,000 borrowed). Across all graduate fields, this corresponds to roughly $8 billion in annual federal lending that would no longer be disbursed once the caps take effect. Accounting for pro-rated loan limits for graduate students could bring the number affected to more than 500,000 borrowers, with over $10 billion in federal loans currently above the cap.

The share of graduate borrowers impacted by the new limits varies by credential level and field. At the credential level, about 41% of master’s degree recipients who borrowed and 27% of professional student borrowers exceed the new lifetime limits. (In 2020, about 344,000 master’s degree recipients—48% of all such degree recipients—and 93,000 professional degree recipients—75%— borrowed federal loans.) Most of the reduced loan eligibility due to the new caps will come from their impact on master’s programs, accounting for nearly $6 billion (out of $10 billion) of the total federal loan volume above the new caps. Borrowing above the cap is highest among students in longer or higher-cost programs. Master’s degree students in STEM and health disciplines5 represent a large share of affected borrowers, reflecting both longer program durations and higher tuition. Additionally, professional degrees such as law and medicine and other health related fields are particularly affected. Among law students, for instance, about one-third borrow above the new lifetime limit, resulting in an estimated $560 million annually in curtailed federal disbursements.

By contrast, shorter graduate certificates and post-baccalaureate programs will be less affected by the caps—only about 19,000 completers in these programs borrow above the new thresholds—but they still account for roughly $600 million in borrowing above the new caps. This is because these programs often serve older or part-time students, often with prior graduate debt. Overall, the incidence of OBBBA’s borrowing caps is highly concentrated: The majority of graduate students borrow below the limits, but those in high-tuition, multi-year, or professional programs would encounter meaningful shortfalls in available federal credit.

Repayment reform

The second important set of higher education policies in OBBBA are provisions to streamline repayment plans. Students who first borrow on or after July 1, 2026 will be offered only two options when they enter repayment: a new “tiered standard” plan, with repayment term lengths that vary by balance, and a single new income-driven option called the Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP). Some legacy plans—Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR), Pay As You Earn (PAYE), Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE), and SAVE—will remain available temporarily only for loans originated before that date, and borrowers on those plans must choose to move to Income-Based Repayment (another income-driven plan), RAP, or a fixed payment plan by 2028. Borrowers in legacy plans who do not choose a repayment plan will be automatically enrolled in RAP. (In contrast, borrowers enrolled in the Income-Based Repayment plans or one of the current fixed repayment plans can remain in those plans after 2028.)

Currently, borrowers in the standard plan repay over 10 years. Under the new tiered standard plan, the term of repayment will be longer for borrowers with larger initial balances. The plan requires fixed monthly payments for 10, 15, 20, or 25 years, depending on the borrower’s total loan balance.6 Because this structure makes lower monthly payments (over a longer term) available to high balance borrowers, income-based repayment plans (including RAP) will be less desirable for borrowers with large initial balances than they would have been when the only fixed-payment alternative was a 10-year standard plan, especially if their incomes are also higher.

The new Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP) is best understood as a successor to existing plans like PAYE or REPAYE rather than a wholesale redesign. Like prior IDR plans, RAP ties monthly payments to income and offers forgiveness after a specified number of years, making it more affordable than the fixed standard plan for many borrowers.

Figure 1 shows that annual payment burdens under RAP and REPAYE are nearly identical for middle-income borrowers but diverge at the edges: Payments rise more steeply for high earners and low-income borrowers must pay at least $10. Under REPAYE, borrowers pay 10% of their discretionary income—defined as earnings above 150% of the federal poverty line for their household size—with no minimum payment, so borrowers with very low incomes often owed nothing. RAP replaces this discretionary-income framework with a tiered schedule based on total adjusted gross income (AGI). Borrowers pay 1% of AGI between $10,000 and $20,000; 2 percent between $20,000 and $30,000; and so on, increasing by one percentage point for each additional $10,000 of income until reaching a maximum of 10% for incomes above $100,000. Every borrower must make at least a $10 monthly payment, regardless of income, and receives a $600 annual reduction in required payments for each dependent child. The relationship between income and student loan payments under RAP compared to REPAYE is shown in the figure below.

Borrowers with similar incomes face similar payment obligations in RAP and REPAYE. Very low-income borrowers who previously qualified for $0 payments under REPAYE will now owe small fixed amounts, middle-income borrowers—roughly those earning $40,000 to $60,000 AGI—will often see somewhat lower payments than under REPAYE’s flat 10% rule, and high-income borrowers (above $80,000–$100,000) will generally pay more, since RAP’s 10% rate applies to their entire income rather than only income above a poverty threshold.

RAP also embeds two implicit subsidies that ensure balances decline over time for borrowers who make their monthly payments on time. First, any unpaid interest in a given month is automatically waived—ensuring that balances do not grow when required payments are less than interest accrued. Second, RAP introduces a “principal subsidy”: the first $50 of a scheduled payment is credited toward reducing the loan’s principal (even if the payment does not cover the accrued interest). For example, if a borrower pays $25 but accrues $75 in interest, the borrower’s principal balance is reduced by $25 and the unpaid interest is forgiven. Together, these provisions mean that borrowers who make on-time payments will see their loan balance decline each month, even when their payments are small.

Simulations in a recent PEER Center Report “indicate that borrowers with modest incomes and small balances—such as those owing around $12,000 to $15,000—can become debt-free somewhat faster in RAP than under REPAYE due to the $50 monthly principal subsidy, whereas borrowers with larger debts or persistently low earnings will remain in repayment for much longer—up to the full 30-year term compared with 20–25 years under prior plans.

The key parameters of RAP are not indexed to inflation, meaning that over time, rising nominal incomes will push borrowers into higher payment brackets even if their real purchasing power remains unchanged. In particular, the income tiers, $600 per-child dependent discounts, and $50 principal subsidy are all fixed in nominal terms.

Balances remaining after 30 years of qualifying payments are forgiven, extending the repayment horizon relative to prior IDR plans (for example, 20 years for undergraduate and 25 years for graduate borrowers under REPAYE). Modeling of lifetime repayment outcomes shows that RAP will increase total payments and reduce effective subsidies for most low- and moderate-income borrowers relative to prior income-driven plans. Borrowers starting with annual incomes below about $40,000 repay a larger share of their original balances because they no longer qualify for $0 payments and must remain in repayment for up to 30 years rather than 20 or 25. For such a borrower, total lifetime payments will be notably higher compared to REPAYE, even after accounting for RAP’s interest and principal subsidies. Borrowers with moderate incomes—roughly $50,000 to $70,000 when they enter repayment—will typically repay their loans in full within 13 to 15 years, with lifetime payments similar to or slightly lower than under REPAYE. For high-income borrowers, total payments are roughly unchanged or modestly higher, reflecting the 10% rate applied to full income rather than income above a threshold.

RAP’s structure standardizes repayment parameters across all borrowers and replaces multiple income-driven repayment options with a single formula that links payments to total income, eliminates negative interest amortization, and provides a guaranteed pathway to forgiveness after three decades of consistent repayment. Compared to repayment options available when OBBBA was passed (including the SAVE plan), these changes will reduce the government’s effective subsidy per dollar lent by increasing the repayment horizon and increasing monthly payments. The result is a system that recovers more of the government’s original lending costs and reduces average loan forgiveness, especially among borrowers with low incomes or modest debts.

OBBBA did not alter the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program directly. However, changes to repayment plans and loan limits will indirectly affect which borrowers benefit from PSLF. Whereas qualifying borrowers today can make payments that count toward PSLF on either income-driven or the 10-year Standard Plan, payments on the new tiered Standard Plan will not count towards PSLF forgiveness. New borrowers will have to be enrolled in RAP to earn credit toward PSLF. Because RAP will require higher payments for some would-be PSLF borrowers, especially higher-income borrowers, forgiveness will be smaller. Additionally, because RAP reduces unpaid interest accumulation and increases required payments for many middle- and high-income borrowers, some PSLF borrowers will, on average, have smaller remaining balances after 10 years of qualifying payments (when PSLF forgiveness occurs). In that sense, RAP narrows the gap between public- and private-sector borrowers’ repayment profiles, reducing implicit federal costs associated with PSLF while leaving its eligibility rules and 10-year forgiveness period unchanged.

The Congressional Budget Office expects RAP to reduce the cost of the federal loan program by $271 billion over 10 years. Of that, $150 billion is from higher repayments among existing borrowers, while the rest comes from higher repayments among borrowers taking new loans over the next decade. A large share of these savings arises from eliminating the SAVE program.

Importantly, these savings reflect accounting on a net-present-value basis. Much of the projected savings arises from stretching repayment out to 30 years, which increases the government’s expected interest and principal collections. Hence, the large apparent budgetary savings are not representative of the near-term impact on borrowers’ repayments.

The law makes other, smaller changes to loan repayment, too. It eliminates common deferment categories—such as economic hardship and unemployment—and caps the use of long-term forbearances. It also gives borrowers in default two opportunities (rather than one) to rehabilitate their loans, increasing the minimum payment for rehabilitation from $5 per month to $10.

Other notable provisions in OBBBA

Although the student loan borrowing caps and repayment reform have garnered the most attention, OBBBA makes important changes to Pell Grants and creates new accountability rules as well. The law creates a new “Workforce Pell” grant program for very short-term programs (8–15 weeks7) aimed at career-oriented training. At the same time, the law tightens Pell Grant eligibility slightly by excluding students already receiving full scholarships or those from families with more significant wealth. It also appropriates $10 billion to close a Pell shortfall that the program was already running for fiscal year 2026.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act also establishes a new federal accountability framework—referred to as the “do no harm” standard—that will condition student loan eligibility for most higher education programs on the post-graduation earnings of their former students. The framework marks the first time Congress has directly linked broad student-loan eligibility to verified post-college earnings outcomes.

Under this rule, undergraduate associate and bachelor’s degree programs must show that their graduates’ median earnings four years after completion exceed those of typical 25- to 34-year-olds with only a high school diploma who are employed and not enrolled in school. The comparison group is defined at the state level if most of a college’s students are in-state or at the national level if the institution enrolls a primarily out-of-state population. In 2019-dollar terms, these thresholds ranged from about $21,600 in Mississippi to $31,961 in North Dakota, with a national median of roughly $26,000.

For graduate programs—including master’s, doctoral, and graduate certificate programs—the benchmark is tied to the median earnings of bachelor’s-degree holders aged 25–34. The Department of Education applies the lowest of three relevant medians for colleges with a primarily in-state population: (1) all bachelor’s-degree holders in the same state, (2) bachelor’s-degree holders in the same field of study within that state, or (3) bachelor’s-degree holders nationwide in that field. For colleges with a primarily out-of-state population, the comparison group is the lower of all bachelor’s degree-holders or in that field of study nationally. This formula introduces leniency for programs in low-wage fields or states by using the lowest available threshold.

Programs whose graduates fail to earn above the applicable threshold in two of three consecutive years will lose eligibility for federal student loans for at least two years, though they may retain access to Pell Grants and other aid. Colleges can appeal before losing eligibility. Notably, undergraduate certificate programs are explicitly exempt from this statutory test, even though they often produce the weakest labor-market outcomes. These programs remain subject instead to the separate Gainful Employment regulations, which were finalized in 2023 to apply a similar high school earnings threshold and debt-to-earnings standard to non-degree (certificate) and for-profit programs. The Trump administration has indicated it plans to re-regulate to exactly match the standard in OBBBA, providing the same earnings premium-based accountability for all programs under one or both of those legal authorities.

Analysis by the Postsecondary Education and Economics Research (PEER) Center suggests that expected incidence of sanctions is small. Among the programs covered by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act’s accountability provisions—that is, associate, bachelor’s, graduate certificate, master’s, doctoral, and professional programs— only about 1.8% of all students are enrolled in programs whose graduates earn less than the applicable OBBBA threshold that would cause them to lose access to federal student loans. The majority of at-risk enrollment is concentrated in undergraduate certificate programs. However, accounting only for the programs included in the OBBBA accountability framework, associate degree programs account for roughly 60% of students in failing programs, followed by bachelor’s programs (16%) and graduate programs (24%). Graduate programs most likely to fall below the threshold are in lower-paying fields such as the arts, alternative medicine, and certain health services. By contrast, most programs in business, engineering, education, and other high-earning fields comfortably exceed the standard.

PEER analysis also shows that institutional exposure to potential sanctions for not meeting the earnings threshold is also uneven. The for-profit sector accounts for a disproportionate share of programs at risk, even after excluding certificate programs. About 4.9% of students at for-profit colleges are in degree or graduate certificate programs that fail the OBBBA earnings test, compared with only 1.7% of students at public and nonprofit institutions. Nearly all public and nonprofit colleges have very few or no failing programs—roughly three-quarters have none, and more than 90% have fewer than 10% of their students in programs below the threshold. The colleges most affected tend to be small, two-year, for-profit institutions concentrated in vocational or career-oriented fields. In contrast, most four-year colleges, including Historically Black Colleges and Universities and minority-serving and rural institutions, have little or no exposure under the new rule.

Note that undergraduate certificate programs are exempt from the OBBBA accountability test but would be substantially impacted if they were included. These programs enroll only about 8% of federally aided students yet account for more than half of all enrollment in low-earning programs. Roughly one in four undergraduate certificate students are enrolled in programs that would fall below the “do no harm” threshold, and most of these programs are in the for-profit sector—especially cosmetology and allied health fields—where typical graduate earnings are roughly $10,000 lower than comparable programs at public or nonprofit institutions. Including these programs in the accountability framework would increase the overall failure rate from about 1.8% to roughly 3.7% of all students, dramatically expanding the number of programs subject to potential loan ineligibility.

Other debt relief

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act also reshaped federal loan relief outside of repayment by changing the rules for borrower defense to repayment and closed school discharges. Under the Biden administration, these programs had been expanded with the goal of providing relatively quick and generous relief for students who were misled by their institutions or whose schools shut down. OBBBA delays the implementation of those Biden-era rules until July 2035, effectively reinstating the narrower Trump-era standards in the meantime (and providing ample time for the Education Department to issue new regulations, if it so chooses). That shift significantly restricts near-term access to these discharges, making it harder for borrowers to have debts canceled on the grounds of institutional misconduct or school closure. The delay reflects the law’s broader tilt away from ad hoc loan forgiveness toward tighter eligibility and longer repayment commitments.

Expected economic impacts and uncertainties

Private lending

One open question is whether the new federal loan limits will push affected families into the private credit market. The likelihood of substitution is most acute for graduate and professional students, who have long relied on uncapped federal lending, and for families using large Parent PLUS loans.

But private loans come with stricter underwriting, higher interest rates, and limited borrower protections. As a result, observers expect only partial substitution: Some high-credit-score borrowers may pivot to private lenders, but many others will face tighter borrowing constraints, especially in fields with weaker expected earnings, and may seek out lower-cost programs or abandon their pursuit of higher education altogether.

Economic impacts on borrowers and households

The economic effects of student lending policy should be understood as modest in scale, especially compared to the much larger shock of repayment restarting in 2023–2025. That adjustment was the major event; subsequent policy changes mainly fine-tune the repayment landscape rather than introduce new cash-flow shocks.

Research from the Federal Reserve shows that when payments resumed in October 2023, consumer spending dipped, particularly among households that had to start making student loan payments. The Federal Reserve’s analysis of the payment restart suggests a sharp reduction in household spending—on the order of $130 per month for resuming borrowers—but that estimate looks surprisingly large when set against the aggregate data. Federal borrowers were repaying about $70 billion annually before the pandemic, which fell to roughly $27 billion during the pause and has since rebounded to around $60 billion in both FY 2024 and FY 2025. That means the restart raised payments by about $33 billion relative to the pause, not by $60–80 billion. Earlier analysis of the entry into the repayment pause, from comparing affected and unaffected borrowers, also found smaller effects: For an average paused payment of $149/month, spending rose by just $60/month—roughly one-third of the foregone payment. Those findings, along with survey evidence from the New York Fed, suggest that the restart’s macroeconomic impact was real but modest and that the Fed’s headline estimates may overstate the scale of the consumption shock.

Similarly, the return of delinquencies to credit files in early 2025 had a noticeable but largely one-off impact on household credit scores and mortgage eligibility. Millions of borrowers saw their credit scores drop, pushing some out of the conventional mortgage market. But this shift was the result of the “on-ramp” expiring, not of the OBBBA reforms, which have yet to take effect. Going forward, student loan delinquencies will continue to be a drag, but they are unlikely to be a new or escalating macroeconomic force.

The borrowing caps in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act may slightly constrain tuition-driven debt growth, but those effects will phase in gradually and are small relative to the size of the federal loan portfolio. Institutions that previously relied heavily on unlimited Parent PLUS or graduate lending may adjust pricing or enrollment strategies, but these changes are incremental. In short, most of the big macroeconomic adjustments—reduced household spending and deteriorating credit profiles—have already happened through separate policy decisions made over the last several years. OBBBA’s reforms will shape the system’s structure over the long term, but their near-term transmission to the broader economy is limited.

What to watch next

The details of implementation remain unsettled, and those details will shape how the law works in practice.

One major uncertainty involves whether and how undergraduate certificate programs will be subject to any accountability rules. The statute does not apply accountability policies for these programs (despite 24% of their students enrolled in programs that would have failed).A rulemaking process in January 2026 suggested the Department intends to apply the same accountability to those programs under the separate gainful employment authority, but the regulations remain pending.

Another gray area was the definition of a “professional degree program” for the purpose of administrating new loan limits for graduate borrowers. The law references existing regulatory language, but the definition the law relies on is both vague and oddly constructed. It includes classic professional pathways like medicine, law, pharmacy, and veterinary science but also reaches into fields such as chiropractic and theology. The Trump administration recently agreed to proposed regulations that would use those fields as professional degrees, plus clinical psychology degrees. However, the rules remain pending, and there are bipartisan legislative efforts to broaden the definition of professional degrees underway.

Beyond definitional issues, several broader questions remain. Will private lenders step in to fill the gap left by capped federal credit, and at what cost to borrowers? How quickly will RAP be implemented—the law sets a July 2026 deadline, but how quickly the repayment system can be migrated and how ready loan servicers are to make the transition are open questions. How steep will the rise in delinquencies and defaults be once collections are fully underway, in particular among low-income borrowers subject to the new RAP plan’s minimum payment amount? And how will rising interest rates affect the affordability of borrowing for new cohorts, especially in high-cost graduate fields?

Finally, there is political uncertainty. Even with OBBBA enacted, it is not clear how aggressively the Trump administration will implement provisions that might prove unpopular with institutions or borrowers, or burdensome to a Department of Education that has been reduced to about half its prior staffing. Some elements could be delayed, narrowed through regulation, or deprioritized altogether. Moreover, if Congress changes political hands in the coming years, policymakers might seek to alter or reverse some of these changes. For now, the letter of the law is clear, but the path from statute to practice is still highly uncertain.

-

Footnotes

- Parent and certain graduate borrowers must pass an ‘adverse credit’ check that they have no recent defaults or other adverse credit events on loans over a de minimus amount.

- See table 3, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2024-06/51310-2024-06-studentloan.pdf

- There are several other fixed plans, like graduated and extended repayment, that allow borrowers to repay their loans over a longer timeframe than the 10-year standard plan.

- The available data do not allow for an estimate of the share of students who would be affected by the annual and cumulative limits jointly.

- One reason that graduate students in certain health professions are especially impacted is that the current annual Graduate Unsubsidized limits for students in those programs are higher than for students in other programs, and higher than the new Unsubsidized limits. Even for students who did not borrow Grad PLUS loans, then, they might have had an annual loan amount in excess of the new graduate loan limit for non-professional programs. For more, see: https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/dear-colleague-letters/1999-07-01/gen-99-21-extending-institutional-eligibility-award-increased-loan-amounts-health-professions-schools.

- The terms are defined by loan balances as follows: under $25k = 10 years; $25k–49,999 = 15 years; $50k–99,999 = 20 years; $100k+ = 25 years.

- Workforce Pell programs must be at least 8, but fewer than 15, weeks in length, and at least 150, but fewer than 600, clock hours. Programs that are at least 15 weeks and 600 clock hours in length already qualify for Pell Grants.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How OBBBA reshapes student lending

January 28, 2026