Fake news, conspiracy theories, the shuttering of local newspapers, COVID misinformation, and the erosion of basic trust in scientific facts increasingly distort our public debates. There are many explanations for these phenomena, ranging from the public’s increasing reliance on social media as a news source to media business models and the nano-second news cycle. Yet these factors do not explain why some people and places are so much more vulnerable to misinformation than others. Misinformation has consequences, not only for our democracy but also for our mental and physical health: New research suggests that there are strong linkages between vulnerability to misinformation and despair.

Despair is, most simply put, lack of hope. Despair describes the plight of the many that are ambivalent about whether they live or die. The latter impacts risk taking, as in behaviors that jeopardize health and longevity. Entire communities can experience this helplessness, especially when they are confronted with difficult choices and change. Drug use and suicide are internal expressions of this, while expressed misery, frustration, and anger—which have security implications when widespread—are external ones.

“Deaths of despair”—premature deaths due to drug overdoses, alcohol poisonings, and suicide—have taken over a million lives in the past decade and precipitated a consistent decline in our national average life expectancy in 2015. Not coincidentally, these deaths are disproportionately concentrated in the very same places in the country where misinformation is most rampant. Not only do many of those places display the challenges noted above, but they also have a high concentration of prime-age labor force drop out, poor health indicators, and high rates of despair and opioid addiction.

We have all too many communities—and individuals within them—that are living in such a deep state of despair, as demonstrated by our mortality figures. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and beginning around 2005, over 70,000 people died of such deaths each year. In 2021, due to the mental health shocks related to the pandemic as well as to the rise in prevalence of the lethal opioid derivative, fentanyl, approximately 120,000 Americans died of overdose alone. The suicide rate—remarkably—remained the roughly the same in 2020-21 as in 2019. Yet we do not know how many of those overdose deaths were intentional (estimates of intentional overdose deaths range from 15-60%). The U.S., while one of the wealthiest countries in the world and home to some of the most important medical innovations, has a crisis of despair-related death on a scale large enough to reduce our average life expectancy.

What is much less known and much less often discussed is the linkages that exist between despair and the misinformation that is plaguing our democracy, civil society, and ability to effectively address the COVID pandemic (and others in the future). New research by neurologists that finds clear linkages between despair and vulnerability to misinformation and the related increase in right-wing radicalization. The confluence of online and physical organizing—including social media usage—enhances that spread. Factors that underpin despair can make people more susceptible to extremist ideologies and create entire geographies that are prone to radicalization and violence. Poverty, unemployment, income inequality, and education levels are all relevant factors.

"Having meaning and purpose in life provides anchors that are not only key to life satisfaction and hope but that makes it far less likely that individuals will fall for false promises or outright lies."

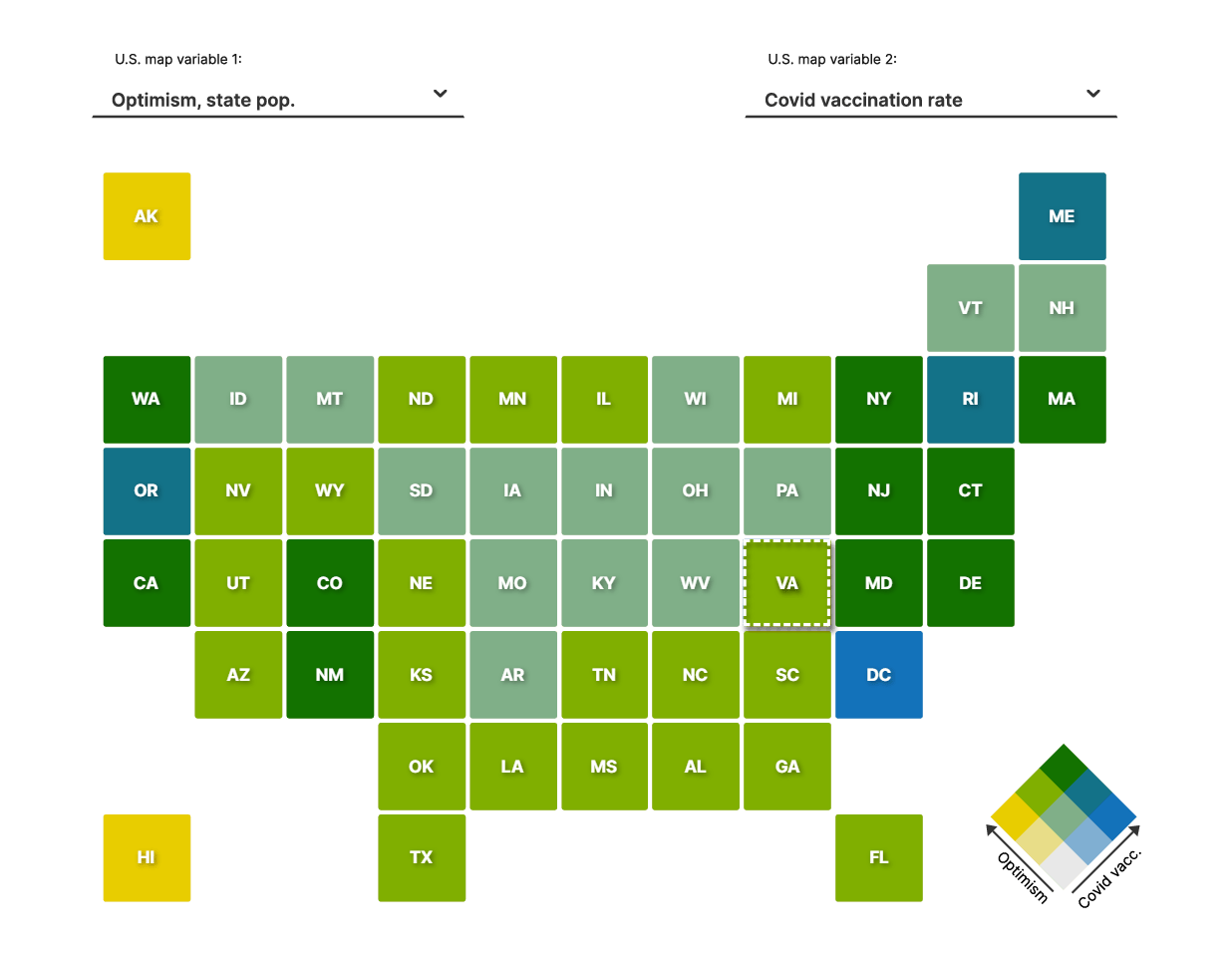

Social identity and psychology, neurocognitive deficits, and dehumanization (as in many work environments) are internal factors that can activate radicalization and violent action. External factors include physical environment, perceived grievances, traumatic life experiences, and social media interactions (including both real and fake actors). There may be structural reasons that both explain the vulnerabilities of some areas to misinformation and clarify how misinformation relates to despair. It is much easier for misinformation to spread in places with low levels of education and a shortage of advanced cognitive skills. These same places also often lack access to health care (particularly mental health care) and do not have trustworthy sources of local news. Skepticism about the value of education, meanwhile, which in part results from despair, is a key factor in the erosion of belief in science. These factors result in a weak base upon which to challenge fake news and rumors, and they all too quickly become “the truth.” It is not a coincidence that low COVID vaccination rates are concentrated in such places. So are despair-related deaths. Increasingly, despair is considered a national security issue as well as a health crisis.

In contrast, people who are hopeful about their futures, which includes believing that they can make them better by investing in them, are much less likely to believe misinformation. Having meaning and purpose in life provides anchors that are not only key to life satisfaction and hope but that makes it far less likely that individuals will fall for false promises or outright lies. Hope is an important part of the equation precisely because it has agentic properties based on the belief that internal forces are in control of individual lives.

More difficult than diagnosing the problem is, as always, finding viable solutions. As a first step, we have built an interactive which highlights the places and populations that are most vulnerable to despair and misinformation. The interactive presents county level information on despair, access to credible local news, cognitive skill levels for high school graduates, COVID vaccination rates, and access to higher education opportunities. It is our hope that this tool can help both academics and local and state level policymakers identify vulnerable places and populations and develop policies to aid them.

Solutions must combine usual policy interventions in the education arena, support for local news provision, and access to credible science and health information. Further, they must seek to overcome the more general problems by seeking to incorporate communities in proposed solutions and increasing community-level wellbeing through better health care, including mental health. Despair at the individual level is often linked to community-wide despair, the analogue to high levels of individual happiness having positive spillover effects on others in the same neighborhood or network

We are at a dangerous point in our democratic history and have a very fragmented civil society. There are myriad of reasons and many possible solutions. Yet we cannot solve these problems if a significant proportion of our society is mired in a crisis of despair in which “many are ambivalent about whether they live or die.” Addressing the dangerous and destructive proliferation of misinformation in precisely those places that are most vulnerable to despair is not easy, but not doing so risks even more damage to our civil society, individual and community-level health, and the ability of our young people to live purposeful and meaningful lives in the future.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors thank the Lumina Foundation for supporting this research.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Despair underlies our misinformation crisis: Introducing an interactive tool

July 13, 2023