This article is part of the Brookings Center for Sustainable Development compendium “Innovations in public finance: A new fiscal paradigm for gender equality, climate adaptation, and care.” To learn more about the compendium’s chapters, cross-cutting themes, and policy-relevant insights, see the “Introduction: Six themes and key recommendations for embedding gender equality, care, and climate in fiscal policy.”

What defines and constrains fiscal space

Fiscal space most commonly refers to the ability of a government to expand spending for priority public policies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) defines it as “room in a government’s budget that allows it to provide resources for a desired purpose without jeopardizing the sustainability of its financial position or the stability of the economy”(paragraph 2).1 The core idea is that fiscal space is a limited resource, dependent on a government’s ability to raise domestic revenues and to borrow without jeopardizing future stability.

The IMF definition focuses on financial sustainability. Others place more emphasis on social, economic, and environmental sustainability, which in turn can influence the financial sustainability of the budget over the medium to long term.2 These feedback loops depend on the investment quality of public spending and the time frames over which returns accrue.

When government spending is utilized for profitable financial and economic investments, fiscal space can be expanded due to the surplus being created. Much of the literature on fiscal space, therefore, focuses on the multiplier effects of certain types of spending. For example, Seguino (2025) cites meta studies (e.g., Cardoso et al. 2023) documenting large multiplier effects on gross domestic product (GDP) and tax revenues of social protection in a range of country situations reflecting the high propensity to spend of poor households.3 She concludes that evidence supports the idea that multipliers associated with social protection expenditures tend to be larger than those from other types of government spending, that the size of such multipliers is especially large in countries that are poorer and more unequal, and that social protection pays for itself in the form of higher tax revenues, even after a decade.

The flip side of such arguments, however, is that if government expenditures do not create an economic surplus, then fiscal space contracts and expenditures cannot be sustained. The quality of budget allocation processes and implementation is therefore crucial. Viewed in this way, fiscal space is analogous to a depletable natural resource. Good investments can expand it, just as successful exploration expands a natural resource. And both should be treated and managed as an asset.

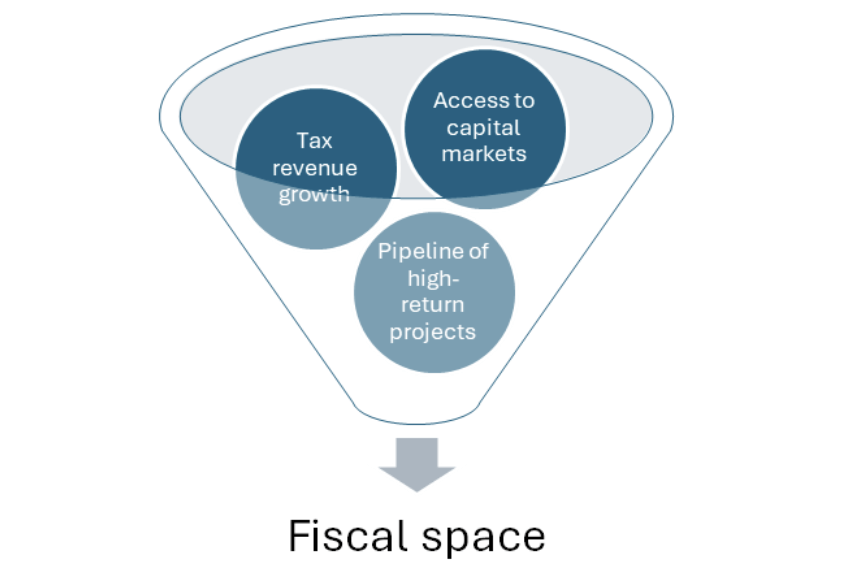

Over time, fiscal space is created by new revenue, in turn dependent on economic growth in an economy, and by the net returns on past investments. It is used up by expenditures that do not return equivalent net present value to the budget. Figure 1 depicts the three requirements for sustaining fiscal space:

- The speed of economic growth and the dynamism of the tax system in capturing some of those benefits for the treasury.

- The ability to identify and implement a pipeline of high-priority spending for which fiscal space is needed.

- An ability to access enough up-front financing to enable the priority spending to take place.

Figure 1. Three requirements for fiscal space

Measuring fiscal space

Fiscal space is sometimes measured simply as discretionary fiscal spending — the amount of revenue and borrowing capacity that is left over when non-discretionary spending has been subtracted out. Non-discretionary spending, in turn, is usually defined in terms of items that are deemed to be mandatory, either by economic or political necessity. Debt service and pensions are often core items of non-discretionary spending. In the United States, mandatory spending refers to entitlement programs, like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, that are available to everyone who qualifies, while discretionary spending has to be appropriated by Congress.4 Wages of civil servants are a grey area—in the United States, they are counted as part of discretionary spending, but in many developing countries, they are included in non-discretionary or inflexible spending, as firing of civil servants can be politically difficult and time-consuming.

The fact that fiscal space includes the option to borrow means that measuring fiscal space requires an estimation of the amount that a government is prepared to borrow, something that is derived either from a debt sustainability assessment made by an independent technical group, or in accordance with fiscal rules that have been passed by a country’s legislature. Both the modelling and rules-based approaches are typically designed to restrict the tendency of democratically elected governments with short time horizons to overborrow and overspend if not checked by an implicit social contract with citizens to pay their fair share in taxes.

Debt sustainability models

Debt sustainability assessments (DSA) are used by the IMF and World Bank to measure fiscal space in client countries.5 These assessments combine judgments on the soundness of macroeconomic and structural policies, crucial to understanding whether high-return spending is feasible, along with judgments on the ability to service external debt. The latter determines whether future fiscal space is being compromised or not by current actions.

The key economic variables in a fiscal space calculation are the size of the fiscal deficit, the rate of interest on government borrowing, and the growth of the economy and of exports. But even when these variables are the same across countries, the amount of fiscal space can differ due to differences in the quality of policies and institutions.

This last observation explains why debates over fiscal space can be so contentious. Most of the time, there is little major disagreement on the contours of economic policy. After all, current growth rates, deficits, and interest rates are observable, and while there may be uncertainty about the future values of these variables in the medium term, the real discussion about fiscal space hinges on judgments about the quality of institutions and hence of government borrowing capacity.

The IMF and World Bank have used historical episodes of debt distress to empirically estimate the maximum size of a sustainable fiscal deficit, given other exogenous economic variables like GDP, export growth rates, and institutional quality, proxied by the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment.6 From this modelling work, a maximum fiscal deficit is computed by imposing a requirement that debt and debt service levels remain below certain threshold values. The threshold values vary according to staff judgment on the quality of institutions and policies in each country. As a rough guide, developing countries with weak policies have threshold values that are half the value used for countries with strong policies.

The problem is that the modelling of debt distress episodes is inevitably imprecise. In a sample of 1356 country-year observations, the debt model used by the World Bank and the IMF forecast debt distress in the following year 523 times.7 However, only 40 cases (8% of the total) were correctly called. The remaining 483 cases were false positives, episodes when the model signaled imminent debt distress in the following year and hence called for radically reduced fiscal spending, but where the ex post outcome turned out to be benign. Conversely, the model showed a false negative in 19 of 833 cases (2%), wrongly suggesting that no additional fiscal action was needed in these cases to avoid debt distress.

For policymaking purposes, there is a tension in calibrating fiscal space models between the number of false positive and false negative signals that the model calls. The presumption is that false negatives should be minimized—that the cost of falling into debt distress is so large that all effort should be made to avoid such an outcome. This is why the thresholds selected in the DSA are chosen to be conservative. And indeed, when debt treatments require a net present value write-down, there is a long-drawn-out negotiation between creditor and debtor that results in substantial losses for both parties. But net present value reductions themselves are only a small fraction for emerging economies and low-income countries, about one-seventh and one-fourth, respectively, of debt treatments in the event of a default.8 In most cases, the needed action is a reprofiling of debt service obligations due, mostly to manage cases where a bunching of maturities has led to temporarily high debt service obligations or where a sudden fall in commodity prices has led to a temporary fall in foreign exchange receipts.

Fine-tuning a debt sustainability model to derive an estimate of fiscal space requires both understanding the risks of the model producing false positives and false negatives and understanding the consequences of taking action based on the model predictions. When there are too many false positives, fiscal space can be unduly constrained and high-priority spending may be deferred, at significant economic and social cost. Conversely, if there are false negatives, needed fiscal action may be postponed until it is too late, and a high-cost debt resolution negotiation becomes inevitable.

Fiscal rules

According to the IMF, as of the end of 2021, around 75 emerging market and developing economies have some type of fiscal rule.9 The most common rule relates to fiscal deficits, often called balanced budget rules. Such rules are typically combined with a debt rule that limits either the stock of debt, new borrowing, or debt service obligations. In addition, some countries have expenditure rules to limit the growth in spending, and others have revenue rules to encourage tax mobilization.

One issue with fiscal rules is that they can be suspended in responding to crises. Use of such escape clauses was extensive during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/9 and again during COVID-19.10 The spending associated with these crises used up considerable fiscal space, leaving open the question of whether to recapture space for future contingencies by temporarily running fiscal surpluses, or whether to amend thresholds and deficits to reflect the new reality.

Such questions are increasingly being addressed by fiscal councils, technical agencies with an official mandate to advise, interpret, and monitor government compliance with fiscal rules. Fiscal councils have been more widely used in advanced economies, especially in Europe, but a number of emerging markets have also introduced them, encouraging governments to comply with fiscal rules or explain any divergence.11 At their best, fiscal councils permit a reasoned discussion of the trade-offs involved in determining fiscal space based on a deep understanding of the social preferences of each country, rather than on generally applicable rules.

How to use fiscal space

Each dollar of spending does not necessarily translate into a dollar’s use of fiscal space. When spending is one-off, without direct returns to the fiscal accounts, there is an equivalence between spending levels and the use of fiscal space. Examples are livelihood subsidies enacted in response to COVID-19 or relief from a natural disaster, which may compensate for loss and damage but do not directly contribute to long-term economic growth.

Other kinds of spending may have a lower impact on fiscal space. For example, public spending on health and education, even if freely provided to beneficiaries, contributes to economic growth. Economic growth, in turn, adds to government revenues and so partially expands future fiscal space. The net effect depends on the rate of return of the spending, how much accrues directly to the government (if, for example, user fees are charged), and how much accrues indirectly to the government. In this last instance, the buoyancy of tax revenues is an important variable. The tax buoyancy gives an indication of the extent of fiscal revenue gains associated with GDP gains.

Most public spending on gender equality, particularly for care, falls under this category of spending that boosts economic growth but does not yield direct returns to the treasury. When the state or a community provides care or the physical infrastructure to reduce time spent on care, it enables women to undertake more work that is remunerated in a market economy, with additional benefits for gender equality and intrahousehold bargaining power.12 When women earn more, moreover, they spend on their children’s human capital, further adding to long-term growth benefits and a commensurate expansion of fiscal space in the long run.13

The impact of spending on fiscal space, then, depends on the multiplier between the spending and GDP, along with tax buoyancy. Both are country-, place and time-specific. For example, Cardoso et al. (2023) review multipliers from social protection spending in 42 developing countries and find positive and persistent effects that are larger in poorer and more unequal countries.14 Some studies have found multipliers to be sufficiently large that social protection pays for itself in the form of higher tax revenues, but there is significant variation in the empirical findings in this regard across all studies.15

It is easier to identify the impact of public spending on fiscal space when projects generate a direct, financial surplus. When governments invest in toll roads, ports, or clean energy generation, for example, they may generate a positive net revenue stream. If these investments are successful, fiscal space actually expands thanks to the investments.

Instruments to expand fiscal space

Macroeconomic and structural reform

A core variable in determining fiscal space is the quality of macroeconomic and sectoral policy and how this is interpreted by financial market actors. This manifests in a number of ways. Countries with better policies grow faster. They therefore add fiscal space more rapidly over time. When policies align with factors included in credit rating agency macromodels, governments are also able to borrow at lower interest rates and hence directly gain fiscal space by having lower levels of debt service. They can sustainably access capital markets, so they can afford higher levels of debt. Countries with strong tax buoyancy find that fiscal spending can yield considerable indirect revenues for the treasury that limits the extent of fiscal space being used by each dollar of spending.

Public financial management is a key ingredient in the broader concept of strong institutions and policies. Using the public expenditure and financial accountability (PEFA) toolkit, 607 assessments have been done at the country and sub-national levels of public financial management issues and trends between 2005 and 2021.16 The main issues: budget execution, transparency of fiscal reporting, and public investment management continue to be weak. Large subsidies for food and energy also eat up considerable fiscal space that could otherwise be used for higher priority spending. Countries can relax fiscal space constraints by shifting spending towards areas that create direct and indirect revenue streams for the treasury.

Concessional finance

External grants and concessional credits are significant sources of expanding fiscal space in low-income countries. They have permitted a scale-up of health and education spending, amongst other areas. But concessional flows are rarely fully reliable and predictable over time. For example, recent aid cuts have thrown health and nutrition programs in many countries into disarray. When concessional funds are used for non-tradable activities like health and education, they can also have an impact on real exchange rates that has to be considered.

Debt management and write-offs

Large volumes of debt owed by low-income countries were written off as part of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative and the Multilateral Debt Reduction Initiative. Both served to temporarily raise fiscal space. Over time, however, this fiscal space has been eroded, particularly due to the heavy fiscal expenditures associated with the pandemic response. The lesson is that debt write-offs only lead to a temporary expansion in fiscal space, not to a permanent expansion unless savings from the debt write-offs are profitably invested.

More recently, several large debt-for-nature swaps have been concluded, wherein debt service reductions are accompanied by spending increases in specified areas. Barbados (2024), the Bahamas (2024), Gabon (2023), Ecuador (2023), and Belize (2021) have each committed to expanding specific types of nature conservation—coral reefs, tropical forests, and mangroves—with savings derived from refinancing of existing debt at lower interest rates and reduced face values.17

Similar temporary relief is available from other forms of debt treatment. Debt reprofiling, such as through the debt service suspension initiative of the G20, offered countries an option to defer debt service on bilateral official debt in 2020 and 2021.18 This provided liquidity to governments, but unfortunately did little to halt the slide in public investment. Consequently, fiscal space has been lost as payments on the deferred debt are now starting. Meanwhile, the spending of the extra liquidity has not yielded significant new revenue.

In sum, the debate over fiscal space has clarified the different impact of types of fiscal spending on public finance in the long term. Entitlements and transfers to households can provide social protection but may be expensive in terms of fiscal space unless they have a direct impact on GDP growth, which can be the case in poorer countries and regions where aggregate demand is low. Fiscal spending that adds to growth uses much less fiscal space—how much depends on the social returns and on the ability of tax systems to capture a portion of the gains for the treasury. Certain types of public investment can actually create additional fiscal space for other expenditures if they generate more revenue than the net interest cost of the associated financing.

A sound understanding of fiscal space can help developing country governments prioritize the size and composition of their spending better. Such an understanding should pay greater attention to the long term impact of public spending on growth, as well as the short-term impact of such spending on economic stability and the avoidance of social unrest.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This policy note was prepared for the Brookings Compendium on “Innovations in public finance: A new fiscal paradigm for gender equality, climate adaptation, and care.” The author would like to thank Caren Grown, Laura Martinez, Stephanie Seguino and participants in a workshop/roundtable on May 8, 2025 for their comments. An earlier version of this policy note can be found here. The author would also like to thank Charlotte Rivard for her research assistance in preparing this note.

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or the funders acknowledged below.

This publication is supported by the Gates Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad). The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the donors.

Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

-

Footnotes

-

Heller, Peter. 2005. “Back to Basics — Fiscal Space: What It Is and How to Get It.” Finance and Development, June 2005.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2005/06/basics.htm -

Seguino, Stephanie. 2025. “Engendering Fiscal Space: The Role of Macro-Level Economic Policies.” New York: UN Women.

https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/engendering-fiscal-space-the-role-of-macro-level-economic-policies-en.pdf - Seguino, “Engendering Fiscal Space.”; Cardosa, Dante, Laura Carvalho, Gilberto Tadeu Lima, Luiza Nassif-Pires, Fernando Rugitsky, and Marina Sanches. 2023. “The Multiplier Effects of Government Expenditures on Social Protection: A Multi-Country Study.” Department of Economics – FEA/USP. Working Paper Series 2023-11. Made centro de pesquisa em macroeconomia das desigualdades. https://socialprotection-pfm.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/wp18_multiplier-multi-country.pdf

-

“The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2023 to 2033.” 2023. Congressional Budget Office. Nonpartisan Analysis for the U.S. Congress.

https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-02/58848-Outlook.pdf -

“Debt Sustainability Analysis — Low-Income Countries.” n.d. IMF. Accessed July 14, 2025.

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/DSA - “IMF-World Bank Debt Sustainability Framework for LIC.” 2025. IMF. April 2025. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2023/imf-world-bank-debt-sustainability-framework-for-low-income-countries

- “Debt Sustainability Analysis.” IMF.

- Ando, Sakai, Tamon Asonuma, Alexandre Balduino Sollaci, Giovanni Ganelli, Prachi Mishra, Nikhil Patel, Adrian Peralta Alva, and Andrea Presbitero. 2023. “Chapter 3: Coming down to Earth: How to Tackle Soaring Public Debt.” International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook. IMF. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2023/April/English/ch3.ashx

-

Davoodi, Hamid R., Paul Elger, Alexandra Fotiou, Daniel Garcia-Macia, Xuehui Han, Andresa Lagerborg, W. Raphael Lam, and Paulo Medas. 2022. “Fiscal Rules and Fiscal Councils: Recent Trends and Performance during the Pandemic.” IMF Working Paper No.22/11. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/Working%20Paper%20-%20Fiscal%20Rules%20and%20Fiscal%20Councils%20-%20Recent%20Trends%20and%20Performance%20during%20the%20Pandemic.pdf - Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Chiappori, Pierre-André, and Costas Meghir. 2014. “Intrahousehold Inequality.” Working Paper. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20191

- Himmelweit, S. 2016. “Childcare as an Investment in Infrastructure.” In Feminist Economics and Public Policy. J. Campell and M. Gillespie (Eds.). London: Routledge: 83-93.

- Cardosa et al., “The Multiplier Effects of Government.”

- Seguino, “Engendering Fiscal Space.”

-

“2022 PEFA Report on Global Financial Management.” 2022. PEFA.

https://www.pefa.org/global-report-2022/en/ -

Simeth, Nagihan. 2025. “Debt-for-nature swaps: A case study of Gabon.” Emerging Markets Review 65: 101244.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1566014124001390 - “Debt Service Suspension Initiative.” 2022. Text/HTML. World Bank, March 10. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/covid-19-debt-service-suspension-initiative

-

Heller, Peter. 2005. “Back to Basics — Fiscal Space: What It Is and How to Get It.” Finance and Development, June 2005.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2005/06/basics.htm

https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/engendering-fiscal-space-the-role-of-macro-level-economic-policies-en.pdf

https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-02/58848-Outlook.pdf

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/DSA

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/Working%20Paper%20-%20Fiscal%20Rules%20and%20Fiscal%20Councils%20-%20Recent%20Trends%20and%20Performance%20during%20the%20Pandemic.pdf

https://www.pefa.org/global-report-2022/en/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1566014124001390

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).