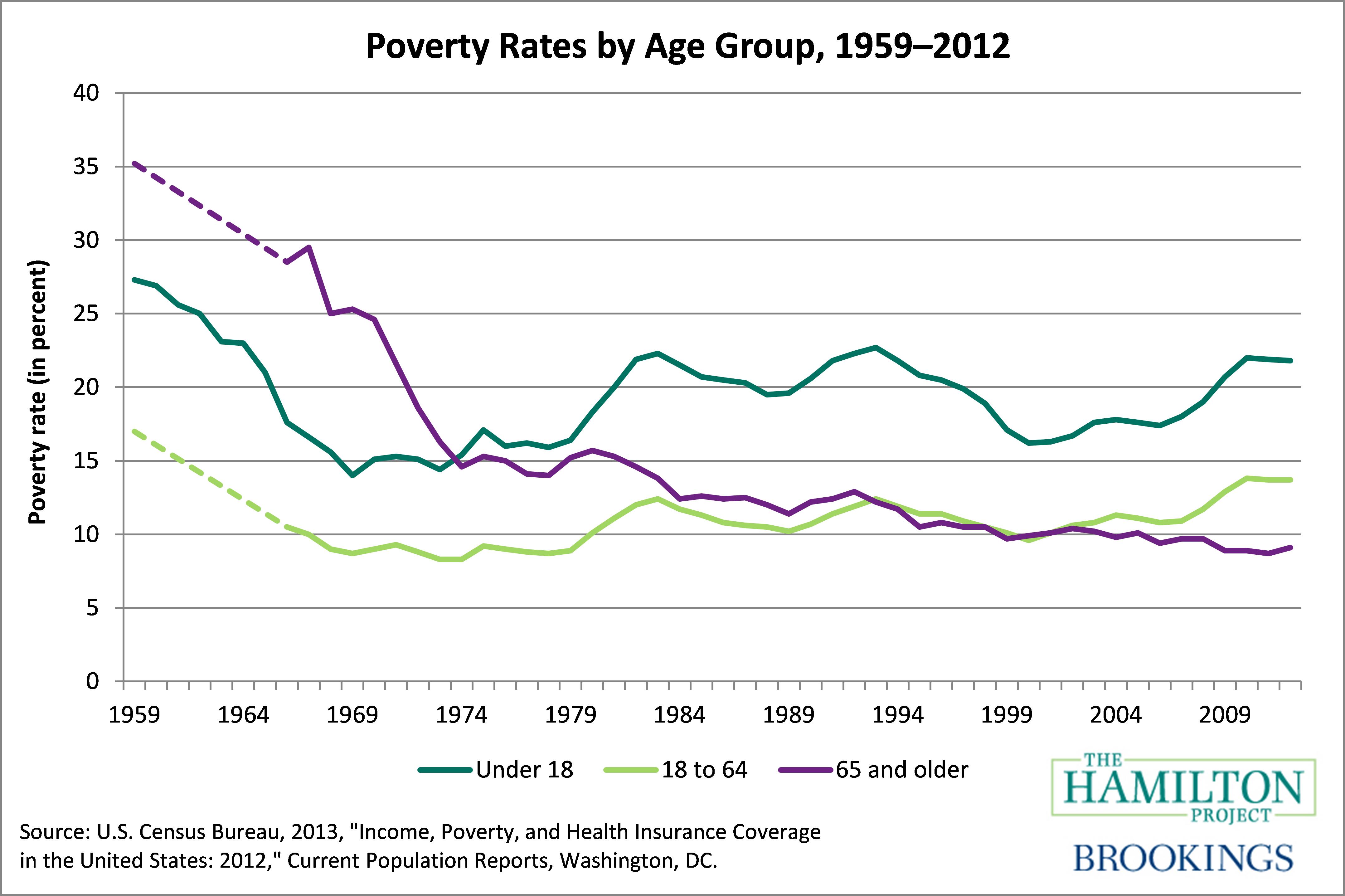

In 2012, 15 percent of Americans—30.4 million adults and 16.1 million children—lived in poverty, according to the official Census poverty count. Figure 1 shows how these rates have trended in recent decades, and underscores that rates are highest among children. Yet even these counts, as high as they are, understate our nation’s experience with poverty. For every person classified as poor, many more hover just above the poverty threshold, weaving in and out of poverty depending on their circumstance.

Figure 1

Indeed, a surprising 29.6 percent of families currently live within 150 percent of the poverty level; for a single individual, that means an annual income of less than $18,179, and for a family of four that means an annual income of less than $35,436.

For a country as wealthy as the United States, this seems unfathomable. And the reality of living in poverty in America is harsh. It means not only material deprivation, but also the diminished life prospects that come with being poor. For millions of children in the United States, poverty means growing up without the advantages of a stable home, high-quality schools, or consistent nutrition. Adults living in and near poverty are often hampered by inadequate skills and education, leading to limited wages and job opportunities. And the high costs of housing, health care, and other necessities often mean that people must choose between basic needs, sometimes forgoing essentials like meals or medicine.

Poverty threatens not only those who live with its relentless hardships, but it also poses a real threat to our nation’s stability, social fabric, and economic future. Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to drop out of high school, are more likely to engage in risky behaviors that can lead to juvenile detention and ultimately incarceration, and are more likely to become young unmarried parents. If those at the bottom of the income distribution are left behind, finding middle-class life increasingly out of reach, then the United States risks a perpetuation of poverty and inequality, and a permanent class of people who do not productively contribute to or benefit from our nation’s economic riches.

Though poverty rates remain high, much progress has been made since the War on Poverty was declared fifty years ago. These efforts have led to a strong safety net that is absolutely necessary to support the least skilled and most economically disadvantaged among us. Credible estimates reveal that without our nation’s crucial safety net programs, the rate of poverty in America would be twice as high.

Having a strong safety net must be part of our nation’s fight against poverty. And these programs should neither be viewed as nor designed as “band-aid” solutions—they should be designed and supported as investments in the long-term health and well-being of individuals. Without sufficient income to guarantee a safe home environment or adequate nutrition, children cannot thrive in school and build the health and human capital they will need as adults to compete in a globally competitive economy. Without temporary support, non-working or low-wage individuals are not able to return to school or engage in training in order to improve their economic position. We have evidence on and experience with how to design income-support programs in ways that encourage work and benefit individuals and families. We must build on that success.

Along with expanded and well-designed social programs, technological advances have also brought important progress to the fight against poverty in this country. For example, modern conveniences such as television, air conditioning, and even cell phones are now enjoyed by almost all Americans. But along with these improvements have come new challenges. Global labor market forces—driven at least in part by technological factors—have made it increasingly difficult for low- and middle-skilled individuals to find and keep well-paying jobs.

Skill development must be a critical component of America’s anti-poverty strategy. It is increasingly difficult for individuals to be economically secure in today’s global economy with limited skills and education. We must recognize the paramount role of skill upgrading in fighting poverty in this country. This will require not only significant improvements in our K–12 education system, but also a commitment to increased enrollment, persistence, and (crucially) completion of higher-education programs. In addition, policies are needed to ensure that our educational programs—both in high school and at the college level—prepare students for the labor market.

In addition to modern labor market challenges, changes in family structure and childhood environment have heightened disadvantage for our nation’s poor children. The increase in non-marital childbearing among the less educated has led to large divergences in family structure and in childhood experiences between children from poor and rich households in ways that severely disadvantage children at the bottom of the income distribution.

Children from high- and low-income families are born with similar abilities, but different opportunities. And the outcomes of their economic circumstances become rapidly apparent. Despite similar starting points, by age four, children from wealthy families score higher on tests of literacy and mathematics than do their lower-income counterparts. There is an income gap in school readiness that persists into higher years of schooling. In fact, the difference in measures of school achievement between high- and low-income students has increased over time. For example, the average difference in reading standardized test scores between children from the 90th (the richest) and the 10th (the poorest) income percentile of families has increased by almost 40 percent since 1970. This is not an instance of the poor doing worse, but a case in which students from wealthier families are pulling away from their lower-income peers due to higher levels of parental investments in their children’s success.

The rate at which disadvantaged youth drop out of high school is another concrete measure of how our nation’s poor youth struggle to move up the economic ladder. According to recent estimates, nearly four in ten eighth-grade students from families in the lowest income quartile fail to graduate from high school. The consequences of low educational attainment and a lack of labor market skills are too severe to ignore. Finding effective ways to foster the academic skills and socio-emotional development of disadvantaged youth through their teenage years must be a priority in our nation’s multipronged attack on poverty.

The American Dream is premised on the notion that social mobility is not only possible, but expected——where one generation can do better than the last. If today’s youth start off on an uneven playing field, never able to catch up with their higher-income counterparts, we risk creating a culture of poverty that threatens the foundation on which our country was built.

What should we do to address poverty?

Poverty is a complex, multifaceted problem that can be addressed only through a comprehensive set of innovative policies and effective reforms. Tackling poverty requires a national commitment toward building human capital, harnessing the economic power of that investment, and providing a safety net when jobs are scarce or individuals are intellectually or physically capable of economic self-sufficiency. It means a commitment to addressing the causes and consequences of poverty throughout the life course.

The Hamilton Project has commissioned 14 innovative, evidence-based antipoverty proposals. These proposals are authored by a diverse set of leading scholars, each tackling a specific aspect of the poverty crisis. The papers are organized into four broad categories: (1) promoting early childhood development, (2) supporting disadvantaged youth, (3) building skills, and (4) improving safety net and work support. The proposals are forward-looking and, if implemented, would have important beneficial impacts on the well-being of America’s next generation.

These proposals will be discussed next week as part of a two-day public forum in Washington, DC. The full proposals will be available on The Hamilton Project’s website (www.hamiltonproject.org) on Thursday, June 19th at 8:00 a.m. ET. To preview these topics, the introduction to The Hamilton Project’s antipoverty volume can be found here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fighting Poverty Needs to be a National Policy Priority

June 13, 2014