Forty years ago, Democrats and Republicans and business and labor joined forces to create the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). They did so because some companies that offered pensions ended up not paying them, leaving workers unprotected in their retirement years.

Because of ERISA, workers who still have traditional pensions are better protected. Before ERISA, some pensions didn’t vest, so people could lose their entire pension if they changed jobs or were laid off; some pensions weren’t funded; some pensions had no spousal protections or were reserved only for senior executives.

However, most workers do not have traditional pensions. The retirement landscape has vastly changed, but ERISA and the agencies that enforce it haven’t kept pace. Today, public policies often undermine retirement income security, rather than enhance it. This decline is not inevitable. The same creativity that created ERISA can enhance retirement security in the future—but the time to act is now.

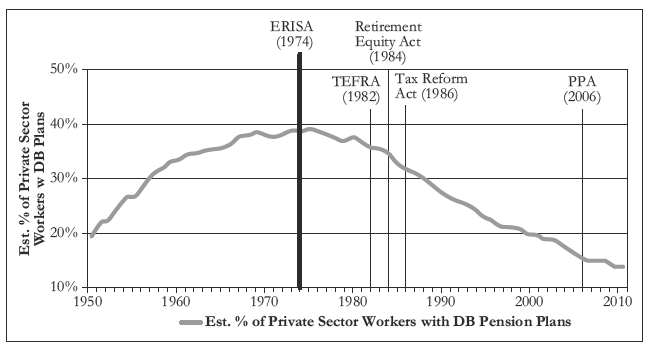

ERISA was defined benefit’s (DB’s) high-water mark. ERISA made traditional pensions more secure, but that security protects fewer and fewer workers. The law assumed that employers would voluntarily choose to offer lifetime income security to workers through traditional DB pensions. Increasingly, however, they do not. As the graph below shows, the percentage of private-sector workers with DB plans peaked in the 1970s, as employers increasingly chose defined contribution (DC) plans or individual retirement accounts (IRAs)—if they offered a plan at all. In 1979, about 40 percent of private sector workers had pensions that provided lifetime income; today, that number is less than 15 percent, and many plans pay benefits as lump sums.

In part because neither Congress nor the agencies that imple- mented ERISA kept pace with the times, retirement income security has eroded along with the DB plans ERISA was intended to protect. The combination of a shift to individual account plans and the his toric market drops of the past 10 years has taught millions that their retirement is insecure; some think they can never afford to retire at all.

The good news is that this problem, though large and complex, has solutions.

- There are still 75 million people with DB plans, so part of the answer is to preserve them.

- For the remainder, the challenge is to develop plans that offer lifetime income security on terms that employers and employees can afford. Here, too, others have made progress

and there’s no reason we cannot as well.

A Retirement Crisis?

Most people can’t figure out return on investment or read a mortality table, but they know there’s a real problem.

Thirty-five years ago, 25 percent of people surveyed were concerned about adequate retirement income; today that’s 61 percent and the percentage has been rising. Retirement insecurity is now the most broadly felt component of economic insecurity (more widespread than Americans’ previous top concern: healthcare costs).1

The ERISA community, by comparison, seems passive. Some quibble about whether this is a “crisis.” Others seem to be channeling Elisabeth Kübler-Ross:2 some are in denial; others accept that “pensions are dead.” (Of course, they don’t say so publicly. No one talks about death.)

Neither approach works very well. The “deniers” are pretending that the actions of the past haven’t resulted in a major degradation of retirement security; by continuing the mistakes of the past, they will ensure that pensions have no future. Those who think pensions are dead and that we should move on are missing the easiest way to preserve retirement security: preserve the plans we already have— plans that cover some 75 million people—and preserve some role for employers in providing them.

Why Employers Quit

Many factors affect the choice of benefits, but the primary ones are relatively well-established. The most important is the cost of a benefit, particularly compared to the value employees perceive in it. (Generally, employees find an account balance easier to understand and value more easily than an income stream.3) Unfortunately, Federal law deters sharing of DB retirement costs with employees by permitting tax-deferred employee contributions only to savings plans, not to DB pensions. In public retirement plans, by comparison, employee contributions to DB plans are tax-deferred and have become widespread.

Another major reason employers quit DB plans has been the effect of market volatility on their accounting and cash funding requirements. Employers have responded both by shifting to DC plans and by adopting hybrid DB plans that share the risk of market fluctuations with employees. Hybrid DB plans now cover some 40 percent of private-sector workers with DB plans. They could be used more broadly, but as of this writing the final enabling regulations mandated by the Pension Protection Act of 2006 have never been issued, and a cloud still hangs over cash balance and other hybrid designs.

In ERISA, the ‘E’ Doesn’t Stand for ‘Expert’; It Could Stand For ‘Education’

With the rise of individual account savings and investment plans, marketing has shifted to a focus on asset values and investment returns. A multitrillion dollar industry has developed around the notion that individuals can and should be their own actuaries and investment experts. Retirement plans and services are complicated, and virtually everyone recognizes that the average individual is unprepared even to understand them, much less make an informed choice. Nonetheless, we increasingly are imposing responsibility for those choices on those least capable of making them.

We could do better. Robert C. Merton, a Nobel-prize-winning economist, points out that if the goal is retirement income security, then retirement products should be presented and marketed based on the level of reliable retirement income they provide. He noted that part of the consumer reluctance to consider lifetime-income products may result from the fact that their choices are presented in terms of investment returns, rather than either retirement income or reliability.

Thus far, however, there is no such standard disclosure. Despite the fact that two separate government agencies regulate disclosure, purveyors of 401(k)s and IRAs are not even required to provide such information, much less explain it. Instead, bewildered individuals get a combination of soothing messages and glossy pamphlets, accompanied by the required-but-incomprehensible disclosure forms.

Putting ‘Income Security’ Back in ERISA

Although the entire purpose of ERISA was income security, all the trends since then are headed the other way. What were once lifetime- annuity retirement plans marketed to company human resource departments are now investment accounts mass-marketed to individuals. The average person doesn’t understand annuities, and many don’t trust the insurance companies that offer them or the people that sell them. Sometimes, income security isn’t even part of the conversation.

Public policy hasn’t helped. It’s widely recognized that government policy increasingly favors DC plans over DB pensions—but even for DC plans, public policy favors those that have no annuity purchase component over those that do. Additional fiduciary requirements are imposed if a plan sponsor chooses to add an annuity purchase option, rather than merely relying on a collection of mutual funds.

This bias against lifetime income isn’t limited to DC plans. Even for the 40 million US workers who participate in private-sector DB plans, public policy works to undermine retirement income security.

Traditionally, when companies decided to eliminate their pensions, they would purchase annuities from an insurance company, thereby preserving lifetime income. However, because the lump-sum valua- tion rules do not take current market conditions into account, companies now save 10 to 15 percent every time an employee chooses a lump sum versus a comparable annuity. Even more sadly, because of the failure of one insurance company 30 years ago, advocates sometimes devote more criticism to annuity purchases than to the epidemic of lump sums.

We’re from the Government…

Sadly, much of the legislation since ERISA has led employers away from providing income security. It started soon after ERISA, when the Revenue Act of 1978 provided more flexible tax treatment for IRAs. Subsequent legislation either tightened restrictions on DB plans or loosened restrictions on DC plans.

The government agencies charged with enforcing ERISA and other retirement laws care about retirement security, but the ways they’ve interpreted the law have frequently undermined it. Instead of allowing companies and plans the flexibility to adjust to changing preferences and finances, they’ve often declined to use their discretion, or just haven’t acted at all.

Many would say that the agencies who enforce ERISA have largely given up on DB and traditional pensions. Rather than work to pre- serve DB plans and sponsors and the 75 million people that have them, they are focusing on 401(k)s and IRAs. As a result, the incentives to switch from a DB plan that offers lifetime income to a DC plan that doesn’t is growing.

ERISA Should be Reformed, Not Retired

Nonetheless, there is plenty of room for change and for hope. There are many examples that we can adapt from other nations, from state governments, from private companies, and from such financial firms as TIAA-CREF. And there are plenty of people of goodwill working to do so. The list below is far from exhaustive.

Preserve Existing DB Plans When Possible

The most urgent issue we face is that some multiemployer pensions are in severe trouble and, absent legislation this year, plans covering more than one million people will almost certainly fail. Long before they do, employers will decide to abandon multiemployer plans, initially individually, then by mass withdrawal. By then the die will have been cast, and future congressional or PBGC action will be too late to avoid the collapse of multiemployer plans generally. Fortunately, members of Congress from both parties are working with both business and labor to develop a compromise set of reform proposals, as they did in the Pension Protection Act eight years ago.

There are other ways to preserve pensions. Members of Congress from both parties have recognized that most employers are better suited to be “conduits”: to facilitate access to plans than to be fidu- ciaries for them. They have proposed to expand the availability of “multiple employer”4 plans.

Even without waiting for legislation, there is much that the ERISA agencies could do to facilitate these efforts and to provide more flexibility generally for those that offer DB plans. For example, the Department of Labor (DOL) could facilitate the creation of new multiple employer plans, and Treasury could issue its long-delayed regulations to clarify the rules for hybrid plans.

Other Actions to Improve Retirement Security

There are also many ways to improve retirement security by providing lifetime income without DB plans. Within the legal structure of a 401(k) or an IRA, one could expand both their coverage and the extent that lifetime income as part of the structure. DOL could create a safe harbor for annuity purchase within 401(k)s and require (or at least facilitate via a safe harbor) uniform disclosure of lifetime income.

Members of Congress from both parties have suggested encouraging automatic enrollment and automatic escalation. At the federal level there is currently no consensus and the proposals have not advanced. However, states across the country are considering developing their own programs, considering whether to expand retirement coverage by requiring businesses to provide a payroll deduction “secure choice” retirement program from which employees can opt out. California enacted enabling legislation5 and more than 15 other states have begun study efforts.

Mid-Life Crisis—or Mid-Course Correction?

What ERISA needs is not a mid-life crisis but a mid-course correction. ERISA’s “crisis” could be the wake-up call we need. The same creativity that created ERISA a generation ago can provide retirement income security for the generations to come.

Notes

1. Gallup Poll Social Series: Economy and Personal Finance (April 2014).

2. In On Death & Dying (1969), Kübler-Ross postulated the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

3. The market crashes of 2008–9 affected, but did not reverse, this preference.

4. The similarity in name to the very different multiemployer plans adds to the confusion with which retirement policy discussions are already rife.

5. The California Secure Choice program is subject to legislative re-approval after development of an operating plan.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

ERISA @ 40: A Midlife Crisis

October 29, 2014