In episode 5 of Quite By Accident, Steve Hess shares with host Katie Dunn Tenpas his feelings on his close friendship with Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Steve also recounts how, through a series of fortunate connections, he got a job in Nixon’s White House, what he did there, and his feelings about Nixon and Watergate.

- Listen to Quite By Accident on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Watch on YouTube.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Thanks to: Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, senior producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video editor; Colin Cruickshank, videographer; Katie Merris, art designer; Tracy Viselli and Adelle Patten, Governance Studies communications.

Transcript

[music]

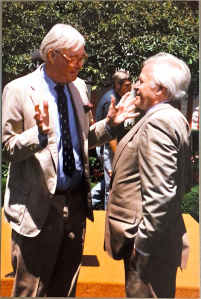

TENPAS: I hope you have a friend in your life who means as much to you as one friendship in particular meant to Steve Hess. It’s a person you’ve probably heard of: Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Moynihan had an illustrious career in public service to the nation: Navy veteran, assistant secretary of labor, ambassador to India and to the United Nations, Harvard professor, and U.S. senator from New York for 24 years. A staunch Democrat, Moynihan was also, surprisingly, a close advisor to Republican President Richard Nixon.

[music]

I’m Katie Dunn Tenpas, a visiting fellow and director of the Katzmann Initiative at the Brookings Institution, and a practitioner senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. In this episode of Quite by Accident, you’ll hear about Steve’s friendship with Moynihan, which started before Nixon finally won the presidency in 1968, continued in the new administration, and stretched beyond.

HESS: Moynihan in the early Kennedy administration was the assistant to Arthur Goldberg, secretary of Labor, and Goldberg was a family friend. And Goldberg, if you knew Goldberg, had decrees and he really sort of decreed that the two of us were gonna be friends.

And subsequently we were both at Cambridge. He had come back and run a program at Harvard-MIT program. And I got a Kennedy Fellowship at Harvard. And it just seemed this was a time to talk. And once we talked, we never stopped talking. It was the most natural friendship of my life.

TENPAS: Steve and Pat Moynihan, who died in 2003 at the age of 76, did indeed remain lifelong friends.

HESS: And we’d do marvelous things together. I mean, on their 40th anniversary Pat and Liz say, come with us to Turkey. Gee, I don’t know. Come with you to …. Oh, no, no, no. Come with us to … his wife is an archeologist. We’re gonna see great digs in Turkey. So, we go with them to Turkey.

Or, we’re taking the kids up to, to, to look at colleges. He says well stay with us in upstate New York. And we, we go up to their farm in upstate New York. And Pat will say to our kids, Young Americans, go out and pick the corn for dinner. And so they go out and pick the corn … we’re constantly having these experiences.

[music]

Or when he is the senator, he’ll call and I say, it’s July and you’re telling me to come out for a picnic, and it’s, it’s 90 plus degrees. He said, don’t worry, get your sandwiches. Meet me. And it turns out he has found a grotto in the middle of the Capitol grounds. And he could get in the grotto and we could sit in the grotto in the cool, drinking our wine and eating. It was always like that with Pat and Liz.

TENPAS: It’s a magical relationship.

HESS: It was a magical, we didn’t contribute much, but it was always that way. I’d get home and there’s a box in front of me and, What’s the box? It’s a huge flag that has just flown over the Capitol. What am I gonna do with a flag that’s as big as this room?

So, I take it back to Brookings and I look around—nope, Brookings doesn’t have a flag, and I say to the president of Brookings, you put up a pole and I’ll get the flag. And so, sure enough, we now have a flag in front of Brookings because Pat does constantly.

TENPAS: And it’s the Pat Moynihan flag.

HESS: I guess by now it might be some other flag cuz that was a long time ago. But, God, he was just so engaging.

TENPAS: Their friendship actually extended into the Nixon White House, where they worked together after Moynihan was appointed a domestic policy advisor to Nixon. You heard that right, Moynihan, a Democrat, a lifelong Democrat, was appointed by Republican Richard Nixon to serve in his administration. More on that later.

And Steve got his second job in the White House after he had returned to the Nixon camp on the 1968 campaign trail, when he was asked to travel with Spiro Agnew, the vice presidential candidate and the governor of Maryland. The campaign was worried about Agnew’s continued gaffes.

Steve sets the scene by recalling how in 1966 Nixon had asked Steve to come work for him in New York. Steve had said no because he was working on his books and was really happy staying in Washington, D.C.

HESS: When I said “no” to Nixon in a sense that ended my serious relations with Nixon. I subsequently coauthored a book about Nixon.

TENPAS: Nixon: A Political Portrait, with Earl Mazo.

HESS: But when we got to Miami Beach and in ‘68—

TENPAS: —Miami Beach was the site of the 1968 Republican National Convention—

HESS: —I had nothing to do with the convention and stayed out of that until a strange thing happened. He chooses somebody named Spiro Agnew.

TENPAS: To be his vice president?

HESS: To be his vice president. And Spiro Agnew starts with a series of gaffes that are just outrageous. And I’m at Harvard, and I get a call from Bob Haldeman. And he says, R.N. wants you on the plane with Agnew. R.N., Richard Nixon, wants you on the plane.

[music]

And I make a few calls to make sure that I was going on the plane with a crook as governors of Maryland tend to be. But I find that that’s true. He’s not a crook at that point.

TENPAS: Not at that point, indeed. Spiro Agnew resigned as vice president in 1973 after pleading no contest to a felony charge of tax evasion after a criminal investigation. Nixon picked House Minority Leader Gerald Ford to replace Agnew. Vice President Ford of course became president when Nixon resigned just one year later. But back to the campaign trail, 1968.

Note that in this section, Steve relates how Agnew used derogatory language, and we have bleeped these words throughout.

HESS: So, I’ve agreed to go on the plane. We go 60,000 miles together. And we’re flying from Dallas to Cheyenne. And he’s been using a speech that somebody gave him, which is sort of an interesting speech about population explosion and what you could do for population explosion. But of course, Wyoming has the smallest number of population of any state.

HESS: And so, I walk up to his part of the cabin and sit next to him. It’s evening, you can look out, you can see there’s a light there, way over there other light and so forth, people down there. And I said, Mr. Vice President, I don’t think that speech on population dispersal is right for this. He nods. We go into Cheyenne to the auditorium. The bands are playing. It’s a big deal for Cheyenne. And he gives the population dispersal speech.

And I’m stunned because I’ve just joined his staff. And there’s really only about the second speech I’ve written for him. And I go back and what have I got myself into?

And his assistant comes and says, the governor would like to see you. So, I go over to see him and he’s sitting there, comfortable chair, and he’s got papers all over the floor. And he looks up and he said, Steve, I picked up the wrong speech. And I think to myself, I’m sad, this is too bad, but your job is to pick up the right speech.

So, again, I keep writing speeches for him. He does send them out to the press each day, which they don’t use because they know he’s not going to deliver them. And he just says what he wants to say off the cuff. But he can’t fire me and I’m not going to quit. And so we go through this thing together.

TENPAS: … kind of a charade.

HESS: Yeah.

TENPAS: And why do you think he’s so reluctant to use your speeches?

HESS: Well, he he, he doesn’t like to read. He reads …

TENPAS: Oh, he just likes to talk … extemporaneous

HESS: Yeah, he likes to talk. And he keeps making mistakes. He gets to Chicago, big Polish population. And he calls people “Polacks.” Going to Hawaii, he’s got a reporter on the plane. He said, Hey, what’s with the “fat Jap”? I mean, he’s saying those wrong things. It’s a disaster with this man.

So, at any rate, there I am with him all the way. They send Pat Buchanan for about a week and he loves Pat Buchanan, Pat Buchanan loves him. But at any rate, the campaign is over. Nixon wins. That night I go to the state house in Annapolis to say goodbye. I fly immediately to New York to be with the Nixon people.

[music]

And if I want a job, a good job in this administration, hey, they owe me. I have been 60,000 miles traveling with this man.

TENPAS: It turns out, Steve had a pretty good idea that Nixon would win the election even before the 1968 campaign, and in that story you’ll hear a familiar name: Henry Kissinger.

HESS: Oh, Kissinger. Yeah, we were always around one way or another. Before the ‘68 campaign, I was at Harvard, as Kissinger was, and we were invited to debate before the high school students in Boston. Big audience.

TENPAS: What was the topic?

HESS: Who should be president. He’s got Nelson Rockefeller. I have Richard Nixon. And we’re going to debate this before all these 16-year-olds. First thing that surprised me that that Kissinger was sort of nervous. I guess he didn’t talk much to 16-year-olds.

But I although I didn’t know Kissinger very well, I thought very highly of him. And I had always been doing things like giving Nixon articles by Kissinger, I wanted him to feel good about what Kissinger stood for so that he would never put it as a position to cut it off so he couldn’t have him when he gets president.

So, it was sort of funny. In this debate, and I know I’m going to win the debate because I thought about it and I thought, what’s the one issue that I can win over these kids? And the one issue was that Nixon was against the draft.

But when the issues came up on foreign policy what I did was turn to Kissinger to answer the question. The kids are very confused by this, but this is part of my strategy about keeping Kissinger in the fold. And we don’t see each other until Miami, the convention.

TENPAS: In 1968?

HESS: In 1968. And it’s funny, we were in one of those grand hotels. And I remember Kissinger going up on an escalator and I’m going down on the other side of the escalator, and he calls out to me, “Rockefeller in three.” And I laugh because he couldn’t be more wrong. He thinks Rockefeller’s going to win in three when I know Nixon’s going to win on the first ….

TENPAS: Ballot, so he meant three ballots?

HESS: Yeah, that’s what he said. “Rockefeller in three” and so forth and so on.

TENPAS: Nixon won the GOP nomination over Rockefeller, New York’s governor, on the first ballot. And then, as noted, won the main contest over Humphrey. Steve would meet up with Kissinger again in the White House.

HESS: Later, Nixon is elected and not only we’re both at the White House, we’re both on the ground floor sort of all of us looking at each other. And he’s in the Situation Room, and I’m around the corner with Moynihan. And strangely we go to the men’s room at about the same time every morning, Kissinger and I. We’re standing at urinals next to each other. And he sort of bends over and he says, “Steve, you were right. This was the right moment for this man in history.”

[music]

Well, if you tell that with a German accent, it’s very funny.

TENPAS: And so, as he said earlier, Steve thought the Nixon camp owed him something for traveling with Agnew on the campaign trail, and because of his close friendship with Pat Moynihan, Steve had another lucky opportunity.

Remember, Moynihan was a Democrat; both Steve and the new president were Republicans. It’s nearly unheard of today for a president to appoint top people from the other political party, but the impulse to do so has always been a part of our politics. I asked Steve if Nixon was trying to do this in the appointment of Moynihan.

HESS: Not really. What happened was that Moynihan made some speeches, which were against the things that his party had been doing and that were very appealing to him.

TENPAS: What was an example?

HESS: Well, all of the positions that they had set up in the Food for Peace and so forth and so on. Ultimately he thought, hey, stop giving them social workers, give them money. And that was a big theme of his. And that was very appealing. Len Garment put it in front of him, showed him the speeches when he was a candidate. And that was on his mind when he got to that position of choosing people. And he had nobody else to do that. I didn’t propose that.

It was funny, I sent him a copy of my book on Nixon when we were just friends early on, and he had written something like, If you ever change your mind or something to inscribe it to me. But I was not personally promoting him in any way. But others were, like Len Garment and like Bob Finch. So, he had some supporters for that. And the job was open in a sense.

TENPAS: And in a way this is something that today’s listeners find would probably jaw dropping, that a Republican president would appoint a Democrat to be the head of their domestic policy.

HESS: That’s true. But there was a tradition in which presidents tried to pick somebody from the other party to show that you’re above it all. It was always a bad idea. You couldn’t win over the party because suddenly you made Bill Cohen secretary of defense.

TENPAS: William Cohen, a Republican senator from Maine, was appointed by Democratic President Bill Clinton as secretary of defense, and served four years in that role.

HESS: But they always thought that they could. So, there was a tradition of appointing somebody to something from the other party. I don’t really think this was part of that. This was a special thing that Nixon had for Pat.

TENPAS: In fact, Steve wrote a book about the special relationship shared between Richard Nixon and Pat Moynihan—The Professor and the President. Such a great story.

So, think about the domestic policy adviser to Nixon as sort of the counterpoint to his foreign policy adviser, who was then Henry Kissinger, whom Steve had debated just a few years earlier.

And then Moynihan asked Steve to come work for him in the White House.

HESS: Pat is thrilled this is his job, he’s wanted it all his life. He wishes it had been offered by somebody else, but it’s offered by Nixon. And I fly up to New York to see him, but he’s seen Nixon. And we have dinner and have too much to drink. And he says, Come with me. Actually, I really didn’t want to go back to the White House.

TENPAS: Really?

HESS: No, I thought that I’d find some other interesting job somewhere. But first of all, being with Pat Moynihan is going to be a joy. It’s going to be more fun than I’ve ever had, number one. And number two, I think he needs me. I’m probably the only Republican he knows! So, I go with him.

TENPAS: Steve soon found out that Nixon White House was very disorganized, especially when compared to his time working with President Eisenhower.

HESS: It was that the Nixon administration when I was on his staff was the first two years. Eisenhower was the last two years. There’s a difference between first years and last years. And the Nixon administration had a difficult time getting organized. Very strange because Nixon initially said he was gonna organize it like Eisenhower did, but Eisenhower knew how he organized it and Nixon couldn’t fit into that role.

So, the Nixon administration over the years really changed quite often. And in fact, the organization that I was involved in was totally unlike any organization Nixon had ever had. Because he appoints Patrick Moynihan, who asked me to come, and tells him, in a sense, you’re gonna be the head of my domestic—

TENPAS: —policy—

HESS: —operations comparable to Henry Kissinger.

And then he calls in Arthur Burns and gives him the same job. So, it’s a very well-known type of organization where you compete against each other, but had never been a Nixon way of organizing before that.

So, that’s what I stepped into.

[music]

And it was totally unexpected to Arthur Burns. All Arthur Burns wanted to do was be the head of the Fed. But it wasn’t gonna be available for a year. So, when he walked in to give some report to the president, he said, by the way, you’re now the urban affairs director, and he’s already told Moynihan that he was gonna be the urban affairs director. So, they were in competition in an interesting way.

TENPAS: That’s an interesting way to staff a White House.

HESS: It sure was. And it never happened again with, it was a one shot proposition. And it was very uncomfortable as it turned out for the president. It was very strange. There were only about three people who had been on the Eisenhower staff who were now eight years later on the Nixon staff. There wasn’t a big turnover. One of them had been Arthur Burns, who had been his economics advisor for Eisenhower.

And Eisenhower loved him. They sat and talked, but Burns was a long-winded, boring person. And when he now was on the Nixon staff, Nixon couldn’t stand him. Poor man. Same man. He hadn’t changed, but one president loved him and the other president couldn’t stand him.

Of course, he didn’t know Pat Moynihan before. That was a strange reason that he picked him, but he got him. And Moynihan was funny and charming and had stories, and the president had no other experience like that, and he loved him.

To me it was all showed how important these things were and thinking major changes because somebody drops a bomb. But there were major changes because one guy had an engaging personality, and another didn’t.

TENPAS: Arthur Burns did eventually become chairman of the Federal Reserve—early the next year in fact, February 1970. He served 8 years in that role and was appointed by President Reagan to serve as ambassador to West Germany.

[music]

Let’s go back to Steve. Why did Nixon appoint the liberal Harvard professor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, to his staff? Of course, as Steve says, everyone liked Pat Moynihan, but practically speaking, what was it all about?

HESS: So, I explained to him what was Nixon’s strategy. And Nixon, who thought of himself as a moderate—what does a moderate mean? Moderate means you’re in the middle. You know, something comes along, it’s not conservative, it’s not liberal. So, there you are. But that’s not what he meant at all.

And this is what I’m telling Moynihan in terms of you are going to have to operate with Nixon. Moderate meant to him, if I do something tremendously conservative, like appoint a conservative to the Supreme Court, the next thing he’s apt to do will be incredibly liberal. So, you I’m telling you, as soon as he does that, appoint somebody to the Supreme Court, that’s when you strike!

TENPAS: That’s your moment.

HESS: That’s your moment to get what you want liberally.

TENPAS: And did it work out that way?

HESS: Yes, it worked out that way. But now we’re starting to talk about how about Nixon. I mean, that’s starting to define him.

[music]

And so some people have written books about Nixon as the conservative, some people have written books about Nixon as a liberal. And I’m saying Nixon was whatever the politics seemed to demand to him at the time.

TENPAS: So, it’s 1969, Steve was in the White House working for Moynihan in the domestic policy office, not as a speechwriter as he had been a decade earlier. Who were the speechwriters?

HESS: His ultimate dealings with speechwriters was not to have one, not to have two, but to have three. And they were very good men. One is Ray Price, who’s a liberal, who had been the chief editorial writer of the New York Herald Tribune. The other is Pat Buchanan, who we’ve already talked about, he’s conservative. And the third is Bill Safire, who wrote the wonderful books about words and things like that. And he’s the one who will find good stories to tell and so forth.

So, again, it comes back to that position that there was no Richard Nixon, there were three that had to be blended somehow, even though he could have done it otherwise.

TENPAS: At the end of that first year of the Nixon administration, Steve was in the middle of another reorganization.

HESS: What happened, the White House was being reorganized in 1969. Moynihan was being made a cabinet minister without portfolio, which he rather liked. There are lots of things he could do. And his commitment was to only stay two years to get back to Harvard. If he stayed longer, as Kissinger did, he would lose his Harvard job.

And most of the young people on Pat’s staff would either stay or they go back to law school or something like that. The question was what the hell they could do with Steve Hess? They were always a bit uncomfortable because he was the liberal anyway.

So, I went into the Oval Office, not knowing what they were going to give me. They had offered me an ambassadorship to a small African country, Peter Flanigan, who handled high level appointments. And people love that, boy you’re called Your Excellency for the rest of your life. And I said, Oh, heavens, I don’t know anything about that. I have a mother who’s ill. I have small children. What am I doing with that? So, I said, thank you very much.

And then I’m in the Oval Office, and Nixon starts to tell me how unhappy he is with how HEW—Health, Education, Welfare—is being run by Robert Finch. Robert Finch is his closest friend in the cabinet. He had been his campaign manager in 1960. He would like to have had Robert Finch as his vice presidential candidate. So, he puts him in this position and it’s not working out at all. And it’s very awkward. And he says things to me in sort of a way that I’d never heard him speak before, as if he’s really so sad about that.

And he says to me, I want you to go over and see if you could straighten it out. And it was literally one of those times you almost see in movies where you open the door to leave and you turn around and you say, How the hell could I do that? He hasn’t told me how to do it, what he wants.

Now, I don’t know if that was an easy way to get rid of me or not, but when I get over and I don’t know what to do because Finch and his deputy Veneman are really good friends of mine, I’m not opposed to them. And I can’t really say to them, the president thinks you’re failed.

And so, that’s when they say to me, won’t you become the head of the White House Conference on Children? And I said, Oh, my God, we’re in the middle of a war. And you’re telling me to be in charge of America’s relations to youth. They said it’ll only be a year.

All right, I’ll do everybody a favor. I’ll do that. And then, of course, when I get there, I realize within moments that I can’t have a conference on both children and youth because everybody will be screaming about Vietnam, about children’s things, about youth things.

[music]

But there were terribly important questions of children that I didn’t want to block. So, I had to go back to the White House and tell the president, separating them if you would. What did he care? He did it.

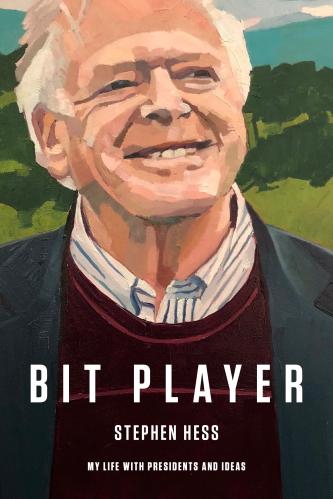

TENPAS: Steve ran the White House Conference on Children in December 1970, and then the White House Conference on Youth in April 1971. You can read about his experiences in his book, Bit Player.

HESS: So, then I do that somehow and survive it. And I go back to the White House. I’d still like a job. But, you know, Len Garment said there’s lots of jobs in government. But the truth of the matter is there aren’t lots of jobs that you might like at that moment.

And I look through them and he says, Well, how about the national chairman of humanities. So, I said, yeah, that would be sort of interesting. So, he readied to put up my name for that.

TENPAS: It was the Senate confirmed position?

HESS: Senate confirmed position. And the official humanities organizations, the historical society and so forth, they come down on me like a ton of bricks. He’s not qualified for that! Headline in The New York Times, “Hess not qualified!” And so forth. And I say, Well, I’m sorry about that. I asked them to read my books and they wouldn’t read them. I asked them to interview me on what I wanted. They wouldn’t listen to me. So, I’m sorry. We can’t do this.

TENPAS: Steve’s time in the White House was drawing to an end. Two years at the end of Eisenhower, two years at the start of Nixon, one a bit more chaotic than the other.

HESS: And what you know because you’ve studied the presidency the same way as well, is that each year is different. We can write about the presidency of Eisenhower. But there’s a first year president, that’s how the president sees his job in the first year, second year, the third year, and so forth. So, it was a very different situation, being there.

With Nixon, it was the beginning of some serious chaos, and some of it quite contributed chaos. For example, after he’s appointed Pat Moynihan as his domestic adviser, he suddenly appoints Arthur Burns as his urban domestic, domestic urban. In other words, he put them both in conflict. If you talked about that year, it was a year of conflict.

With Eisenhower, who knew how to run a staff anyway, and by the seventh and eighth year everybody knew where they were, knew their positions in it, and were also by this time older. And with Eisenhower, unlike so many presidents since, there wasn’t this sort of second year churn, wasn’t second year and I either I got a great job offer to be on TV or to be a lawyer or to be a lobbyist and so forth. These people stayed for a very long time, many of the key people for all eight years. But most of them for six years. So, I was with a different sort of person in a different situation. So, it was really very hard to compare the two in that regard.

TENPAS: And remember, prior to serving as president, Eisenhower had commanded allied forces in Europe. How did that inform managing his White House staff?

[music]

HESS: Eisenhower knew how to run a staff. Remember, he had run a big one. So, when he had a chief of staff, it was modeled on the same sort of son-of-a-bitch chief of staff he had had when he was in London, trying to win a war. That person was Sherman Adams.

But people on his staff very often tended to be professional. Jim Haggerty, his press secretary, had actually been press secretary twice when Tom Dewey ran for president. He wasn’t starting that way. Jerry Persons, who was a major general, who had replaced Sherman Adams when Sherman Adams had to leave, had run Pentagon’s relations with Congress during World War II. So, there he was running the relationship, and his assistant Bryce Harlow took over. So, he had a one group who were really professionals. And I thought that was that was quite different.

The Nixon staff, you we were often attacked for people who had never even been in the White House. Bob Haldeman came from an advertising agency in California. So, they were a very different, the types of people were very different in terms of their experience in Washington, and their experience running any operation.

TENPAS: In January 1972, nine months before Nixon would easily win reelection over George McGovern, Steve ended his service in the White House.

HESS: I had left the White House in ‘72, before all of this, which meant I had taken my wife and my children to say goodbye to the president. The president is always awkward at these sorts of things. He has a lot of little trinkets, gifts that he gives people, tie clips and cufflinks and so forth.

But then he says to my 8 year old, we’re in the Oval Office, he says, What was your favorite subject in school? And Charlie says, Geography. Surprised me. Nixon’s eyes light up and he says that was my favorite subject, too. And so, he takes my son and they walk around the perimeters of the Oval Office just so he could show Charlie all the different gifts he’s gotten.

And by the way, the helicopter is spinning right outside, you can see it right through the window because we’re spending too much time, and they’re supposed to be flying Nixon to Andrews Air Force Base to fly to Canada to meet Trudeau. And Nixon has now got my two children there. And he says, I want you to see as much of the world as you can. He says even if it’s going to cost a lot of money.

And then he starts to illustrate this. He starts pretending that he’s walking up or down a gangplank to a cruise ship, sort of. And this is sort of funny. It’s actually, Nixon’s funny and the kids are laughing and that’s it. They go out the door. He goes off to Trudeau. We go back home.

TENPAS: And that was it. That’s the last time you ever saw him?

HESS: That was the last time I ever saw him. Right. Yeah.

NIXON: “And I want to say this to the television audience: I made my mistakes, but in all of my years of public life, I have never profited, never profited from public service—I earned every cent. And in all of my years of public life, I have never obstructed justice. And I think, too, that I could say that in my years of public life, that I welcome this kind of examination, because people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook. I’ve earned everything I’ve got.”

[music]

TENPAS: In June 1972, five men were arrested after breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C. Over the next two years, House and Senate investigations uncovered President Nixon’s knowledge and coverup of the break-in, leading to his resignation in August 1974 in the face of what might have been certain impeachment.

HESS: The Watergate scandal was such a collection of really stupid, outrageous things that no one who had run for president and was a politician would ever go through. Except he ultimately allowed it to happen. And he allowed it to happen because the ultimate goal was being president of the United States, even though at that point he was president of the United States. And even though he was going to get reelected, he was certainly had a strong hold on that election in ‘72. He wasn’t going to get defeated, Watergate or not Watergate.

My position on that was a difficult one because of course, Nixon was my friend. I waited there to find out what happened. Who was responsible for this? Remember, we’re having hearings, Watergate hearings. And day after day, we’re listening to these assistants tell their stories. But we still don’t know what Nixon’s role was. And I’m watching them every day because I’m the analyst on the McNeil-Lehrer Show.

TENPAS: And by then, are you at Brookings?

HESS: Yes, I’m at Brookings. And McNeil-Lehrer have two people sitting on either side. One does the legal stuff and the other does the political stuff, and the political stuff was me. And I’m listening to these people telling outrageous stories, those stories about things like breaking into a psychiatrist’s office. And finally, I tell them that I can’t go on with this. I’m going to resign. I won’t be back tomorrow.

TENPAS: Like, you can’t comment on it anymore.

HESS: I can’t live with this myself.

[music]

And so, I leave. And by this time, something like 74% of the American people are watching this. And I’m there, the one focused on it. And I’m having to tell them about these awful things that are happening. And I really felt I had had too much.

But I still didn’t know the answer.

TENPAS: In 1971, Nixon had installed a recording system in the Oval Office, a fact he kept from congressional Watergate investigators until the secret was revealed in July 1973. But Nixon refused to release the recordings.

HESS: And the answer came when the Supreme Court finally said, We’ve got to release the tapes. And they released the tapes and virtually the next day it’s clear that Nixon knew about it and he resigns.

TENPAS: Did you have any contact with people during that period in the White House?

HESS: No, no, no, no. I. I wouldn’t … no.

TENPAS: What about, like, the former the people who were involved with Nixon formally? Like, were you guys talking on the phone saying, can you believe this or …?

HESS: No, no, I was totally separated. No, I didn’t.

TENPAS: Were you in disbelief from the start? Did you think, Oh, this is just some sort of …?

HESS: I did not know. In fact, I gave a talk at Harvard Business School during that period while we were sort of waiting, and I put forth every reason why I thought Nixon didn’t know. They were good reasons. The president of United States doesn’t usually know about that sort of thing. This is a president involved in international affairs. I probably had three or four different reasons why it couldn’t be Nixon. So, that’s how I responded.

And then, of course, it turned out that all my reasons were dead wrong. Nixon did know.

TENPAS: And did you ever talk to him subsequently?

HESS: No. Pat Moynihan said, You’ve got to make closure with Nixon. I mean, you’ve been so close to him for so long. And he said, I’ll call him up. And we both go up to—Nixon was now living in New Jersey—we’ll go up and we’ll have lunch and you’ll have some closure.

And I waited till after Nixon’s memoirs came out. And he admitted no wrong for these crimes. He said merely, I’m sorry that we let down the American people.

[music]

And that might have been good enough for David Frost, who was making quite a living off these tapes, but it wasn’t good enough for me and that was closure. Nixon had sent me a book. I didn’t acknowledge it, and I didn’t even go to his funeral.

TENPAS: Oh, wow.

HESS: I was that removed and that hurt. Now, that’s all of that says a lot about me that may be awful. But that’s how I responded.

TENPAS: Steve recounts the Watergate story and his thoughts about the key players in his book, Bit Player.

In the next and final episode of Quite by Accident, Steve goes to Brookings, and keeps finding ways to serve the nation.

[music]

Thank you for listening to Quite by Accident, a podcast from the Brookings Podcast Network. I’m Katie Dunn Tenpas at Brookings and the University of Virginia.

I’d like to thank Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, senior producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video editor; Colin Cruickshank, videographer; Katie Merris, who designed the cover art; and Tracy Viselli and Adelle Patten from Governance Studies.

A very special thanks to my dear friend and colleague Steve Hess.

Additional support for the podcast comes from colleagues in Governance Studies and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastEpisode 5: Moynihan, Nixon, and Watergate

December 14, 2023

Listen on

Quite By Accident Podcast