In recent years, an explosion of non-degree credentials (NDCs)—badges, certificates, certifications, and microcredentials—has swept the labor market. NDCs are structured recognitions of skills or knowledge that are typically shorter, cheaper, and more targeted than traditional degrees. There are now more than 1.5 million unique NDCs nationwide. Just in the past year, the number of NDCs listed on U.S. workers’ resumes increased by nearly 35%.

This explosion reflects changes to how skills are acquired, signaled, and rewarded in the labor market. Technological change, especially generative AI, is making job skills obsolete at a faster pace, pushing workers to augment their skills throughout their careers in flexible, targeted ways. At the same time, as job security weakens, occupations appear and disappear more quickly, and career ladders are less clearly defined, workers increasingly seek to signal concrete, job-relevant skills to employers in pursuit of economic mobility. Traditional four-year degrees, meanwhile, have often been slow to adapt to these shifting demands and provide limited visibility into specific competencies.

Against this backdrop, workers across career stages, from early- to late-career, are turning to NDCs to complement formal education, validate their skills, and navigate a labor market where hiring systems struggle to infer capabilities from work experience alone.

For companies, the proliferation of NDCs promises a flexible, skills-first future responsive to their needs. But for workers, the glut of NDCs presents a chaotic gamble. In a market that is crowded, opaque, and largely unregulated, workers often can’t tell the difference between a credential that actually pays off and one that merely clutters their resume or wastes their time and money.

This question has become urgent as federal dollars raise the stakes. The 2025 Workforce Pell Grant expansion extends federal aid to short-term credential programs lasting as little as eight weeks—a policy that could channel billions toward NDCs. Crucially, it grants states and governors discretion over which NDC programs qualify for Pell eligibility.

That discretion creates both risk and opportunity. Without strong accountability, public funds could flood low-value programs and cannibalize degree pathways. With the right guardrails, this is an opportunity to drive accountability. Doing so requires clear standards, robust data infrastructure, and thoughtful methods for NDC assessment.

New research from the Workforce of the Future initiative offers timely guidance. The report (Levy Yeyati, Seyal, and Henn 2025) uses 156.5 million U.S. resumes to study how NDCs relate to wages, education, experience, and occupations. Three core findings stand out, each with direct implications for workers navigating the credential market and for states deciding how to allocate public funding.

What the evidence shows

1. Relevance drives return

Not all credentials create value. Wage returns depend almost entirely on whether an NDC is relevant to a worker’s occupation.

Our research introduces a measure of “job relevance” based on how concentrated a credential is within a given occupation. JavaScript certifications among software developers or project management certifications among management analysts are both highly job-relevant. Credentials that are broadly distributed across unrelated jobs are not.

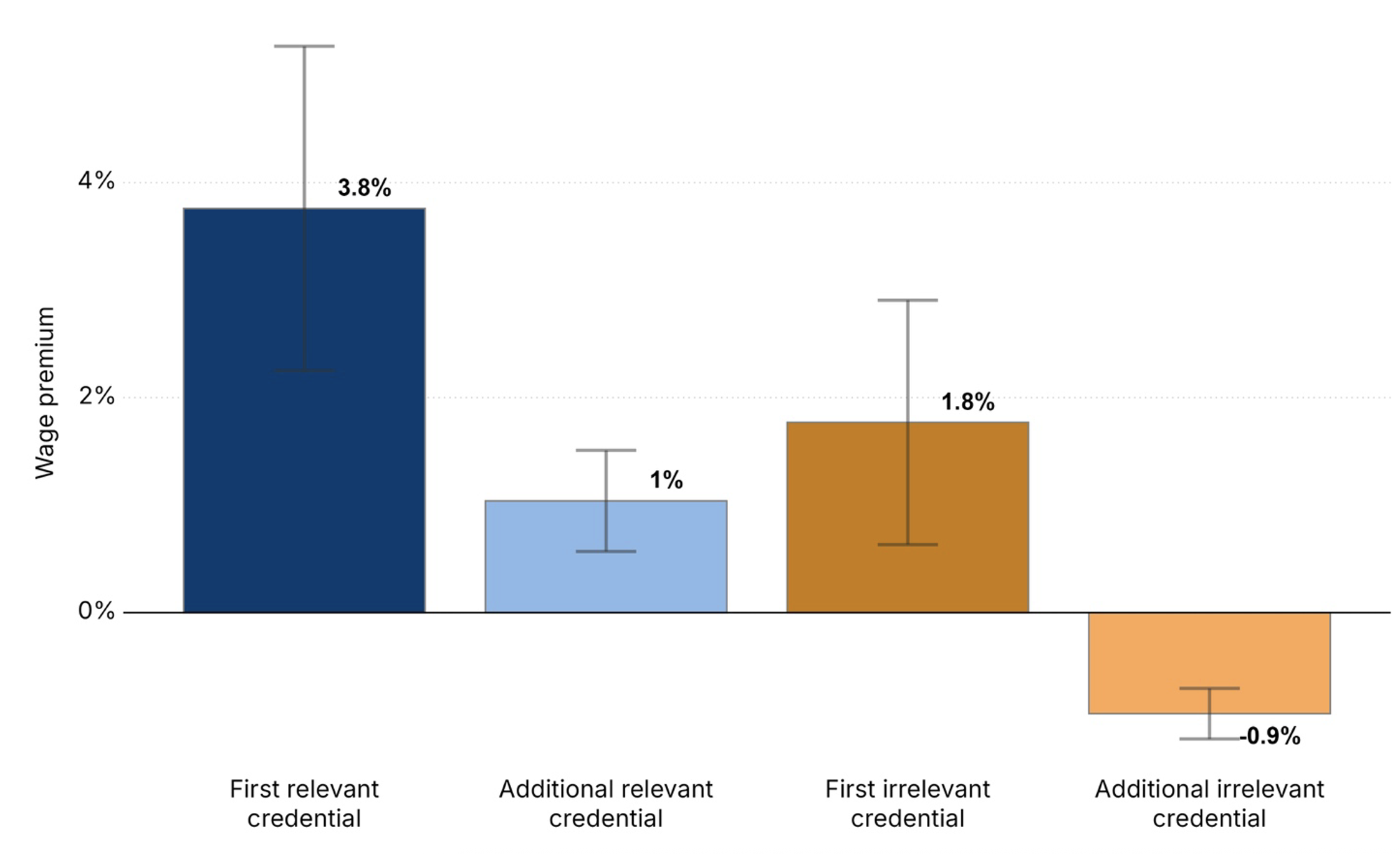

The difference is stark. A worker’s first job‑relevant NDC is associated with a 3.8% wage premium—more than double the 1.8% premium for a first job‑irrelevant NDC. Accumulation only pays off when credentials are relevant: Each additional job-relevant NDC adds another 1.0% to wages. Stacking irrelevant badges yields zero marginal return.

Figure 1. A worker’s first job-relevant NDC is associated with a wage premium twice that of a job-irrelevant NDC

Source: Brookings analysis of Revelio Labs data.

2. Credential type matters

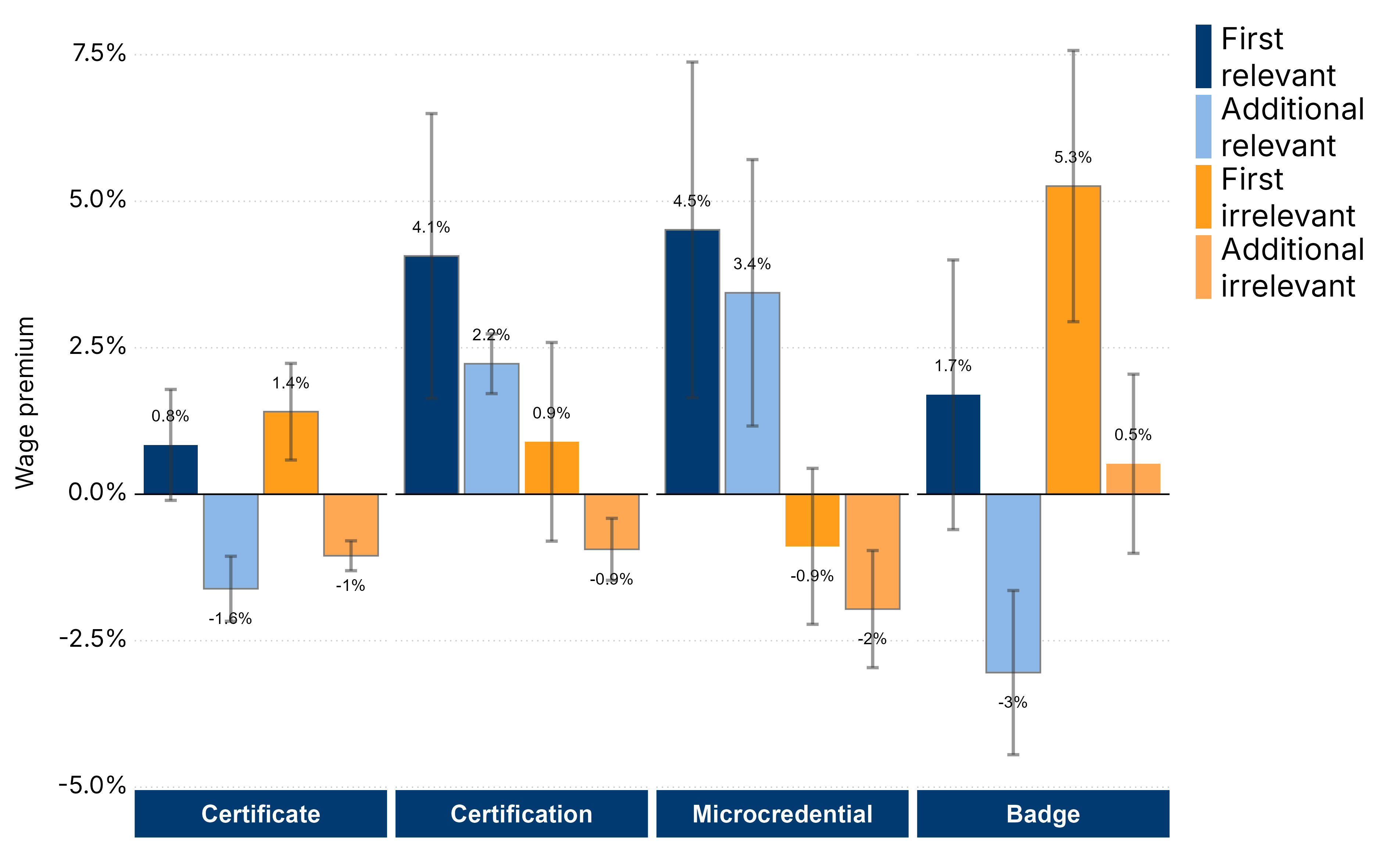

NDCs are not interchangeable. Certifications, which typically require proctored exams, third-party validation and renewal, show strong positive returns, but only when job-relevant. Their accumulation is rewarded, consistent with genuine skill development. Badges and certificates behave differently. They tend to generate a one-time wage bump from initial possession, regardless of relevance, but additional badges or certificates add little to no value. Their returns look more like signaling than skill accumulation.

Whether the salient value of certifications stems from the rigor of assessment, their renewal requirements, or employer recognition remains an important question for future research.

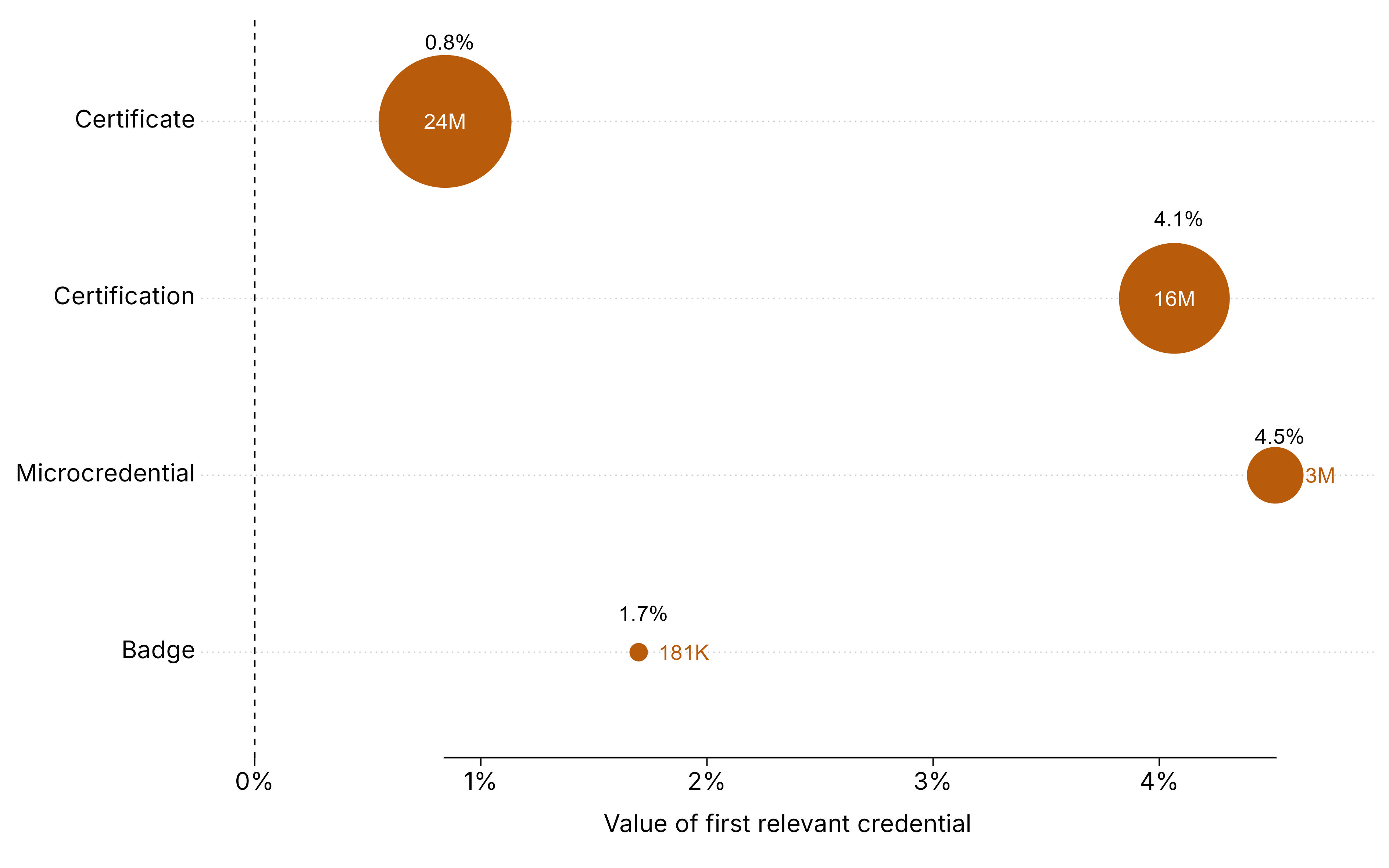

Figure 2. Returns to NDCs range significantly. Certifications are widely held and show strong returns

Note: Certificates: Awarded for completing a program at a college, training provider, or bootcamp (e.g., project management certificate, medical assisting certificate). Certifications: Industry-recognized credentials requiring exams, periodic renewal, and potential revocation (e.g., Certified Public Accountant, CompTIA Security+). Badges and microcredentials: Often digital, modular recognitions of specific skills that can be stacked into larger qualifications. Source: Brookings analysis of Revelio Labs data.

Figure 3. Certifications and microcredentials show returns to possession and accumulation, only when they are job-relevant

Source: Brookings analysis of Revelio Labs data.

3. NDCs matter most for non-college and early‑career workers

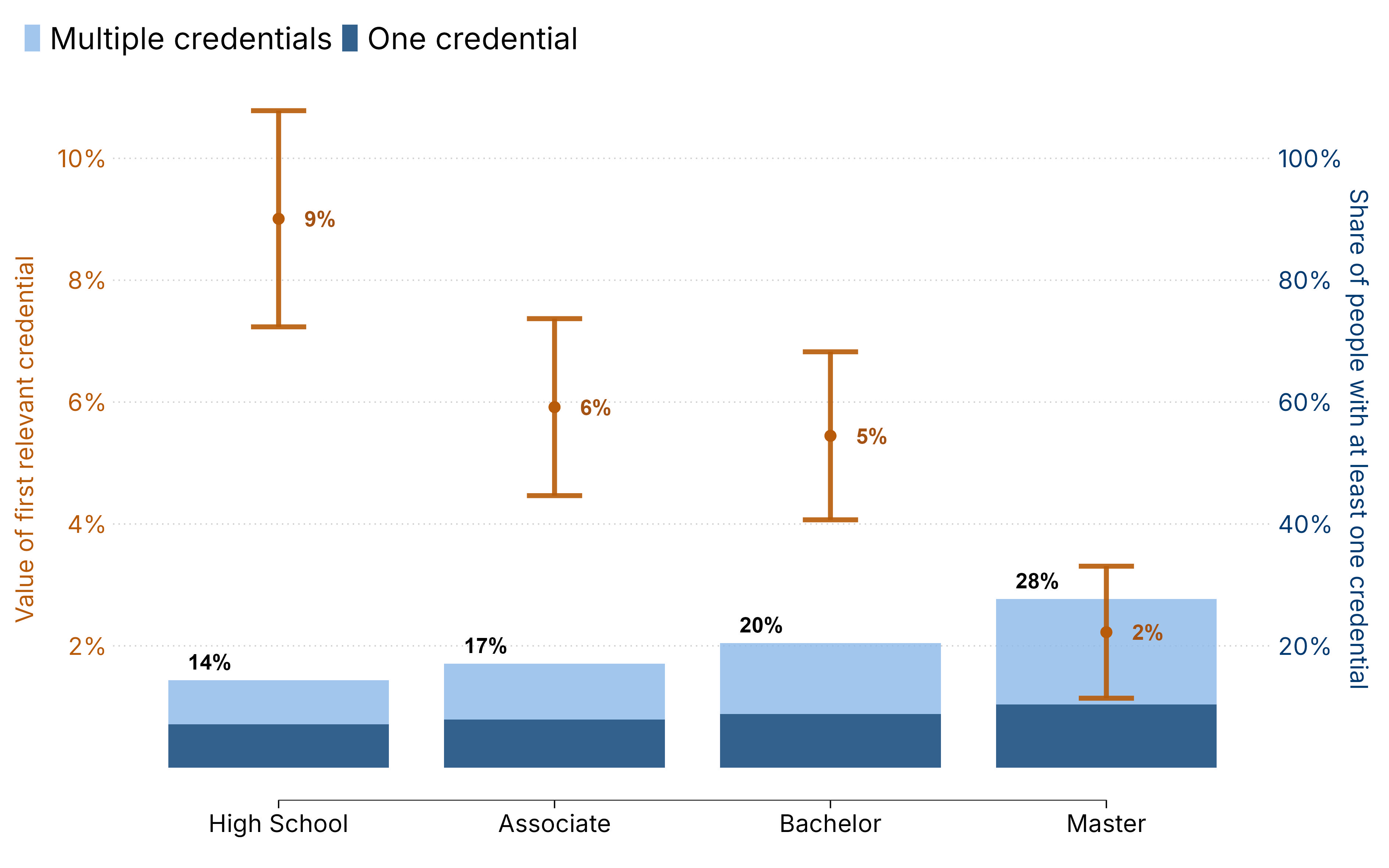

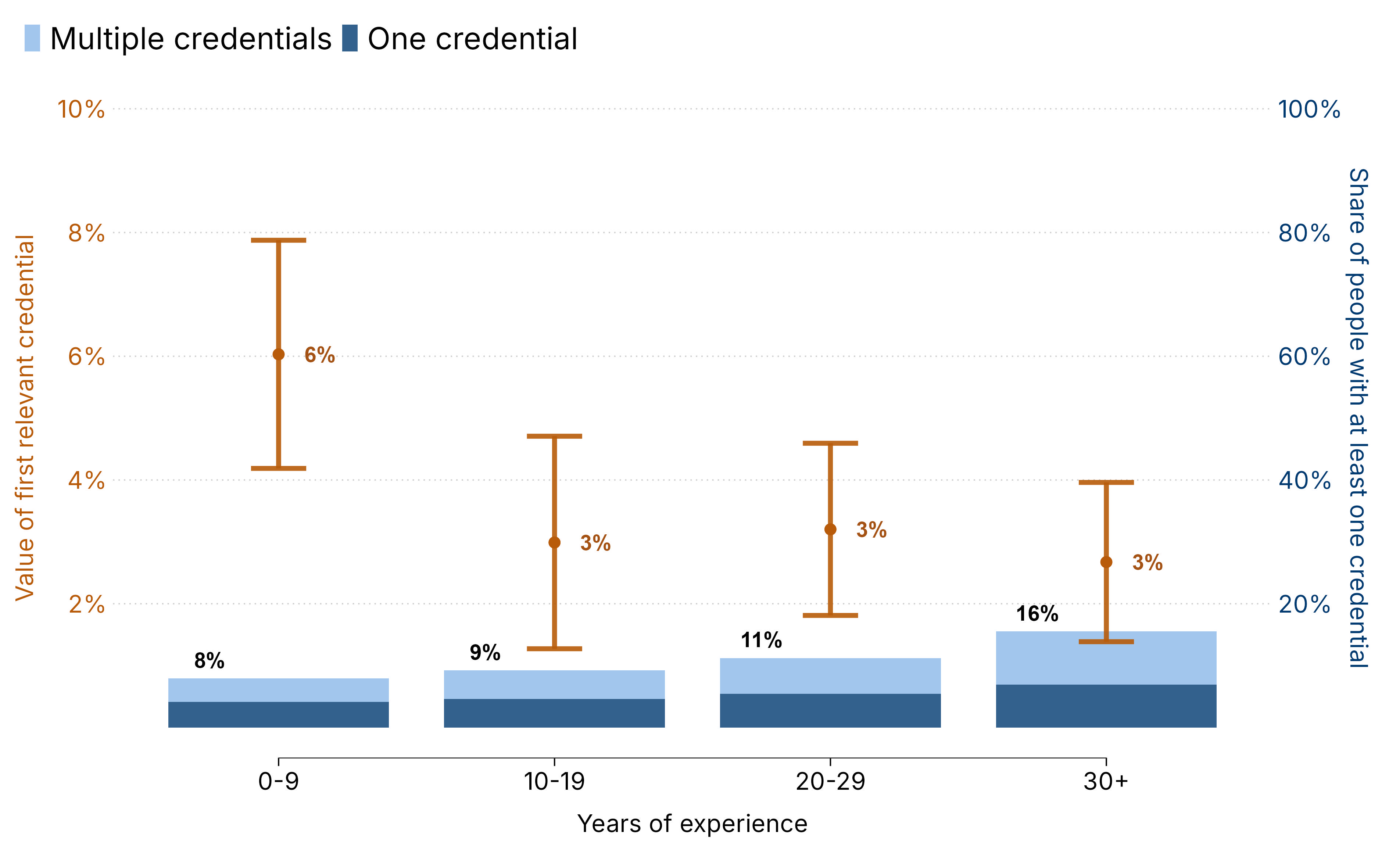

For workers without a bachelor’s degree, a first job‑relevant NDC is associated with a 6.8% wage premium, nearly double the return for college graduates. Early‑career workers see similarly large gains: Roughly a 6% wage premium and more than 2% per additional relevant NDC. For experienced workers, accumulation returns are close to zero.

Despite these higher returns, non-college and early-career workers earn NDCs less often than college-educated and experienced workers—underscoring persistent access and information barriers.

Figure 4. Workers with less formal education see the largest premiums from NDCs

Source: Brookings analysis of Revelio Labs data.

Figure 5. Early-career workers see the largest premiums from NDCs

Source: Brookings analysis of Revelio Labs data.

Taken together, these patterns suggest a simple story. Earning an NDC can help a worker stand out, especially early in their career. But the labor market rewards additional credentials only when they build job‑specific skills that employers recognize and value.

The policy moment: Turning evidence into accountability

These findings come at a critical moment for policy. Generative AI is accelerating skill obsolescence, and the Workforce Pell Grants program is poised to inject large sums of public money into short-term training.

With these funds, accountability becomes even more important. To its credit, Workforce Pell already includes important guardrails: Eligible programs must align with high-demand occupations, place at least 70% of graduates into jobs within 180 days, and demonstrate that graduates’ earnings exceed tuition and fees within one year. Meeting these requirements and helping workers distinguish NDCs that genuinely build skills will demand stronger data systems and clearer standards than most states currently have.

There are several practical steps states can take now:

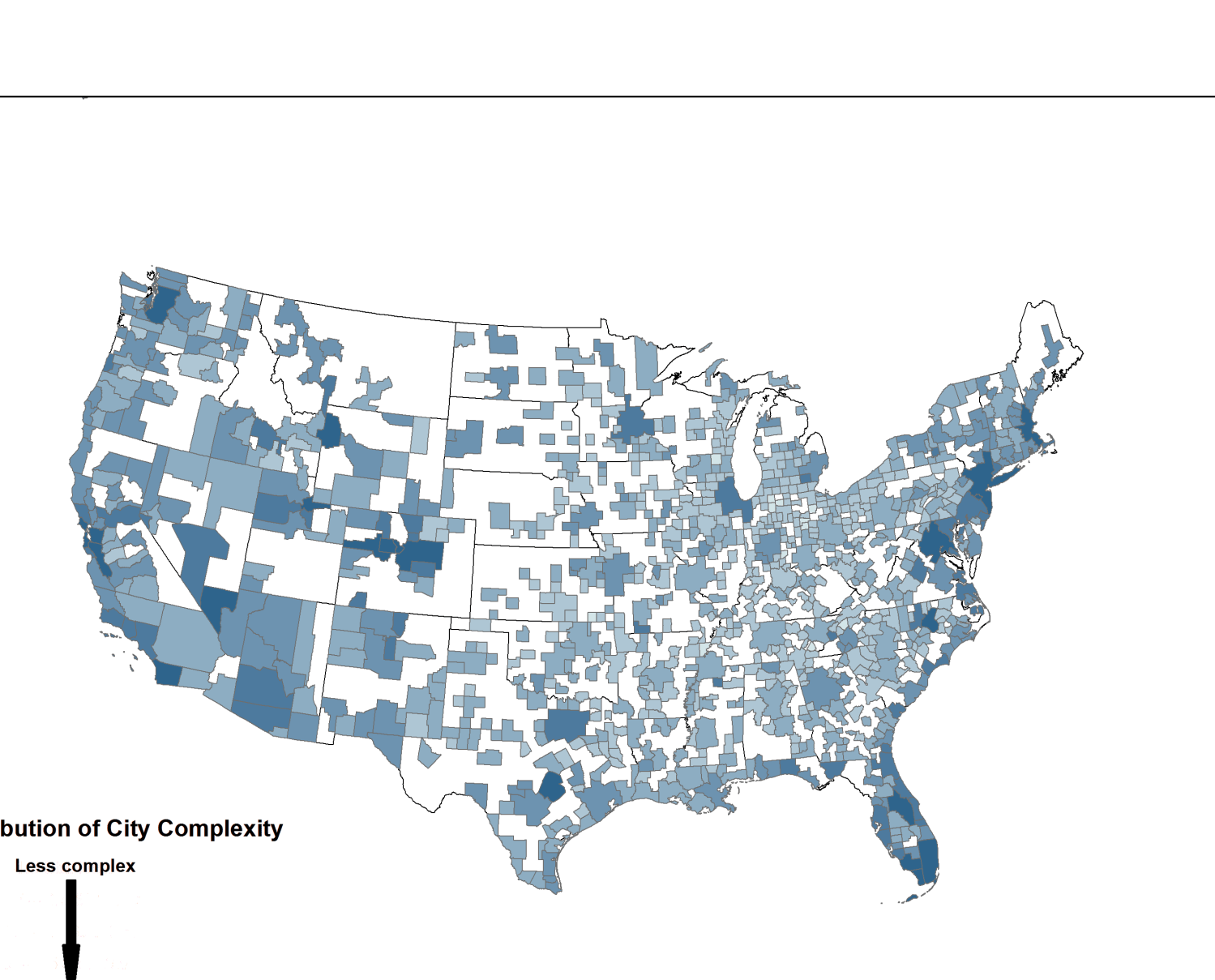

Build transparency around job relevance. Our findings show that job relevance is central to value; workers need to see whether people who earn an NDC actually land in the jobs it claims to prepare them for. States should link credential records to workforce data and publish outcomes such as employment rates, typical wages, industry, and occupation. But to do so, they need to improve their data collection and systems, either by enhancing their UI data collection or by partnering with payroll providers to incorporate timely data. Building better data systems is an arduous process, but they are necessary to assess job relevance and NDC value.

Standardize and publish credential metadata. NDC providers should be on the hook to collect and share data on what skills are taught, how they are assessed, their program cost and duration, and which occupations they target. Building on efforts by Credential Engine and regional partners, states should require providers receiving public funds to publish information with a standardized taxonomy.

Tie public dollars to evidence of value beyond Pell requirements. Workforce Pell’s requirements create a baseline for how to define value. States may find they want to further encourage an NDC market that accelerates their specific economic development goals. For example, rural areas may find a greater need for licensed nurse practitioners, while urban areas may have a growing demand for data scientists. States can leverage other funds such as WIOA training contracts, last‑dollar scholarships, or state grants to further push providers toward rigorous, employer-validated credentials responsive to more localized needs.

North Carolina’s Workforce Credentials Initiative offers an example of rewarding value. The state designates credentials as eligible if data demonstrate they lead to employment in high-growth fields paying family-sustaining wages—and only those credentials qualify for state scholarships.

An opportunity for course correction

The NDC marketplace has exploded, but accountability has not kept pace. Workers shoulder much of the risk, navigating an opaque market with little guidance. That needs to change, especially as public dollars surge into short-term programs. With accountability, NDCs could democratize access to skill development, offering faster and more affordable routes to good jobs, particularly for workers left out of traditional higher education.

The Workforce Pell expansion gives states and the federal government leverage to unlock economic mobility for millions of workers. But policymakers must use that leverage wisely and steer dollars toward credentials with demonstrated labor-market value and transparent outcomes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The credential boom is here, but which ones actually help workers?

February 3, 2026