Affirmative action policies in college admissions are currently occupying the attention of the U.S. Supreme Court. These policies typically treat black (or other less advantaged) applicants differently, perhaps by granting admission with a lower SAT score. One of the arguments against affirmative action is “mismatch” theory, invoked by Justice Scalia’s recent oral arguments: “There are those who contend that it does not benefit African-Americans to get them into the University of Texas where they do not do well,” he said, as opposed to “a slower-track school where they do well.”

In fact, the evidence for mismatch points to very weak, if any effects, which are in any case dwarfed by the large positive effects of attending a more selective college.

Blacks are more likely to graduate at more selective colleges

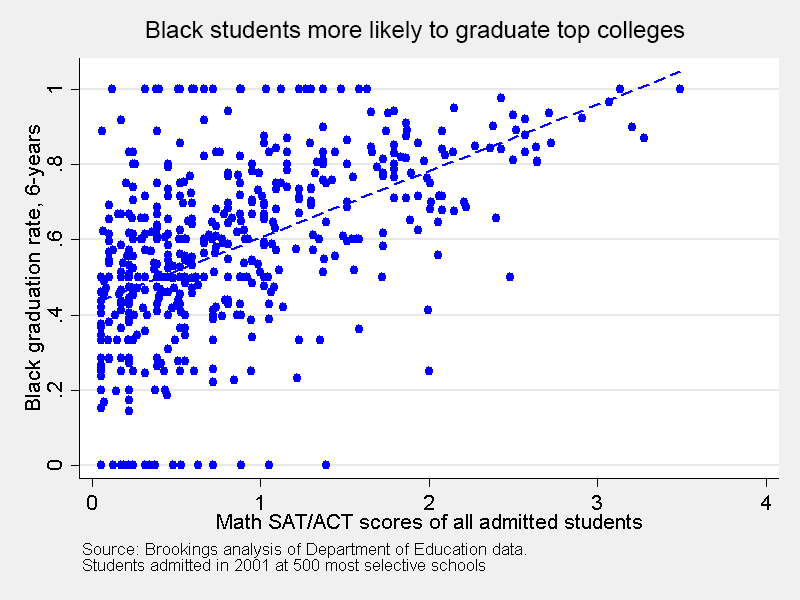

Black graduation rates are consistently higher in more selective colleges:

For students entering the 500 most selective four-year colleges and universities in 2001, the correlation between the black graduation rate and standardized SAT/ACT scores is 0.59. More selective colleges have much higher black graduation rates.

Comparing students with similar test scores, black students at the most selective schools are more likely to graduate and earn STEM credits than their peers at less selective schools, with no difference in grades, according to data from the Department of Education.

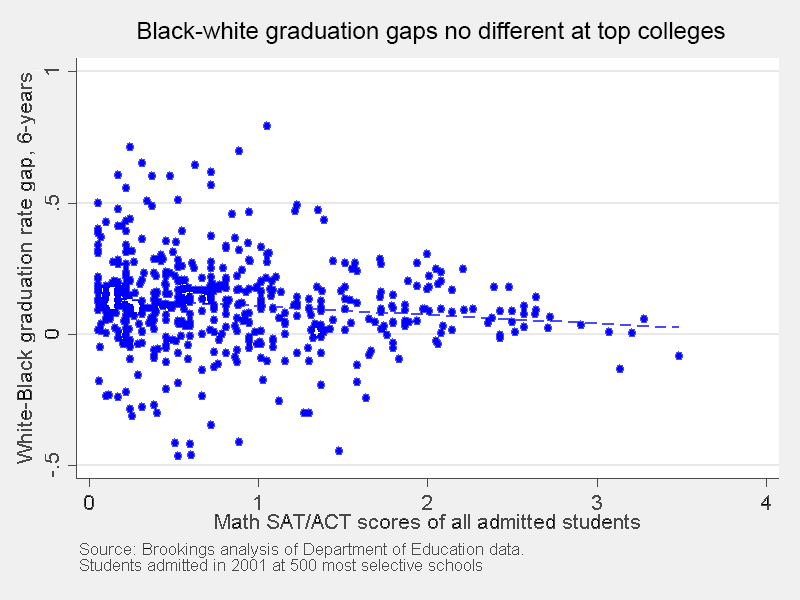

The black-white gap in graduation does not increase with selectivity

Another way to test for mismatch is to compare black and white outcomes at the same school. If black students are being mismatched into top colleges, there should be a larger white-black gap in graduation rates at selective colleges. That is not the case. There is in fact a negative and insignificant relationship between graduation rate gaps and selectivity:

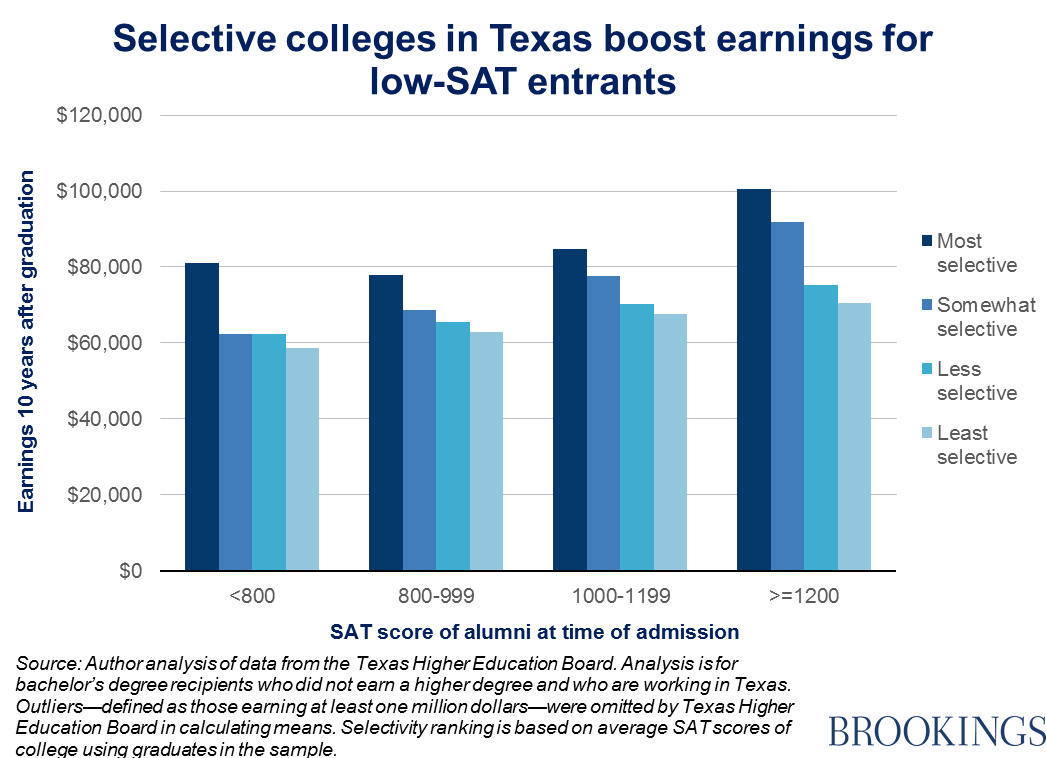

Students with low SAT scores earn big salaries after graduating from top colleges

What about earnings after college? If students with lower SAT scores are mismatched at top colleges, this is likely to show up in post-graduate labor market outcomes. But data from the Texas Higher Education Board suggests that students with low scores do very well after graduating from selective colleges. Even students with extremely low SAT scores at selective colleges out-earn high-SAT students from the least selective colleges:

To put this in perspective, students who scored in the lowest SAT category (less than 800) but graduated from Texas A&M’s main campus earned $86,000 ten years after graduation. By comparison, low-SAT graduates from UT Brownsville earned just $52,000.

Importantly, earnings gaps between high and low scoring students at the most selective colleges are no larger than the gaps at moderately selective colleges, casting further doubt on the idea of mismatch.

Selectivity does not equal quality, however—for any race

Of course selectivity is not synonymous with quality. Many moderately-selective colleges have better teachers and/or more robust student supports that have proven extremely effective in boosting graduation rates overall and in STEM fields. Many less advantaged students—of all races—may benefit from attending these schools, and we certainly need better information about college quality. But there is no compelling evidence to suggest that affirmative action is damaging prospects for the average black student admitted into selective schools. Quite the opposite.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Dear Justice Scalia, black students do very well at top colleges

December 16, 2015