What’s the secret to getting in? With college application season fast approaching, it’s a question that weighs heavily on the minds of many high school seniors and their parents.

Academics and policymakers are also transfixed by the power of the BA and its potential to boost workforce productivity and expand opportunity for the disadvantaged. A case in point: our colleagues at Brookings’ Hamilton Project released a series of papers today on improving college outcomes through financial aid policies.

The attention paid to 4-year colleges is justified. In terms of earnings alone, it pays to be a BA holder: according to Hamilton Project estimates, the average college graduate earns over a lifetime $570,000 more than the average individual who receives only a high school diploma. But BAs should not become the exclusive focus. If we want to make big strides in social mobility, we might in fact be better off focusing on the BA’s under-appreciated sibling: the Associate degree. Earning an Associate degree alone can increase earnings by between 13% to 22%.

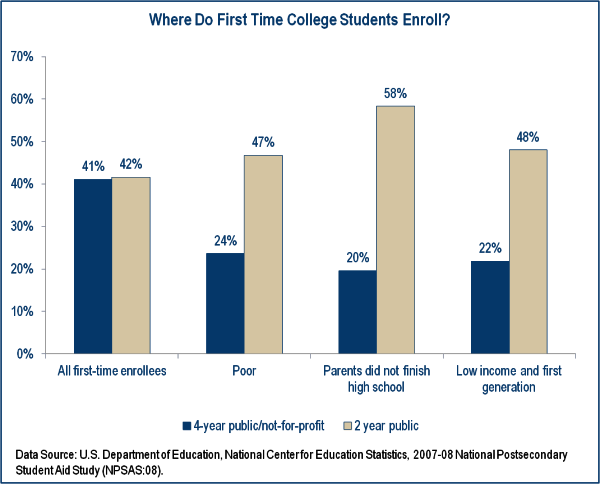

The first contact with higher education for most college-bound students from disadvantaged backgrounds is the local community college. While community colleges enroll about the same number of new students as 4-year colleges, they enroll a much higher proportion from less advantaged backgrounds:

Of course, some of these low-SES community college enrollees are the “high-achieving, low-income students” documented by Hoxby and Avery – that is, students who had the credentials to attend a more selective school but, for a variety of reasons, did not apply. We certainly need to make greater efforts to get more of these students into more selective colleges – and recent moves by the administration to tie federal funding to access criteria are an important step in the right direction.

For many, however, community college will remain the most appropriate option for postsecondary learning. But there is a growing problem: the gap between enrollment and graduation.

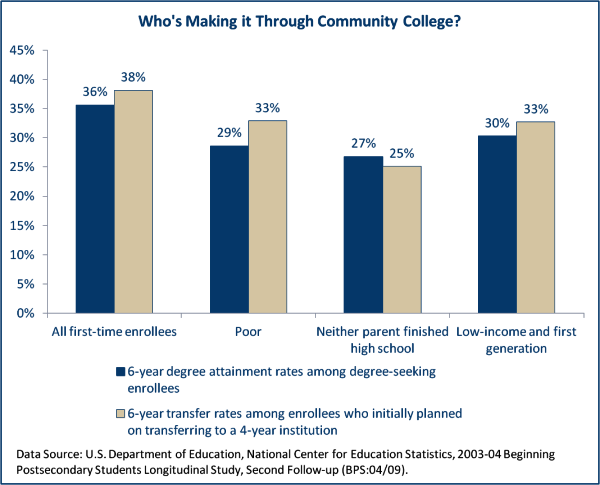

Community colleges suffer from low completion rates, especially among students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Just 36% of all degree-seeking community college students enrolling in 2003 earned a formal degree within the following 6 years. For students from low-SES backgrounds, these rates were even lower. More troubling still were the low transfer rates among community college students who initially planned to transfer to a 4-year college. Again, the likelihood of transferring was even lower among first-time enrollees from disadvantaged backgrounds:

There is huge scope for improving mobility outcomes through the development of the community college system, especially by boosting Associate degree attainment rates and helping students transfer to 4-year institutions. And many states, schools, and nonprofits have begun to tackle these challenges head-on through a variety of innovative programs, including experimental performance-based scholarships and more flexible college curriculums (e.g., stackable credits and career pathways). Much more is needed, though. The question policymakers should perhaps be asking themselves this fall is: what’s the secret to getting through community college?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Community College May Hold the Key to Social Mobility

October 21, 2013