Placemaking Postcards is a blog series from Transformative Placemaking at Brookings where policymakers and practitioners guest-author promising placemaking efforts from across the U.S. and abroad that foster connected, vibrant, and inclusive communities. In line with the principle tenets of placemaking, the goal of the series is to recognize the community as the expert, highlight voices from the field, and to create a community of learning and practice around transformative placemaking.

No individual or organization can be credited for the work alone, as this is a collective product driven by the community. The lessons detailed in the piece are derived from various perspectives and shared wisdom.

The most expensive public works project in the history of Hawaiʻi is making its way across the island of Oʻahu. Once fully opened, the Honolulu Rail Transit Project will consist of 18.9 miles of track and 19 stations, with trains averaging 30 miles per hour at $3 per ride. Today, however, track construction crawls at roughly 1 mile per year at $600 million per mile, while the people most impacted remain largely disconnected from government decisionmaking.

Now that rail construction has reached Honolulu’s urban core, a river of heavy machinery and traffic cones cuts through the makai (ocean) side of one of the city’s most vibrant, culturally diverse, and working-class communities: Kalihi. Rooted in Native Hawaiian moʻolelo (stories), Kalihi embodies the soul of Hawaiʻi—an inviting space for longtime residents as well as immigrants across generations.

From the lens of outside prejudice, however, Kalihi can look different: a place of deficits, with poor health outcomes, youth gangs, dilapidated housing, and homelessness. It is the home of Hawaiʻi’s largest jail, public housing units, illegal game rooms, and one of Honolulu’s highest poverty rates. This perpetuates the false idea that something is “wrong” with Kalihi, making it a prime target for redevelopment.

This piece is about how governments and developers can learn from the local knowledge of people in places like Kalihi to rewrite both the language and process of development to truly center community benefit.

From ‘community engagement’ to community power

Kalihi is home to a number of ambitious development efforts. The city’s transit-oriented development (TOD) plan envisions 6,000 additional housing units with retail and commercial spaces around three rail stations and thousands of new jobs, while plans for public housing redevelopment projects in the area promise thousands of more housing units. Together, these represent one of Hawaiʻi’s largest coordinated redevelopment efforts.

Each development effort claims to be informed by community engagement. The TOD plan states that “neighborhood board meetings, public workshops, interviews, a survey…and a project website providing opportunities for input” were integral. Despite this commitment, there are clear signs that this engagement was inadequate in reaching impacted residents. Community meetings were scheduled at hours when working people could not attend; barriers related to language, culture, and distrust in developers remained unaddressed; and survey input from residents was clearly ignored in the final decisionmaking. Today, even well-informed community members are only minimally aware of current plans due to confusing messaging and limited developer engagement.

It appeared to many Kalihi residents that “community engagement” was just a performative exercise that accompanied efforts to maximize financial and political self-interest. Some firmly believe that the redevelopment’s true intention is to replace low-income people with high-income people.

But if gentrification isn’t the goal—which developers and city stakeholders claim—then residents felt that something else must be wrong with “community engagement” in its current form, in which the process often ultimately results in greater levels of misunderstanding and mistrust. This tension was clearly expressed by a Kalihi resident and community leader, who described her experience at a TOD planning meeting as both hopeful and alarming. She was encouraged by the developers’ invitation to hear the voices of the community, yet left fearful that they couldn’t see beyond their own visions of development based on preconceived ideas that were out of step with the community’s values and priorities:

I am in a place of hope and fear. Hope because you invited us to this summit and you gave us a space to listen, learn, and share our voice. Fear of losing who we are as people of Kalihi in the name of ‘development’ as envisioned by others.

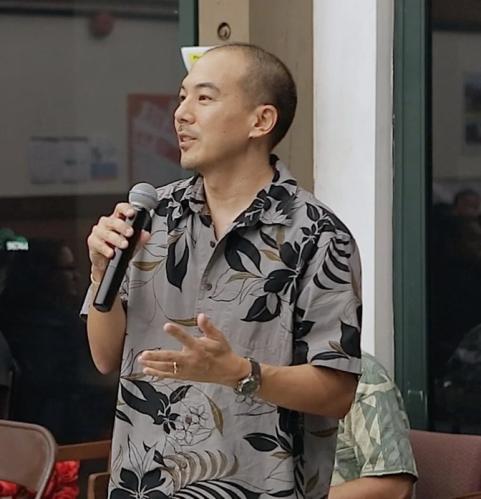

Recognizing the importance of genuine community engagement, our organizations—Kōkua Kalihi Valley (KKV), an innovative community health center based in Kalihi; Islander Institute; and Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) Hawaiʻi—began partnering in 2023 on an in-depth effort to understand residents’ views on economic development. As part of this, we embraced the framework of community-centered economic inclusion, co-developed by LISC and Brookings, to value both the process and outcomes needed to build community power during large-scale development projects.

‘Economic inclusion’ requires redefining language

KKV and Islander Institute designed intentional “talk-stories” (Hawaiʻi’s informal institution of being connected in conversation) with Kalihi residents across a range of backgrounds. The process—which took place from November 2023 through November 2024—relied on meeting people where they were comfortable, called together by people they trusted, nourished with good food, and conducted with the language and laughter that made them feel safe and free.

We asked people what they desired from economic development through basic questions such as: What does “wealth” mean to you? How does someone get that wealth? What do you love about Kalihi? What do you wish was different? Our conversations with community members (documented fully in our report, “The Economic Values of Kalihi”) revealed that redevelopment plans often used terms in ways that were fundamentally disconnected from community values.

For instance, when one developer presented the idea of “healing wellness,” they said it could look like the Planet Fitness at the Ala Moana mall. One Kalihi resident expressed dismay at this symbol of health, explaining that to them, true well-being wasn’t found in a gym, but in spending time with family and being in a kindred relationship with the ʻāina (land):

What I know from my work with Kalihi people is this: Health is spending time with families at the beach, fishing together, planting fresh vegetables. Health is working on bikes and playing basketball with friends at the park.

This also applied to concepts like safety. Ask outsiders to describe Kalihi and the first word that might come to mind is “unsafe.” They might point to crime statistics, gang activity, and gun violence, which are real issues. Yet in conversations with residents, by far the most common response to the question “What do you love about Kalihi?” was that it is safe. Residents shared that they feel safe because they know their neighbors, share common struggles, and maintain cultural practices that create belonging. This sense of safety emerges from a social fabric woven across generations.

Throughout this process, we learned from Kalihi residents that when developers use language like “health,” “safety,” “culture,” or “parks,” they can fail to grasp what Kalihi already has. In Kalihi, the park is the gym for those who can’t afford a gym membership; the public barbecue pit is the party hall and conference center for those who can’t afford a room rental and caterer. Parks hold the potential for people to grow, eat, and share healthy food for themselves and their community. Parks are where health and safety are generated, culture is perpetuated, and community spirit is nurtured.

Centering community values in development process and outcomes

Kalihi residents pointed to a fundamental challenge: Generic language within plans can portray development outcomes as incontrovertible—with the idea that “enhancing,” “reimagining,” and “revitalizing” can miraculously change the “bad” while preserving the “good”—while promising results such as housing, jobs, commercial activity, and more.

Take the goal of increasing jobs. Eighty percent of Kalihi jobs are filled by people living outside of Kalihi, while many residents struggle to meet basic survival budgets. Redevelopment promises jobs, but residents want to know: For whom? And what kinds of jobs will they be? Kalihi residents want jobs they are proud of, that contribute positively to the community, that provide living wages and security, and that allow time for family, culture, and relationships that create community health.

On housing, everyone agreed that Kalihi badly needs more, but residents were unclear if new housing will match their financial conditions, tastes, or cultural needs. For some of Kalihi’s families, multigenerational living is a cultural preference as much or more than it is a financial necessity. Yet development plans show little indication of this view being heard and respected. One resident said that developers were trying to erase the parts of Kalihi that made it home instead of honoring them, and that residents wanted to heal Kalihi, not completely alter it: “Kalihi doesn’t need to be changed. It needs to become well.”

Organizing community: Insisting on a seat at the table

Moving forward, the partnership between the community, KKV, Islander Institute, LISC Hawaii, and others will build on the community insights embedded in “The Economic Values of Kalihi” to bridge the gap between redevelopment efforts and community wishes.

As a core anchor of the effort, KKV embodies the principle of ʻāina (land) as the true healer and offers land-based cultural activities, a food hub and restaurant that sources from local farmers, youth programs teaching leadership through bike repair, Native Hawaiian-based birthing programs, and programs for kūpuna (seniors) in addition to traditional medical services. Their work is guided by the framework of Pilinahā, which states that good health is indicated by four connections: to place, community, past and future, and one’s better self. By these holistic measures, Kalihi is much healthier and wealthier than outsiders might expect.

Throughout this process, deep community engagement efforts revealed that the common words of redevelopment—such as parks, good jobs, health and wellness, and housing—can have significantly different meanings when used by Kalihi residents versus by developers and policymakers, with the potential for significantly different outcomes. Whether residents are fearful or hopeful depends on whether policy decisions ensure that their voices are not just heard, but heeded.

Reflecting on lessons learned throughout this process, our experience reveals several important action items for future development efforts, including:

- Listen to—and actually heed—resident recommendations. A combination of constructive engagement and action will help ensure that residents are not merely treated as consultants when determining the future of their community. Residents of the public housing complex known as Kūhiō Park Terrace, for instance, have been organizing against poorly executed redevelopment through rallies, hearings, lawsuits, and demonstrations. They want others to know that living in dilapidated housing hasn’t stopped them from forming a community and wanting a stake in its future. Public housing redevelopment is the opening salvo for what is coming to Kalihi once the TOD plan is in full swing, and by remaining organized, Kalihi residents are shaping their own future.

- Trust community-based anchors to catalyze trust-based development. KKV is among many Kalihi nonprofits seeing the big picture of redevelopment. These organizations play a key role in catalyzing community action, making space for residents to come together, and providing skills and training. Together, they are partnering to build community-based expertise in areas such as economic development, regulatory processes, and zoning laws, while cultivating relationships with potential allies in philanthropy, business, government, and academia.

- Invest in innovative, community-led models. While confronting external development pressures, Kalihi will also explore community wealth-building through community land trusts, resident-owned housing, and locally controlled development corporations. Food sovereignty projects, for instance, can restore relationships to the land while providing healthy, affordable nutrition. Cultural education maintains language and traditions while building youth leadership. And cooperative businesses create good jobs while keeping profits in the community.

Across decades, redevelopment planning on Oʻahu has been arduous and uneven. Today offers more reason for hope. “The Economic Values of Kalihi” report has been met with genuine curiosity and support. And Honolulu’s mayor has shown a keen interest in the innovative, good-government approaches exemplified in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge. This includes a desire to be honest and transparent with the public about intentions and open about solutions. In the words of one local city stakeholder:

The city is committed to doing TOD the right way. There is still a lot of time for meeting the people of Kalihi where they are, when they’re available, in ways they’re comfortable.

Kalihi residents have demonstrated that an abundance of distinct cultural identities can coexist, that working-class values can create opportunity, and that people can care for each other and the land across generations. Whether these gifts survive—and spread to other communities facing similar development pressures—depends on our collective commitment to development that truly serves community well-being.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This work was made possible by support from the Kaiser Permanente Donor-Advised Fund at East Bay Community Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Kaiser Permanente Fund at East Bay Community Foundation, their officers, or employees.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How a Hawai’i community is moving from ‘engagement’ to ‘power’ in the redevelopment process

November 24, 2025