Appendix 1 was modified on January 16, 2026, to reflect the most accurate information on rehirings. Special thanks to Nikola Misetic for his research work on this paper.

It has been 10 months since Donald Trump was inaugurated as president for his second term. In this period, the federal government has experienced an unprecedented number of cuts to the workforce. These reductions have come rapidly, often in defiance of existing laws, regulations, and norms, leading to a significant number of lawsuits.

While the cuts are still being litigated, another more immediate question has arisen: Can the government continue to operate with a greatly reduced workforce, or will it fail to deliver essential services in ways that negatively affect ordinary Americans?

Polling shows that significant numbers of Americans are worried that the cuts have gone too far. For instance, a Washington Post poll found that 63% of Americans disapprove of Trump’s “handling of the federal government.” Fifty-seven percent of Americans feel that the Trump administration’s workforce changes will have a negative impact on the country.

To get a sense of where the government’s downsizing efforts stand in the fall of 2025, we have compiled available data and created a snapshot of the current situation. The overall picture looks like this:

- In many instances, agencies have had to rehire workers they fired.

- The uncertainty associated with downsizing has incentivized a large number of workers to leave the government through the deferred resignation program, buyouts, early retirements, and retirements.

- In some places where workers are needed to meet President Trump’s policy goals, deliver necessary services, or keep air traffic flowing, the government is not only rehiring people but also bringing new people on board.

- Government agencies are still listing thousands of jobs on the government website USAJOBS, although only a fraction of the total advertised are leading to hiring decisions.

The fact that ordinary Americans have come to question the downsizing is, most likely, the result of its rapid unfolding, with large cuts done quickly regardless of their impact on the government’s functioning. One outcome of this implementation is that agencies across the government have had to reverse course, rehiring employees they dismissed or rescinding offers of deferred resignation.

One of the earliest and most dramatic examples of the government rushing to rehire workers came from the Department of Energy. It may come as a surprise to many Americans that the Department of Energy is also responsible for managing the nation’s nuclear weapons program. As of 2023, America’s nuclear arsenal consisted of 3,748 warheads, some active and some inactive. This number is dramatically down from the height of the Cold War.

Within the Department of Energy, the National Nuclear Safety Administration employs about 1,800 federal government workers who oversee a contracting workforce of over 55,000. Their job is to make sure that America’s nuclear arsenal is safe and ready, which is why they employ hundreds of scientists and engineers. These employees are highly trained and possess skills that are in high demand in the private sector. Thus, retention is a problem, and staffing levels were deemed too low even before the second Trump administration took office.

On February 13, 2025, as part of a large package of firings at DOE, 350 people from the NNSA were fired. The blowback was immediate. “The DOGE people are coming in with absolutely no knowledge of what these departments are responsible for,” said Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association. The DOGE team saw the problem immediately; after all, no one wants to be responsible for the mismanagement of nuclear weapons. Within 24 hours, the firings were reversed, and the agency scrambled to reinstate everyone.

This was the first of many similar instances. As of this writing, we have recorded 25,747 occasions where the Trump administration abruptly fired people and then hired them back. As you can see in Appendix #1, this number is based on news reports and press releases from trusted sources that cover federal agencies. Unfortunately, at this time of tremendous change, there is no official government tracker of the number of people who have been rehired.

The reversals are connected to a wide range of functions of the federal government. A quick review of the reversals makes clear that the negative stereotype of the “paper-pushing bureaucrat” is largely inaccurate. Those being rehired include engineers, doctors, and other professionals whose work is critical to national security and public health.

Here are some examples.

At the Department of Agriculture, 58 facilities tasked with responding to avian flu were notified that 25% of their staff would be laid off. The firings drew immediate criticism from a number of Republicans in Congress. Avian flu was a significant driver of the rise in the price of eggs—an issue that then-candidate Trump repeatedly highlighted on the campaign trail. Any slowdown in avian flu response risked prolonging high egg prices and undercutting a political argument that Trump often invoked. The Department reversed the firings quickly.

Early in the Department of Health and Human Services’ transition, the Indian Health Service dismissed 950 health care workers, a decision that was swiftly reversed following strong objections from tribal leaders. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HHS reversed layoffs for over 722 employees, 400 of whom were from critical environmental health and infectious disease prevention centers. At the Food and Drug Administration, food examiners, who review the safety of food processing plants and other aspects of our food supply, were let go. But in May, it was reported that the agency planned to rehire for a variety of positions, including food and medical-device reviewers, communications staff, scientists, and even travel bookers. While travel bookers may sound peripheral to the mission of the agency, their role is important: in order to inspect plants, employees are constantly traveling around the United States, and that work depends on efficient travel logistics.

During the 2025 government shutdown, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) announced over 4,000 reductions in force (RIFs) across the government, despite the questionable legality of issuing RIFs during a shutdown—a position later upheld by the courts. However, even before the courts’ pronouncement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had rescinded RIFs for 700 people who had worked on response teams for diseases such as Ebola, claiming that the RIFs were made in error. The reversals prompted a Yale University epidemiologist to comment, “Did they really not know they were firing the people tracking Ebola? Did they not care enough to find out who they were firing and what they did before sending termination letters?”

At the Department of State, former USAID employees were invited to apply for 800 jobs needed to perform functions that were once housed at USAID but have now been shifted to the State Department. (My own prediction is that as these programs prove valuable to American diplomats, additional components of USAID may eventually be restored.)

At the Treasury Department, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced plans to bring back 400 revenue agents and 300 revenue officers who had accepted deferred resignation offers. The rehirings were spurred by the discovery of skill gaps in tax processing, IT, and customer service. The IRS cannot bring in the revenue required to operate the federal government without these professionals.

This represents only a sample of the rehires listed in Appendix #1. Based on the available information, around half of these rehires appear to have been mandated by the courts. In some cases, the courts cited operational issues for the rehire. In about one quarter of the cases, the agency announced rehirings without or before a court decision, a tacit admission that the blanket firings that took place during the DOGE era placed the federal government in danger of not being able to accomplish some of its most important missions. The Trump administration is no doubt aware of the fact that deep cuts leading to implementation failures could boomerang on the president and the Republican Party. As I wrote in Why Presidents Fail and How They Can Succeed Again, historically, major government failures fall squarely on the lap of the sitting president, damage their public standing, and rob them of political capital.

In other parts of the government, people have been reassigned to keep functions operational. Two examples are the Social Security Administration and the Department of Homeland Security.

At the Social Security Administration, some early personnel decisions had to be amended. In late February, DOGE went into SSA, announcing it would cut the workforce from 57,000 to 50,000 but that it would “prioritize customer service.” As part of those cuts, the Washington Post reported that SSA was considering ending or curtailing its phone services for claims processing and direct-deposit bank account transactions. Phone services account for about 40% of claims and help customers who have issues with internet access.

DOGE also announced intentions to close 47 field offices, a figure corroborated by an internal planning document from the General Services Administration (which has the actual authority to end leases). The outcry from members of Congress who feared that their constituents would be deprived of SSA services was intense; at the end of March, the Acting Commissioner denied the office closures, saying they were only getting rid of “underutilized office space.” As of this writing, it is unclear whether offices have in fact been closed; what is evident, however, is that SSA has retreated from the staffing and service reductions implied by the original plan. This ambiguity underscores the need for greater transparency about the decision-making within federal agencies.

In any event, by mid-March 2025, 2,477 employees at SSA had accepted the voluntary separation incentive payment, leaving the agency shorthanded.

Sensitive to the serious delays in customer service, the agency reassigned some workers to try and stop the damage. According to the Center for Policy and Budget Priorities, “the Trump Administration reassigned 2,000 of the remaining SSA employees to backfill vacancies in field offices, teleservice centers, or processing centers—or to help address the backlog in disability benefit applications.”

But the reassignments did not stem the crisis in customer service facing the Social Security Administration. From January to April, the average time citizens had to wait to get a call back regarding their social security or disability insurance claims rose to 180 minutes, prompting frustrated calls and “ordeals,” as reported by the Washington Post.

By July, more reassignments and some technology upgrades had lowered wait times, but problems persisted. For citizens fortunate enough to secure enrollment before the cuts began, the checks will be coming without interruption. But every year, the number of newly eligible applicants grows, as more and more baby boomers become old enough to apply for benefits. They are likely to face long wait times for both phone support and in-person appointments.

In other parts of the federal government, workers have been reshuffled to support the large-scale deportation efforts of the Trump administration. Making good on the pledge to deport millions of illegal aliens requires massive manpower, and it takes years to recruit and train border patrol and other agents. That’s why the administration turned to law enforcement employees assigned to agencies unrelated to immigration.

A Cato Institute study found that “ICE is receiving assistance from nearly 17,000 non-ERO [Enforcement and Removal Operations] agents, including 14,500 federal criminal law enforcement officers.” For instance, FBI agents have been moved to support immigration enforcement, meaning that other functions of the FBI, such as counter-terrorism, are being performed by fewer people. Other law enforcement officers have been transferred from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF), and the Federal Marshals. A complete list can be found in the Cato Study.

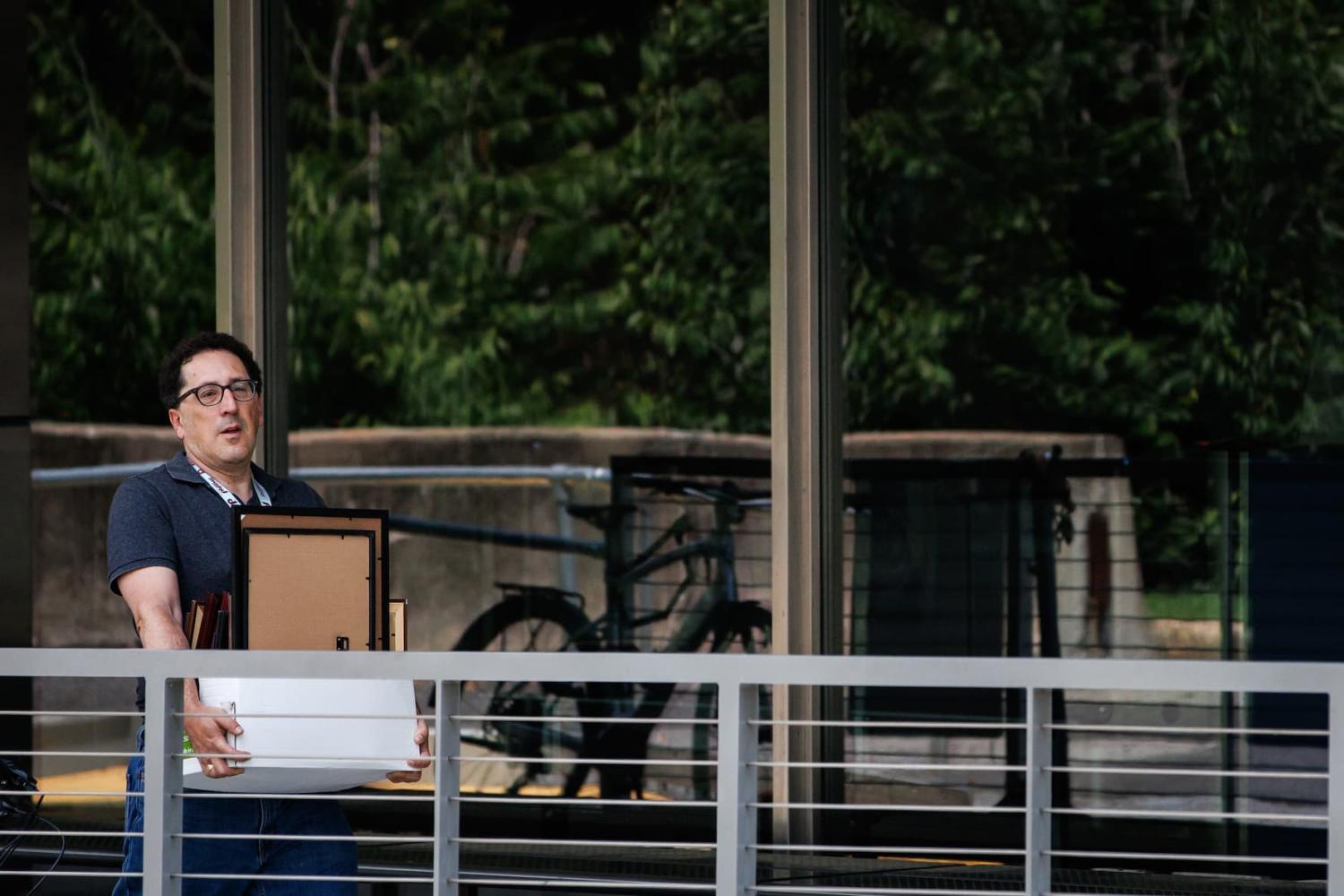

Emblematic of how many federal workers reacted to the chaos of firings and rehirings is this reporting from NPR: “Nobody knew anything. Management didn’t know anything. Nobody really knew if your job was safe,” says a former SSA employee. “I thought, better just to take it voluntarily than being forced out.”

DOGE’s attempts at large-scale firings had indeed the effect of inciting many workers to “voluntarily” leave the government. In the first 6 months of the second Trump administration, 154,000 federal employees signed up for the deferred resignation program. They were paid not to work for the remainder of the fiscal year; as of September 30, they have resigned, and most are no longer on the payroll. For reference, 115,900 workers left the federal government in all of 2023. The number is likely to be in that range in 2024 and could be exceeded in 2025, although it will be hard to differentiate normal turnover from deferred resignations.

Many of the people taking the deferred resignation offer are also retiring, creating a huge backlog in retirement processing. As a result, it is hard to distinguish the impact of deferred resignations from that of ordinary retirements in aggregate data. Nonetheless, in the first 6 months of 2025 (while the deferred resignation program was still available), more than 70,000 federal workers retired, a clear increase over that same period in 2024.

Compounding the problem, a hiring freeze has been in place since the beginning of the second Trump administration. Unlike in previous years, many workers who left for reasons unrelated to the administration’s push to downsize have not been replaced. Thus, in August, a spokesperson for the Office of Personnel Management estimated that 300,000 workers would leave by the end of the year.

In addition to rehiring fired employees and scaring others out of the government, some government agencies are actually hiring.

Airport delays and flight cancellations represent a highly visible issue with government service delivery. The recent government shutdown illustrated the importance of air traffic control. The economy cannot function without reliable air service, and hundreds of flight cancellations harm consumers and businesses. It is not a coincidence that one of the first cabinet secretaries to challenge Elon Musk during his time as the leader of DOGE was the Secretary of Transportation, Sean Duffy, whose agency includes the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Early on in Trump’s second term, the FAA cut probationary employees and then hired many of them back. Subsequently, Secretary Sean Duffy announced a plan to “supercharge” the air traffic control workforce by hiring an additional 2,000 people. According to Government Executive, “The initiative will include new retention incentives, pay bumps for employees who graduate from the controller academy, and an initiative to reduce the steps applicants must go through before beginning their careers.”

The Department of Homeland Security is also offering bonuses and other incentives to hire 10,000 new people into Immigration and Customs Enforcement and make good on Trump’s deportation promises. As reported by NPR, “As part of its recruitment campaign, DHS offered signing bonuses, lifted age restrictions and roped in celebrities like actor Dean Cain, who played Clark Kent/Superman in Lois and Clark, to encourage more people to apply.”

It may come as a surprise that, in spite of the downsizing efforts and a hiring freeze, the federal government is still advertising jobs.

USAJOBS is the U.S. government’s most prominent career website; not all jobs are posted there, and some agencies post on their own pages. That said, USAJOBS is a good place to get a sense of what is happening in the job market for government jobs.

As new roles are posted there, the status of the hiring process for each role is available. Using USAJOBS’ public API (Application Programming Interface), we created a list of every job that has been posted to the site since President Trump’s inauguration. We found that, as of mid-November 2025, of the over 73,000 posted jobs, a candidate was selected for only about 14,400 of them. While we do not know how many of those 14,400 workers actually had their first day on the job, the numbers illustrate the gap between the volume of jobs advertised and the progress towards filling them.

Furthermore, the 73,000 number tells us that despite downsizing efforts, many agencies feel they have an operational need for new employees. Agency-by-agency numbers of USAJOBS postings as of November 13, 2025, are listed in Appendix #2. More about our methodology can be found below.

The big question surrounding this entire issue is: Will the personnel cuts harm service delivery and confidence in government?

The patterns of rehiring in areas such as nuclear security and food safety indicate that the administration is aware of the potential for serious breakdowns that could jeopardize public safety and public health. Similarly, the effort to spare the FAA from downsizing suggests an awareness of the dangers posed by an understaffed air-traffic control operation.

As for those who “voluntarily” left because they feared getting fired or just couldn’t bear the uncertainty, it’s reasonable to infer that many of them were highly skilled and felt confident in their career prospects outside the government. At the same time, most of the new hiring appears to be in agencies that align with the president’s highest priorities, such as immigration enforcement. Non-priority agencies are still posting jobs, but it doesn’t seem that many positions are being filled.

In order to prove that the downsizing was worth the pain, the Trump administration will have to show that the government is still operating effectively. But much could go wrong. Nuclear mismanagement or airline accidents would be catastrophic. Late disaster warnings from agencies monitoring weather patterns, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and inadequate responses from bodies such as the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), could put people in danger. Inadequate staffing at the FBI could result in counter-terrorism failures. Reductions in vaccine uptake could lead to the resurgence of diseases such as polio and measles. Inadequate funding and staffing for research could cause scientists to move their talents abroad. Social Security databases could be compromised, throwing millions into chaos as they seek to prove their earnings records, and persistent customer service problems will reverberate through the senior and disability communities.

We may not have an accurate count of the Trump administration’s downsizing efforts until January 2029, when a new president takes office. It is possible that actual numbers will be less worrisome and that agencies will replace manpower with better technology, enabling more efficient service delivery. It is also possible that the federal government won’t have changed in size very much at all, or that a new crisis, such as a war or a pandemic, will result in a larger federal workforce.

But in the meantime, President Trump has to worry about potential meltdowns in government performance related to the rapid and aggressive downsizing his administration has pursued. As Harry Truman famously said in reference to the office of the president, “The buck stops here.” One of Trump’s ultimate legacies will be whether a downsized government leads to catastrophic breakdowns or increased efficiency.

-

Methodology

The data for Appendix 2 is sourced directly from USAJobs. Most federal job data that exists on USAJobs is publicly consumable and accessible through an Application Programming Interface (API).

For our purposes, we extracted data from their “HistoricJOA” API, which delivers data from all current and past job postings filtered by a set of standard parameters. Our researchers created code in Python that extracts the data directly from the source and converts it into a .csv file. Following this conversion, we cleaned up the data to ensure we successfully filtered out duplicate announcements and “test” postings (i.e., announcements that are titled “TESTING” or “DO NOT APPLY”).

After completing the cleaning, we can see the department and agency attached to any particular job posting. Most importantly, the “HistoricJOA” data gives us the status of each job after it is taken off the site. Through this, we can clearly identify canceled jobs, jobs that have decided on a candidate, and jobs that are still open.

In the interest of transparency, it is important to note that updates to the “HistoricJOA” API are the responsibility of each agency and are not live. As shown in the appendix, the information presented here was last pulled on November 13, 2025. Regardless, the data gives us a great overall look into the administration’s hiring trends and the government’s perceived need for personnel.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).