This is the introduction and executive summary of a new Brookings report—to be released on March 28—on addressing the Iranian missile challenge.

For decades, the United States has sought to constrain Iran’s missile program, both because it poses a conventional military threat to regional stability and because it can provide a delivery capability for nuclear weapons should Iran acquire them. But despite the efforts of the United States and others to impede Iranian procurement of missile-related materials, equipment, and technology and a succession of U.N. Security Council (UNSC) restrictions imposed largely to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons delivery systems, Iran has managed to acquire the largest and most diverse missile force in the Middle East.

The Iranian missile threat

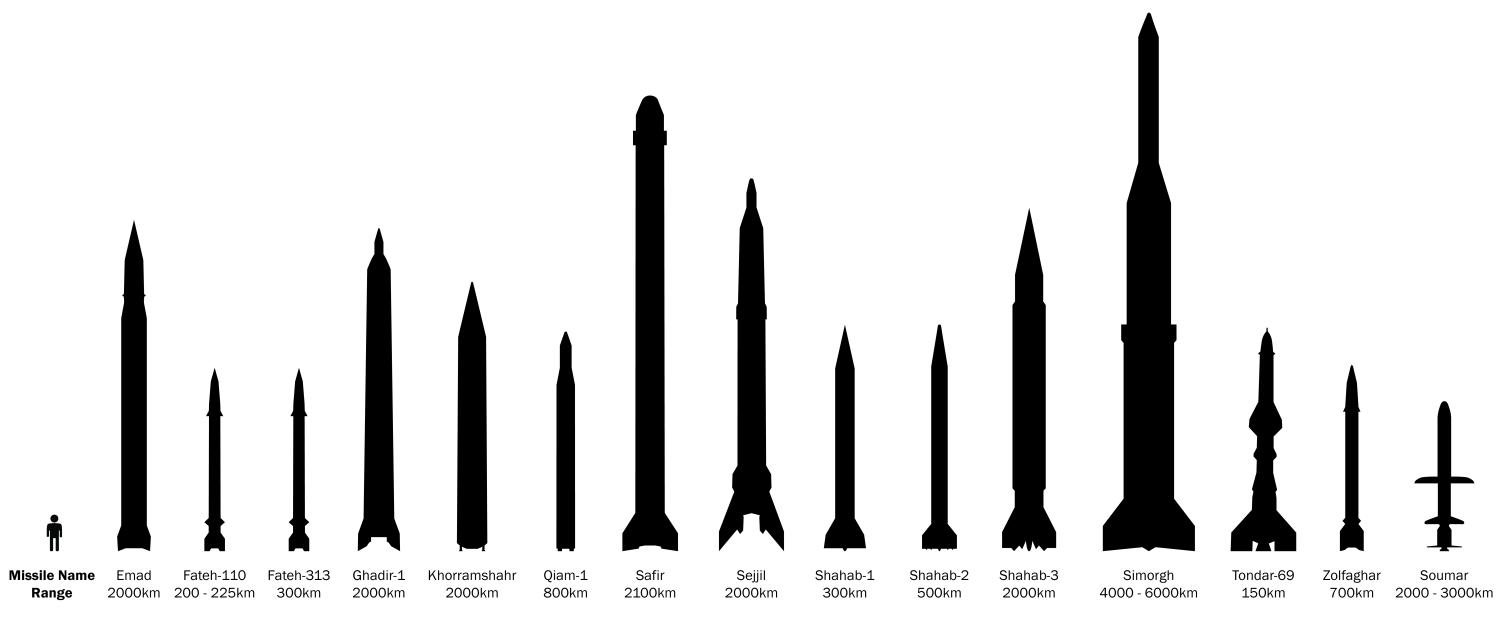

Relying initially on missiles, components, and technology purchased mainly from North Korea and China, but increasingly making advances through indigenous efforts, Iran maintains a force of hundreds of liquid- and solid-propellant short- and medium-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs and MRBMs), now being augmented by land-attack cruise missiles. Although claiming to limit itself to ballistic missiles with a 2000 km range by order of the supreme leader and not yet launching ballistic missiles above that range, Iran pursues at least four paths that it could use to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of reaching the United States, including the development of space-launch vehicles (SLVs) based on technologies directly applicable to long-range ballistic missiles. While placing priority on indigenous development, Iran remains dependent on importing key components and materials. It is working on more accurate guidance systems to improve the military utility of its missiles and has fielded road-mobile missile launchers to promote their survivability against attack.

The Iranians see their missile force as an integral and indispensable part of their national defense strategy, fulfilling key strike roles traditionally taken by manned aircraft, but beyond the capabilities of an Iranian air force hobbled by many years of sanctions. The missile program serves key Iranian goals: deterring attacks against Iran, providing warfighting capabilities if deterrence fails or Iran decides to initiate hostilities, supporting military capabilities of regional proxies such as Hezbollah and the Houthis, enhancing national pride and regional influence, and providing a nuclear delivery hedge if Iran decides to acquire nuclear weapons. The use of Iranian ballistic missiles is not just theoretical. Iran has fired ballistic missiles against Iraq during the Iraq-Iran war and against various non-state actor adversaries in neighboring states in recent years. Moreover, Iranian proxies have fired Iranian-supplied missiles and rockets at U.S. regional partners Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Iran’s missile program poses a serious threat to the security interests of the United States and its partners, both in the Middle East and beyond. Key U.S. objectives with respect to that program are to deter attacks and intimidation against the United States and its friends, impede quantitative and qualitative improvement in the regional missile capabilities of Iran and its proxies, maintain military capabilities that can degrade the ability of the missile forces of Iran and its proxies to achieve their objectives, and discourage and delay the development of missile capabilities that can reach beyond the region, including to Western Europe and the U.S. homeland.

The Trump administration’s approach

President Trump has cited the absence of missile constraints in the Iran nuclear deal— officially called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—as one of its major flaws and a key reason he decided to withdraw from the agreement. By withdrawing from the JCPOA and re-imposing sanctions against Iran that were suspended under the deal, the administration hopes to place overwhelming pressure on Tehran and compel it to accept a comprehensive “new deal” meeting the 12 highly ambitious requirements outlined by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in May 2018, including the halt of all uranium enrichment, the end of Iranian support to Middle East terrorist groups, and the withdrawal from Syria of all forces under Iranian command.1 On the missile issue, the requirement is that “Iran must end its proliferation of ballistic missiles and halt further launching or development of nuclear-capable missiles.”

While talking about a new comprehensive deal with Iran, administration officials do not seem to be looking to negotiate separate solutions to their various concerns about Iranian behavior, including a separate missile deal. Instead, they appear to be counting on their “maximum pressure campaign” to produce either a fundamental change in Iran’s outlook and policies that would be reflected in an across-the-board capitulation to U.S. demands or, what many observers assume to be their true objective, the collapse of the Iranian regime.

Approach of other countries to Iran’s missile program

The European response. While France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (the E3) have strongly opposed U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and have actively worked to circumvent U.S. sanctions in the interest of persuading Iran to remain in the deal, they generally share U.S. concerns about Iran’s missile program. They have condemned Iranian missile launches as inconsistent with the missile restrictions of UNSC Resolution 2231, opposed Iran’s missile-related assistance to its regional proxies, and encouraged negotiations aimed at placing restraints on Iran’s missile capabilities and exports. But the 28 members of the European Union (EU) do not have a uniform view of the Iran missile threat and the means for dealing with it. While France and the United Kingdom pushed hard for new EU missile sanctions against Iranian entities, the group failed to reach the consensus needed for their adoption.

The Russian response. Russia was a constructive partner in the JCPOA negotiations. But since the conclusion of the JCPOA—and the sharp deterioration in U.S.-Russian relations—the positions of Washington and Moscow on Iran issues have significantly diverged, including on the missile issue. Russia has been Iran’s chief defender in the Security Council, vetoing a British draft resolution condemning Iran for supplying missiles to the Houthis in violation of the UNSC-mandated Yemen arms embargo and maintaining that Iran is respecting in good faith the call in Resolution 2231 to refrain from activities related to ballistic missiles “designed to be capable of delivering nuclear weapons.”

Middle East state responses. Not surprisingly, the countries that are America’s closest Middle East partners, Iran’s major regional adversaries, and the most significant potential targets of Iranian and Iranian-assisted missile attacks—Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—are the strongest opponents of Tehran’s missile program and the missile and rocket capabilities of Tehran’s regional proxies. Unlike the Europeans, their preferred means of addressing missile threats from Iran and its proxies do not include direct negotiations with Iran. Instead, they prefer more coercive policy tools—sanctions, interdictions, and possibly pre-emptive military strikes.

Iran’s opposition to missile constraints

Iran has repeatedly and adamantly rejected Western interest in constraining its missile capabilities. Notwithstanding evidence in the Iranian nuclear archive acquired by Israeli intelligence of an Iranian project to examine the integration of a nuclear payload into a re-entry vehicle for the Shahab-3 medium-range missile, Iranians argue that their missiles are designed exclusively to be armed with conventional munitions. Maintaining that their missile force is an essential part of their legitimate self-defense capabilities, they claim that their missile capabilities are needed to rectify a conventional military imbalance in the region created by the decades-old Western arms embargo against Iran and by the supply of advanced weapons systems by the United States and other Western countries to Iran’s regional rivals. In response to appeals that Iran agree to missile talks, Iranian officials at all levels assert that Iran’s missile capabilities are non-negotiable. They are often proud to publicly announce ballistic missile launches and other advances in indigenous missile development, as well as to acknowledge missile strikes against “terrorist” targets.

On the question of whether Iran will continue to observe a voluntary range limit of 2000 km on its ballistic missiles putatively established by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, Iranians have been ambiguous. On the one hand, they state that they have no need for missiles of longer range because the enemy targets they would need to strike are within 2000 km. On the other hand, they assert that they already have the scientific capability to build missiles of longer ranges, that they could build such missiles if the threat changes, and that they are under no legal obligation not to do so.

Policy tools to address the Iranian missile threat

For several reasons, reducing the Iranian missile threat is a formidable challenge. Iran already possesses extensive missile capabilities and the expertise indigenously to continue advancing those capabilities. It believes it faces major external threats and regards its missile program as a critical means of addressing those threats and of promoting its regional political and security goals. Unlike in the case of its nuclear program, it does not consider itself under any legal obligation to limit its missile capabilities and does not face united international opposition to its missile program; it even receives support from key countries for its stance on missile issues.

Overcoming these obstacles—and promoting U.S. objectives against Iran’s missile program—will require the simultaneous application and creative, rigorous implementation of a broad range of policy tools.

- National and multilateral trade controls (e.g., those of the Missile Technology Control Regime, or MTCR) and case-by-case, ad hoc interdictions (i.e., stopping specifically identified individual transfers of equipment, technology, and funds to and from Iran’s missile program) will play an important role in impeding quantitative and qualitative improvement in the Iranian missile threat. The United States should continue to press key source countries (e.g., China) and transit and transshipment countries (e.g., UAE, Singapore, Malaysia) to strengthen their missile-related trade controls, and it should cooperate and share intelligence with countries in a position to interdict sensitive transactions. But these policy tools are of diminishing marginal utility in the face of the large size of Iran’s force and the increasing sophistication of its indigenous missile production capability.

- This means that there will be an increasing need to rely on military capabilities— the mutually reinforcing set of offensive attrition, missile defenses, and passive defenses—and declaratory policy to deter, defend against, and deny the objectives of Iran’s missile program.

- To deter Iranian missile attacks and limit Iran’s ability to achieve its warfighting objectives, the United States and its regional partners should further develop offensive military capabilities—ranging from cyber operations to kinetic pre-emptive means—to be able to carry out counterforce strikes against Iranian missile forces and production infrastructure, both before and during conflict.

- While ballistic and cruise missile defenses are expensive, imperfect, and can be overwhelmed by Iranian increases in offensive missiles, they can help protect against attacks involving small numbers of missiles, complicate Iranian attack planning against specific targets, and provide U.S. regional partners a measure of confidence to withstand Iranian intimidation and threats. In cooperation with its partners, Washington should seek to enhance defenses against Iranian missiles, both regionally and extra-regionally (including potential future threats to Western Europe and the American homeland).

- Upgrading passive defenses of key regional airbases, ports, command and control facilities, and other critical nodes—through such methods as hardening, concealment, duplication, and preparations for rapid repair—can reduce the vulnerability of protected assets to missile attack and degrade Iran’s ability to meet specific regional military goals.

- Under current U.S. declaratory policy, Iran will be held accountable for any direct or proxy attack that results in injury to U.S. personnel or damage to U.S. government facilities. Washington should consider extending that policy to cover direct Iranian missile attacks on partner countries unrelated to U.S. personnel and facilities and to warn of appropriately strong responses to such Iranian actions as the flight testing or deployment of an ICBM capable of reaching the U.S. homeland or an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) capable of reaching all of Western Europe.

- Sanctions and diplomatic pressure will remain important policy tools to dissuade other countries from assisting Iran’s missile program and to increase the prospects that Iran can be persuaded at some point to limit aspects of its missile program.

- Given the low probability of further UNSC sanctions against Iran, the sanctions most likely to impact Iran’s missile capabilities would be U.S. sanctions on third-party entities doing business with Iran’s missile program. For this to be effective, Washington must be prepared to elevate the priority of constraining Iran’s missile program—and potentially to incur costs—in bilateral relationships with countries having jurisdiction over such entities, such as China (and Hong Kong), Malaysia, Russia, Singapore, Turkey, and the UAE.

- The United States and like-minded countries should engage in active public and private diplomatic efforts to underscore the threats posed by Iran’s missile force, to warn countries like Russia and China of the implications for them of a growing Iranian missile force (including possible sanctions against their entities and a build-up of U.S. and partner missile defenses), to urge countries with influence in Tehran to press for missile restraint, and to improve receptivity to Iran-related counterproliferation and trade control efforts by the United States.

Diplomacy with Iran to promote missile restraint

The final policy tool for countering the missile threat from Iran and its proxies is direct diplomacy with Iran. Although this may be the tool many governments think of first when considering the missile issue, Iran’s military reliance on missiles, its related refusal to engage in negotiations on its missile capabilities, and the confrontational state of U.S.- Iranian relations render negotiated restraint unlikely to be realistic anytime soon.

The other policy tools described above will therefore be the most promising ways of addressing the Iranian missile threat in the near term. If effective, they can complicate, slow, and impede Iran’s missile activities; deter Iran from using missiles; and degrade the ability of Iran’s missile force to achieve its military and political objectives. But these other tools cannot prevent a determined and resourceful country like Iran from pursuing missile activities. Ultimately, it is up to Iran to restrain its missile program.

So diplomacy with Iran should remain part of the overall toolkit, both because circumstances might change in the future to make missile negotiations more promising and because U.S. readiness to negotiate could help build international support for the other measures needed to deal with the Iranian missile threat in the event that diplomacy is not feasible.

Several negotiated restraint options, which could be pursued individually or in combination, are addressed in this report and are evaluated in terms of their likely effectiveness in reducing the threat, their monitorability, and their negotiability (i.e., the likelihood Iran would agree). A number of those analyzed fall short on one or more of these criteria and do not appear promising to pursue for the foreseeable future, including: a ban on development of nuclear-capable missile systems, a ban on launches of all nuclear-capable systems, a ban on new types of missiles, a limit on the number of missile launches, a ban on possessing nuclear-capable missiles, and Middle East regional missile constraints.

This report’s evaluation does, however, suggest that two potential negotiating objectives hold more promise in terms of reducing the Iranian missile threat, monitorability, and negotiability:

- Banning Iranian launches of long-range rockets (e.g., greater than a range of 2000 km), if accompanied by definitions and restrictions to prevent circumvention, could substantially reduce the Iranian missile threat to the U.S. homeland with high monitorability and consistent with Iran’s claimed policy and current practice, but would not affect SRBM and MRBM systems.

- Banning Iranian launches of rockets with multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicle (MIRV) payloads and launches of nuclear-capable rockets from air, sea, and submerged platforms would impede in a highly monitorable way new attributes that would increase the warfighting capability, ability to penetrate missile defenses, and survivability of Iran’s missile force. But it would not reduce the current Iranian missile threat, or increases in that threat, using other payload types and basing modes; this same lack of current impact may mean that Iran would be more willing to accept it.

A third potential negotiating objective might have promise if there is progress in reducing regional tensions or resolving key regional disputes: banning Iranian missile-related exports. This could limit increases in the missile threat from Iran’s proxies, albeit not their current inventories or the direct threat posed by Iran’s own missile force. Tehran presumably would be more willing to negotiate an export ban than limits on its own forces, and an improved regional situation might reduce Tehran’s interest in using missile-related exports to promote its foreign policy objectives. Over time, the fact of continuing violations of an export ban probably would be detected.

Space-launch vehicles. Because SLVs are inherently capable of delivering nuclear weapons, any negotiated limits on long-range missiles should also apply to SLVs. However, if Iran is only prepared to accept meaningful limits on ballistic missiles if SLVs are permitted, the United States would need to decide whether the constraints on ballistic missiles that Tehran is willing to accept, at the negotiating price it is asking, are worth running the risk of allowing Iran to retain SLVs inherently capable of delivering nuclear weapons and serving as a technology testbed and breakout repository for an ICBM program. If the United States decides that permitting Iran to retain SLVs is worth the risk, various collateral constraints have been proposed to limit their weapons delivery potential.

Incentivizing Iranian missile restraint. Iran can be expected to seek compensation for any negotiated missile restraints. But what carrots would be reasonable to provide Iran would depend on the constraints it is willing to accept. If, for example, Tehran is only prepared to reaffirm or codify its existing position—that it does not need missiles that exceed 2000 km—it should expect to receive little in exchange. But if it is prepared to accept more significant limits, such as restrictions on flight tests of long-range missiles or a ban on missile-related exports, it could expect to receive more, such as a relaxation or suspension of U.S. missile-related sanctions.

U.S. missile diplomacy with Iran would presumably be embedded in a broader diplomatic effort to seek modifications of Iranian behavior in several areas of concern, including Tehran’s nuclear program and its destabilizing role in the Middle East. Therefore, the question of incentivizing Iranian missile restraint would have to be considered in the context of the leverage available to promote Iranian restraint across the board—and how to allocate that leverage to achieve various negotiating objectives.

Looking ahead

Iran will continue efforts to improve the accuracy and lethality of its SRBMs and MRBMs and to expand its regional ballistic and land-attack cruise missile forces. Tehran also will continue to pursue several parallel paths to develop IRBMs capable of reaching all of Western Europe and ICBMs capable of reaching the U.S. homeland, at least as a hedge.

There is much the United States can do using the full spectrum of policy tools at its disposal to impede improvements in Iran’s missile force and to mitigate its threat. The United States can help partner countries strengthen their trade and transshipment controls and can cooperate with them to enhance their attrition capabilities, their defenses against ballistic missiles and land-attack cruise missiles, and their passive defenses. Washington can also coordinate closely with partners to increase diplomatic pressure against Iran’s missile program, to raise international awareness of the Iranian missile threat, to remain vigilant against Iranian missile-related procurement efforts, and to complete NATO’s planned defenses against any future Iranian missile attack.

Many of those policy tools would be most effective if the United States had the full cooperation of the international community. In the current contentious international environment, that cooperation will not always be forthcoming. In particular, Russia, China, and other countries that have problematic bilateral relations with the United States and are sympathetic toward Iran may often oppose U.S. efforts. But the United States should continue to press hard on the Iranian missile issue with Russia, China, and other such countries.

While seeking international support for addressing the Iranian missile threat, the United States will also need to act unilaterally—including by further developing and deploying missile defenses, imposing U.S. sanctions when UNSC and other multilateral sanctions are not possible, using public diplomacy to raise awareness of the missile threat from Iran, developing attrition capabilities potentially applicable in Iran, and announcing declaratory policy regarding how the United States may respond to Iranian missile-related provocations.

But the above types of measures can only go so far in impeding and countering the Iranian missile threat. At the end of the day, it is Iran’s choice whether to restrain its missile program. This is why the United States must be prepared, if the opportunity arises, to engage in direct diplomacy with Iran to seek restraint in its missile program.

That said, the near-term outlook for directly engaging Iran and negotiating meaningful missile limitations is poor. The Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign is putting great stress on the Iranian economy, but it is unlikely to force Iran to capitulate to U.S. demands that Tehran considers extreme and unjustified and that it believes are motivated by a desire to undermine the regime. Indeed, far from compelling Iran to rein in its missile capabilities, the administration’s anti-Iran campaign may convince Iran’s leaders that they should strengthen those capabilities against a growing American threat. And if Iran decides to withdraw from the JCPOA and build up its nuclear program, the U.S.-Iranian confrontation could escalate—and conditions for Iranian missile restraint would deteriorate further.

In these circumstances, it is hard to imagine productive engagement with Iran on its missile program in the next two years. Whether a successor U.S. administration will be in a better position to pursue negotiated limitations on Iran’s missile activities will depend on a variety of factors, including whether the current U.S.-Iranian confrontation can be eased and whether talks on other issues, mainly on updating and extending the nuclear deal, can begin.

So, at least for the time being, the United States should focus its efforts to counter the Iranian missile threat on policy tools that do not require direct engagement with Iran or Iranian consent. Many of these efforts are already being pursued to varying degrees, and indeed have been pursued under several previous U.S. administrations. The United States should intensify these efforts, better integrate them, and elevate their priority in dealing with the overall Iranian challenge—and their priority in U.S. bilateral relations with key states. There is still much work the United States can do at present to address the Iranian missile threat.

-

Footnotes

- Mike Pompeo, “After the Deal: A New Iran Strategy,” (speech, Washington, DC, May 21,2018), https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2018/05/282301.htm; Human rights apparently were added subsequently as a 13th condition. See Noah Annan, “Pompeo Adds Human Rights to Twelve Demands for Iran,” Atlantic Council, October 23, 2018. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/pompeoadds-human-rights-to-twelve-demands-for-iran.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).