The dying embers of the COP30 in Belem, Brazil, may well have sparked new energy in Johannesburg, where South Africa appeared to have snatched a passable G20 outcome from what many expected to be certain despondency. But not on the issue of Third World—especially African—debt. Activists left sorely disappointed.

Africa’s debt situation has, in recent years, moved from dire to desperate. It is unsurprising that major reports commissioned ahead of the G20 Leaders’ Summit, such as the Trevor Manuel Report (disclaimer: this writer contributed), have all placed the “debt crisis” at the center.

While a sustained campaign is critical until the best ideas are implemented, there are times when well-intentioned advocacy risks demonizing debt itself. Such moral overcorrection can misdiagnose the real maladies and prescribe the wrong remedies.

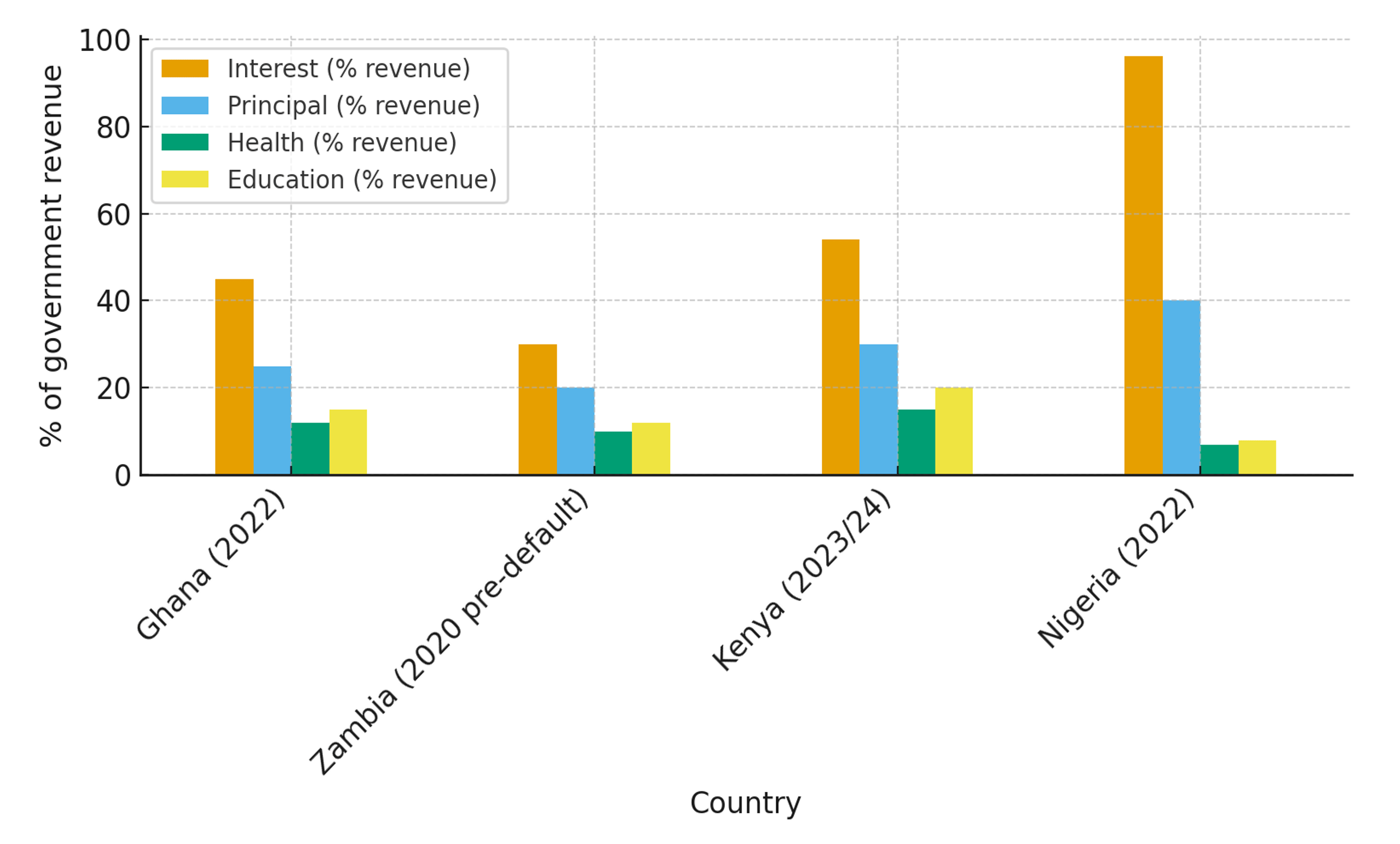

One familiar refrain: “African governments spend more repaying debt than keeping citizens healthy or educated.”

Debt Justice, a British campaign group, for example, often points out that many African states spend more on external debt service than on healthcare. It has described the international financial system as “rigged in favour of creditors.” Oxfam, an important global NGO, warns that “debt repayments are draining resources that should be used to tackle hunger, education and health.” Christian Aid argues that the system is “exploiting Africa by demanding debt repayments that cost lives.” Even U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres told African leaders in Nairobi in 2023 that “Africa is being strangled by debt” and that governments now spend more on debt than on essential services.

Such assertions would usually be backed by a graph similar to the one below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Debt service vs social spending (selected African cases) Source: Author’s compilation. Data from International Debt Statistics and national budgets.

Source: Author’s compilation. Data from International Debt Statistics and national budgets.

Breaking down ‘debt service’

These earnest campaigners and leaders all have a point, and their motives are undoubtedly humanitarian. But several nuances and caveats warrant greater attention.

Most claims about debt rely on the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics (IDS), which defines “total external debt service” as the sum of interest and principal repayments made in a given year. Campaigners then directly compare this combined figure with education or health budgets.

Yet according to the U.N. System of National Accounts (SNA 2008) and the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics Manual (GFSM 2014), interest is an expense, but principal repayment is not. Principal is a financing transaction. Think of it as a balance-sheet swap, rather than expenditure. Comparing principal plus interest is like equating a mortgage repayment with buying groceries: It confuses financing with consumption.

For the layperson, the simplest way to understand this is to consider the principal part of the debt service as a simple return of the money African governments took from investors to invest in things like health and education. To characterize this repayment as proof that Africans are being systematically ripped off stretches the idea of exploitation much too loosely.

The analogy of Africa as a startup helps explain why principal flows can sometimes look so large. Young firms borrow short, roll loans frequently, and dedicate large cash flows to debt service, all because they invest upfront to reap benefits later. African governments must also borrow to build the hospitals and schools where health and education services are provided. These refinancing dynamics inflate total “debt service” numbers, but they do not necessarily mean resources are being diverted from essentials at the scale implied.

Like startups, the core question is whether debt liabilities are financing productive assets: infrastructure, human capital, and institutions.

The OECD parallels

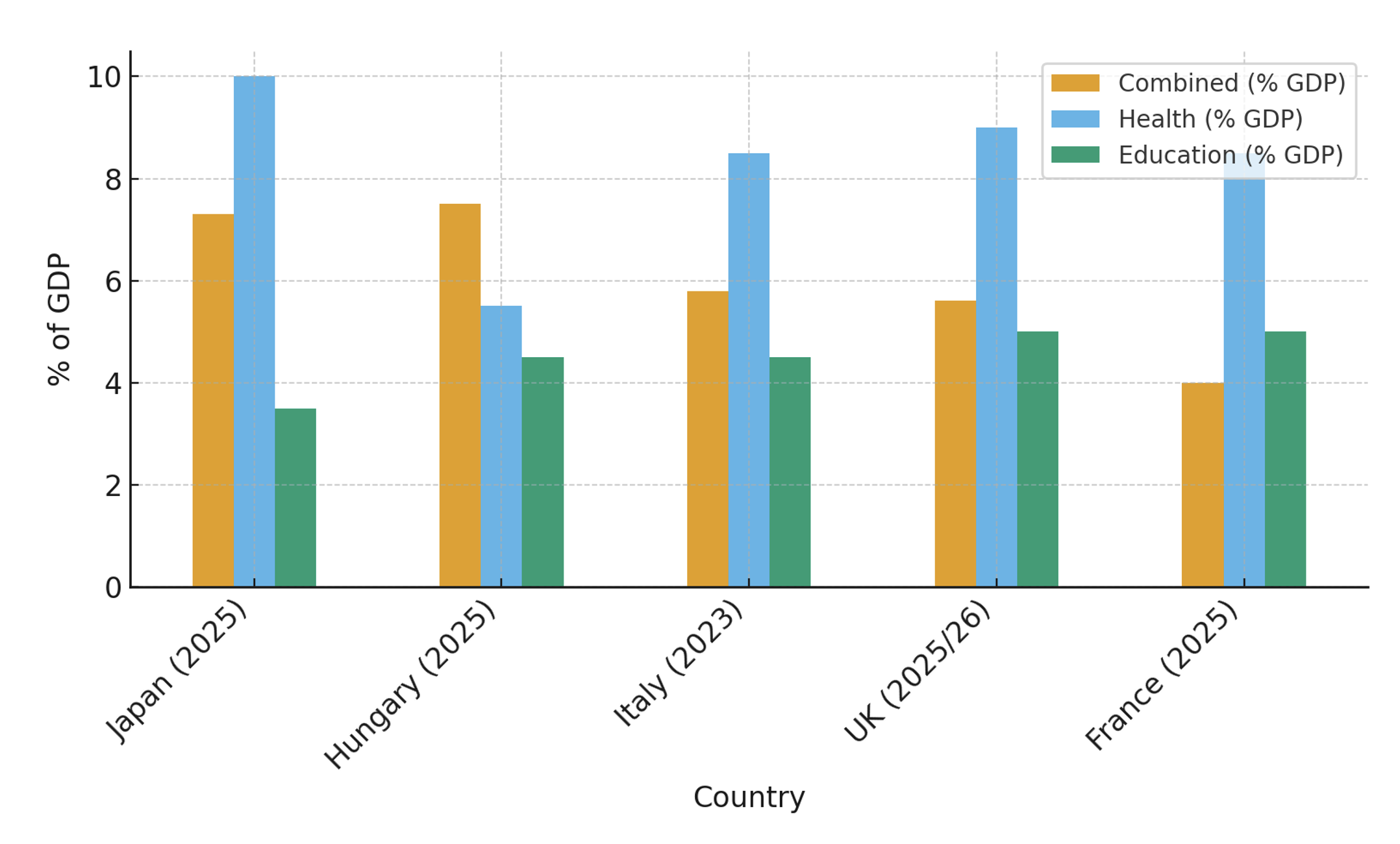

If activist applied their preferred metric—i.e., principal plus interest compared to health and education spending—to some richer countries, the results would surprise them.

Japan’s FY2025 budget sets aside ¥28.2 trillion for “National Debt Service,” of which ¥10.5 trillion is interest and ¥17.7 trillion is principal. This is equivalent to about 7.3% of GDP, and significantly larger than the entire education budget.

Hungary’s 2025 financing plan anticipates HUF 8,715 billion in redemptions, alongside interest equal to 5% of GDP. A combined amount of 14.6% of GDP, significantly exceeding Hungarian spending on education and health together.

Italy, too, with interest near 3.8% of GDP and large redemptions, could, under activist framing, be portrayed as prioritizing creditors over citizens.

Yet few would argue that the international financial system “exploits” Japan, Hungary, or Italy. The activist framing, applied consistently, would turn some mighty OECD potentates into objects of pity.

Figure 2. OECD: Total debt service vs health and education Source: Author’s computation and charting from the International Debt Statistics database and national budgets.

Source: Author’s computation and charting from the International Debt Statistics database and national budgets.

Yes, interest repayments are a burden for some African countries

The genuine fiscal strain in Africa is interest payments.

- Ghana’s interest payments consumed more than 45% of revenues in 2022.

- Nigeria’s interest bill in 2022 was nearly equal to its entire federal revenue base.

- Zambia, before its default in 2020, projected interest to exceed 50% of revenues (having hit 44%+ by 2019).

Unlike principal, which can be refinanced, interest drains real resources. This reflects Africa’s high cost of capital. Eurobond spreads of 800 basis points or more were common between 2022 and 23, while Germany’s borrowing cost approached zero.

That is why the Trevor Manuel Report focuses so much on compressing Africa’s cost of capital.

Activists and campaigners would do well to tighten their critique: The real issue is not that Africa repays principal, but that too often, the interest rates are too high, and the borrowed funds often fail to deliver.

The IMF’s Public Investment Management Assessment finds that inefficiencies reduce the impact of public investment in low-income countries by around 30%. Roads deteriorate early, power projects stall, and brand-new hospitals can’t open because there is no staff. Consider the Agenda 111 hospitals in Ghana, where after $400 million or so spent, and another $100 million in validated arrears, not a single clinic is functional due to poor prioritization and policy-synchronization (a problem the author elsewhere calls “katanomics”).

High interest rate is exacerbated by domestic factors

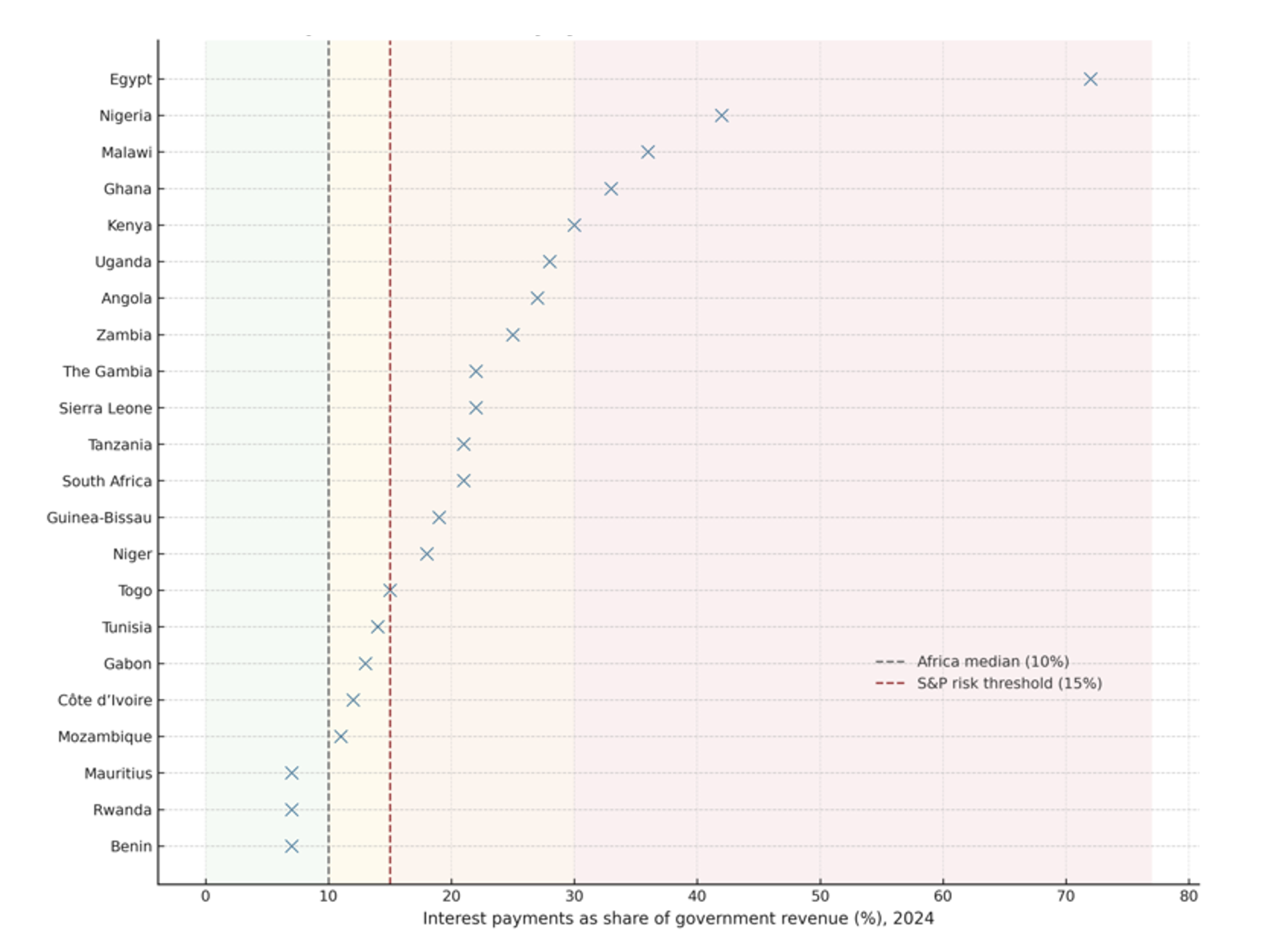

The point here is that even high interest rates by themselves don’t automatically result in debt distress. Domestic-level efficiencies in the use of commercial debt magnify the problem, creating outliers like Egypt, Ghana, Nigeria, and Malawi.

Figure 3. Spread of interest payments as a share of revenue in Africa Source: Author’s compilation from the World Economic Outlook.

Source: Author’s compilation from the World Economic Outlook.

When “domestic heterogeneity” is taken into account, the data reveal several “positive deviants” in Africa that perform on par with some OECD countries in the metrics of debt restraint and affordability.

Figure 4. Interest vs education spending in selected African countries Source: Author’s computation and charting from the International Debt Statistics database and national budgets.

Source: Author’s computation and charting from the International Debt Statistics database and national budgets.

In fact, Africa actually doesn’t borrow enough

Despite the moral panic of debt overload and distress, the real challenge is under-leveraging in Africa. According to UNCTAD, Africa holds just about 2% of global public debt, significantly lower than its share of global GDP. IMF numbers show that low-income countries have debt-to-GDP numbers that are a mere quarter of advanced economies.

While campaigners like to mention that Africa’s debt-to-GDP is between 55% to 60%, this is the lowest among world regions, ignoring Oceania. Advanced economies average around 300%.

Moreover, Africa’s corporate and household debt levels (usually below 15% of GDP versus around 100% of GDP in advanced economies) signal extremely limited access to finance.

The debt crisis in specific African countries obscures a bigger picture of low access to quality debt in most African countries.

A neglected contributor to the cost of capital

Because Africa’s infrastructure base is so thin, economic progress often requires the synchronized development of multiple assets. Every development issue thus becomes a “corridor finance” problem.

Most funders, including development finance institutions (DFIs) and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), lack specialized tools for syndicating operators and standardizing financing packages for these types of corridors. As a result, vast opportunities are truncated by stranded projects, artificially inflating perceived risk as investors leave with a bitter taste in their mouths. The high-risk perception persists even when projects that do proceed to completion and operation show higher returns than in other regions. Activists would do well to focus on this problem.

One assessment concluded that only 10% of projects reach financial close. The 90% of project developers who experience such pain naturally cannot be expected to become ambassadors for the African opportunity boon. This, in turn, feeds the high-risk premium activists seek to lower.

Campaigners should continue to campaign for fair treatment. But they should be careful not to overplay the victimhood narrative and end up de-marketing Africa as a hopeless continent only fit for global handouts.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Don’t throw away the debt baby with the crisis bathwater

December 5, 2025