Introduction

It is commonplace today to assert that American politics and governance are dysfunctional. In many respects, the received wisdom is correct. We survived the most severe financial crisis and economic downturn since the 1930s without falling into another Great Depression, but the country still faces enormous economic challenges. These include reducing near double-digit unemployment, stabilizing a collapsed housing market, restoring a healthy and sustainable rate of economic growth whose dividends are shared widely among Americans, making investments in education, scientific research, clean energy, and infrastructure that give us a chance to prosper in the new economy, strengthening the global financial system, and dealing responsibly with huge budget deficits and debt accumulation that threaten our solvency in the intermediate and long run.

These times call for clear thinking, constructive engagement among policymakers, and decisive public action. Yet such a response by our political system seems, at best, a distant dream. A permanent campaign between the parties puts a premium on strategic partisan interests and relegates serious problem solving to a distinctly secondary priority. Banal ideological nostrums, focus-group-tested talking points, and patently false and often offensive assertions pollute congressional debate and the wider public dialogue. Pledges (for example, the Americans for Tax Reform “no new taxes” statement signed by almost every Republican serving in Congress) and non-negotiable demands by activists and legislators render compromise exceedingly difficult if not impossible. Critical tasks of a responsible and competent government—filling high-level executive and judicial positions, passing routine appropriations and reauthorizations, raising the debt ceiling as necessary—are held hostage to the whims of individual senators or calculations of partisan advantage.

Perhaps we should take heart that the pathologies of contemporary American politics—ideological polarization, extreme partisanship, the permanent campaign, the problem of campaign funding, the rise of new media, the devaluation of compromise, the demise of regular order in Congress—have not rendered policymaking on critical issues completely ineffectual. Large budget deficits in the 1980s turned into surpluses at the end of the 1990s in large part because of comprehensive budget agreements between presidents and Congress in 1990 and 1993. In 2008 and 2009, Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama and the Federal Reserve took critical steps in coordination with the G20 to stabilize the financial system and stimulate the economy, which together contained the global financial crises and averted an even more devastating collapse of the economy. As part of that effort, President Obama won passage of a large and necessary stimulus plan, even if the amounts involved were not large enough to restore robust economic growth. He also pushed a landmark health reform through Congress in 2010 as well as a reform of the financial regulatory system. A lame duck session at the end of the 111th Congress produced bipartisan agreements on ratifying an arms treaty with Russia, ending the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy on gays and lesbians in the military, and additional measures to stimulate the economy.

Yet those considerable achievements provided little respite from protracted political wars and policy challenges. The budget surpluses at the turn of the century soon returned to deficit with the adoption of policies that cut taxes and increased spending; those deficits then ballooned during the recession. The public quickly turned on the economic crisis management of 2008 and 2009, perhaps unsurprisingly given the halting and painful recovery and the perception that those most responsible for the financial crisis benefited most from steps taken to contain it. Republicans almost unanimously denied any benefit from Keynesian initiatives to shorten and ameliorate the ill effects of the recession and unabashedly insisted that “job-killing government spending” was the primary source of our economic difficulties.

The election of a Republican majority in the House in 2010 led to aggressive efforts to disable the implementation of the new health insurance and financial reform legislation and to enact immediate, substantial cuts in domestic discretionary spending. After an agreement was reached halfway into the FY 2011 budget year, Congress was mostly MIA, biding its time while a handful of negotiators convened by Vice President Joe Biden struggled to reach a deficit reduction agreement sufficient to garner the votes in the House and Senate needed to raise the debt ceiling and avoid a potentially catastrophic default.

We write this paper not simply to repeat or update widespread criticism of American politics and governance. Our intention instead is to supplement ongoing work at Brookings explaining the causes of the dysfunction and assessing the promise of various electoral reforms and institutional innovations in ameliorating it.[1] Specifically, we consider here whether the nature and quality of political leadership is important in identifying the sources of our governance problems and in developing strategies to work around them.

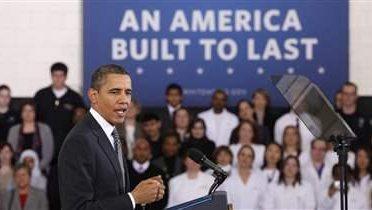

Public commentary on the failures of American politics is replete with critiques of the personal qualities and behavior of leaders in all three branches of government. Presidents understandably garner the lion’s share of this attention. President Obama is faulted, to take but a few examples, for not focusing like a laser on the economy at the outset of his administration, deferring too much to the Congress on the substance of major legislative initiatives, failing to craft a convincing narrative to help the public understand the true nature of the problems we confront and his proposed path to recovery, and not taking a more forceful and visible role in producing the post-partisan government on which he campaigned.

Congressional leaders routinely disappoint those looking to the first branch to deal forthrightly with the country’s most daunting challenges. As Speaker, Nancy Pelosi was criticized for running the House in a highly partisan and centralized fashion, one that froze out the minority and skewed policy to the left. Her successor, John Boehner, has loosened the reins a bit but often is portrayed as hapless in the face of an ideologically extreme party caucus. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has been pilloried for indiscrete public statements and an inability to make the Senate work. His Republican counterpart, Mitch McConnell, has had no compunction in framing a strategy of uncompromising opposition to President Obama’s legislative initiatives and in publicly stating that his highest priority in the Senate is to ensure that Obama is a one-term president. Critics also bemoan the absence of strong and effective committee leaders and the legendary whales that populated past Congresses.

Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, while presiding in the political institution most trusted by the American public, is not immune from a similar sense of disappointment by those longing for constructive and effective governance. Critics allege that Roberts, contrary to the sentiments and intentions he expressed during his confirmation hearing, has reinforced and exacerbated the ideological divide on the Court and pursued an aggressively conservative judicial activism.

James MacGregor Burns, in his classic book on leadership, distinguishes two types.[2] Transactional leadership, based on exchanges between leaders and followers, is characteristic of leader-follower relationships in groups, legislatures, and parties. Its primary mode of operation is bargaining to produce a discrete outcome. Transformational leadership, on the other hand, involves a fusing of purpose among previously disconnected or conflicting individuals that produces a mutual and continuing pursuit of a higher purpose. Burns cites Gandhi as the best modern example of a transformational leader, in this case one “who aroused and elevated the hopes and demands of millions of Indians and whose life and personality were enhanced in the process.”[3]

The quest for better, more effective leadership in American politics today sometimes focuses on more skillful transactional leadership. Often, however, it imagines the possibilities of visionary, courageous, inspiring leadership at all levels of government that can transform the bitter partisan and ideological divides and render our public life more productive and satisfying. These two models will inform our analysis of congressional leadership in the recent past and our assessment of its future.

[1] David W. Brady and Pietro S. Nivola, eds., Red and Blue Nation? Volume 1 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press and Hoover Institution, 2006); David W. Brady and Pietro S. Nivola, eds., Red and Blue Nation? Volume II (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press and Hoover Institution, 2008).

[2] James M. Burns, Leadership (New York: Harper & Row, 1978).

[3] Burns, Leadership, p. 20.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).