This is the fourth piece in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills, including problem solving, metacognition, critical thinking, and collaboration, in classrooms.

Australia’s response to the need to develop students’ 21st century skills is found in the Australian Curriculum’s general capabilities (including literacy, numeracy, information and communication technology (ICT) capability, critical and creative thinking, personal and social capability, among others). In order to embed these skills in Australian classrooms, guidance to teachers consists of online resources and the general precept that the capabilities should be developed where the key learning areas provide opportunities to do so. This approach is strongly aligned with the views of experts on systemic curriculum implementation, and with focus on learning opportunities rather than delivered curriculum.

One of us, Loren Clarke, a curriculum leader at Eltham High School, a large public secondary school in Australia, focuses on developing curriculum initiatives that support this approach. The school has undergone a process of curriculum renewal over the past 8 years in order to better support the critical thinking and collaborative skills of students, beginning in the first year of secondary education. Drawing on content from English, Science, and Humanities, the teachers taught “Integrated Studies” to help to focus student attention on 21st century skills, particularly collaboration, problem solving, and critical thinking. Taking an “active learning” approach, students are encouraged to interrogate information and focus on understanding problems that affect the community.

Debating the use of nuclear energy or legalizing euthanasia, for example, requires students to understand multiple sides of a debate by collecting a range of information and analyzing the positions of different stakeholders. The students then work as a group to develop a position that can be used to convince others. The inter-disciplinary Integrated Studies subject is aligned with the school’s overall teaching model: it is inquiry-based and places collaborative and critical thinking at its core. Students are guided through the “doors” of the research process.

Students are challenged to design research. For example, they might consider how their education compares to someone a decade ago and work with others to explore this. In order to build critical thinking skills as they design their research, they are assigned scaffolding tasks, which prompt them to think of similarities and differences—across persons, environments, technologies, and the resources from which they draw. These scaffolding tasks strengthen the students’ critical thinking by guiding them through systematic steps as they proceed from premise to conclusion.

“The critical thinking process prevents our minds from jumping directly to conclusions. Instead, it guides the mind through logical steps that tend to widen the range of perspectives, accept findings, put aside personal biases, and consider reasonable possibilities.” – 6 Steps for Effective Critical Thinking

We teach the language of critical thinking so that students understand the structure of an issue, comprised of elements including argument, premise, evidence, and contention.

Understanding the basics of critical thinking is essential for students embarking on the process: What is an argument? When you state an argument, you need to offer reasons for it, and these reasons, as well as parts of reasons, are known as premises. Have a look at the Rabbit Rule!

Students then engage explicitly in a “thinking stage” which focuses on the synthesis of learning and application of critical thinking skills. In the classroom, we may give students a fishbone diagram to identify their key ideas and connect these to their central research proposition.

These approaches allow students to develop explicit strategies for dealing with information. Working collaboratively, they discuss their increased awareness of how they are positioned by information, the way arguments are constructed, and how to use this information to construct their own position.

As an anecdotal snippet, an external presenter recently came to speak to the students about cyber safety, the need to stay safe online, and the various reasons. At the conclusion of the presentation, two Year 7 students approached the speaker and made the following comments:

“Your premise that we are more likely to encounter cyberbullying is flawed because you have ignored evidence regarding…”

“But your argument that we need to take responsibility ourselves seems to indicate your bias toward…”

Critical thinking can become embedded in student thinking—this is just one indication that the school’s approach is having some observable impact on student thinking and learning.

A BIG question

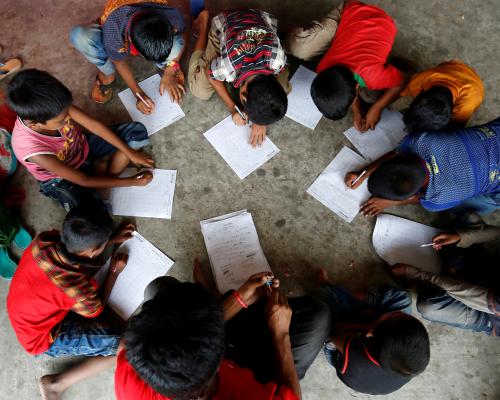

One of the BIG questions is how to introduce approaches such as this in traditional classrooms where the norm might be not to question, or where questioning might be seen as disrespectful of the teacher. Classrooms have their own cultures and implementation of the strategies outlined here may not be straightforward. Beyond just the individual classroom culture, and moving toward national or regional cultures, Hofstede (1986) proposed four factors that act across cultures. These all have consequences for the sort of critical thinking approach outlined above but we highlight just one.

Power Distance is a concept that refers to perceptions of equality-inequality and power. With large power distance, less powerful people are considered less equal, and there are corresponding notions of what behaviors are appropriate for those at different levels of power. Questioning someone in authority might not be socially possible, even within the context of a learning environment. With small power distance, there is greater presumption of equality, again with consequences for what behaviors might be acceptable. Societal or classroom concepts of power distance have practical consequences for the degree to which critical thinking approaches can be nurtured, and tolerated, within classrooms. Teachers’ confidence in their role is an essential ingredient in encouraging and supporting critical thinking in the classroom. Both teachers and students need to recognize the difference between respect for the person, and a critical and curious approach to concepts and ideas.

Reference

Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10, 301-320.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How do you teach critical thinking when the norm is not to question?

December 5, 2017