Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, exports from Germany and other EU countries to out-of-the-way places like Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia have risen sharply. As this blog has documented, these exports aren’t destined for domestic demand in these places, but are transshipments designed to circumvent Western export controls on Russia. The magnitude of these transshipments is substantial. Evidence based on German export data suggests transshipments via third countries fully offset the fall in direct exports to Russia, so that the flow of German goods to Russia never really diminished.

Intuitively, if Russia can circumvent Western export controls via transshipments, it’s highly likely that China can do the same vis-à-vis U.S. tariffs. Indeed, even before the second Trump administration, there was evidence that China used Mexico and Vietnam, to name just two places, as transshipment hubs for goods destined for the U.S. This blog reports on the latest Chinese trade data through May 2025, which suggest that the fall in China’s direct trade surplus with the U.S. has been fully offset by a rise in its trade surplus with other countries. Since demand in these places is unlikely to have risen sharply—not least since trade tensions are weighing on demand globally—this likely points to heavy use by China of transshipments to circumvent U.S. tariffs.

China’s transshipment of goods around US tariffs

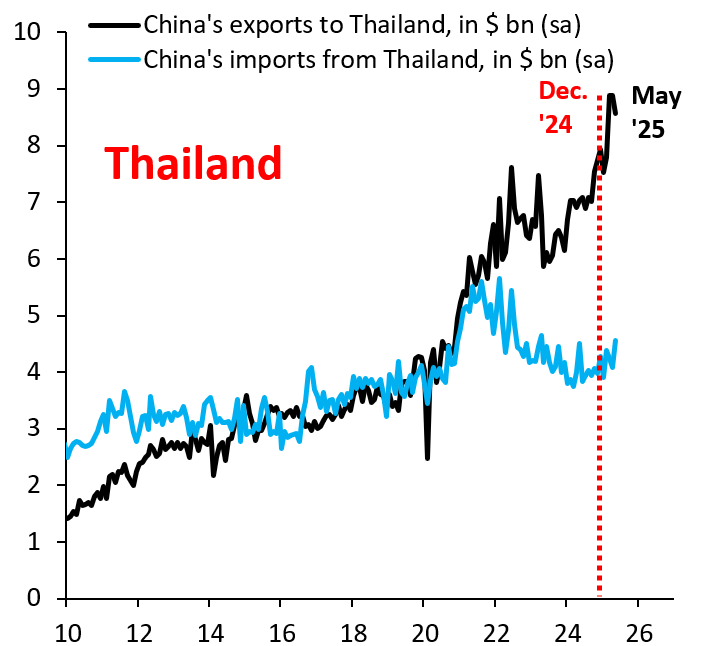

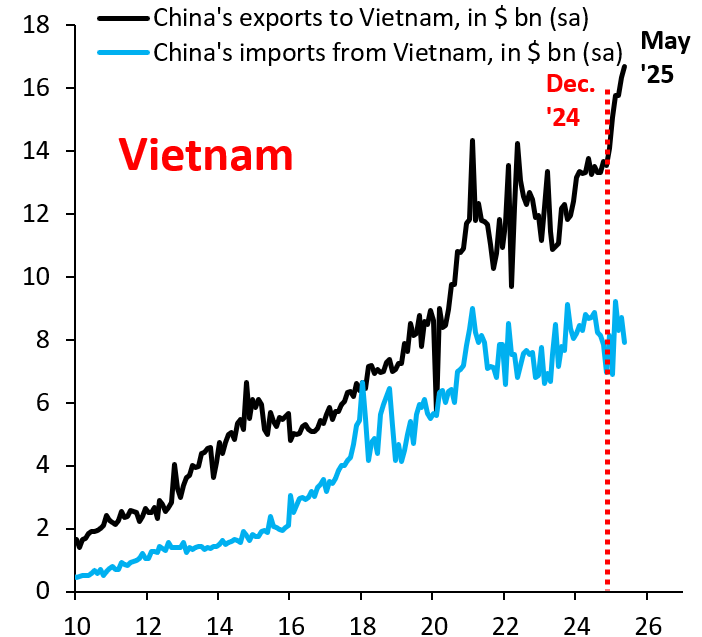

China publishes seasonally adjusted data for its exports to and imports from its main trading partners. These include trade with the EU, the U.K., Japan and many emerging markets. The only notable exception from these data is Mexico, for which bilateral data are only available—with a lag—from the IMF Direction of Trade Statistics. Figures 1 and 2 show China’s monthly exports to and imports from Thailand and Vietnam, respectively, in billions of dollars per month. It is clear from both charts that China’s exports to both countries began to rise very sharply—and anomalously—in early 2025, ahead of U.S. tariffs. Looking at these data, it seems like China knew tariffs were coming.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

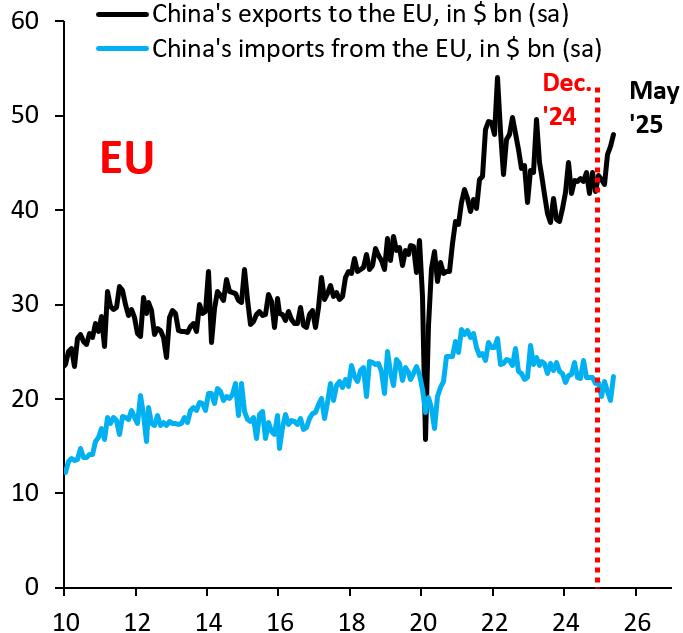

Of course, these data don’t shed light on whether these goods ultimately end up in the U.S. However, it seems unlikely that domestic demand in Thailand or Vietnam would have risen so sharply right around the time the U.S. imposed tariffs. If anything, uncertainty around tariffs is weighing on global activity, making any surge in trade quite suspect. As a result, this is strong circumstantial evidence—similar to EU exports to Central Asia in the case of Russia—that transshipments are happening. This phenomenon doesn’t look like it’s restricted to emerging markets. China’s exports to the EU have also seen a sharp rise year to date (Figure 3). Maybe there’s a greater likelihood that at least some of these exports are genuinely destined for EU consumers—the EU is a much larger economy—but even here the spike in Chinese exports right at the start of 2025 looks suspect.

Source: Haver Analytics

Source: Haver Analytics

How economically meaningful are these transshipments? When you add up China’s trade surplus to 14 countries for which it publishes seasonally adjusted export and import data and compare the resulting trade surplus to its surplus with the U.S., the substantial drop in its surplus with the U.S. is more than fully offset by a rise in its surplus with others (Figure 4). This raises the possibility that transshipments to the U.S. are more or less fully offsetting the fall in direct exports to the U.S., i.e., that tariff circumvention is considerable.

The underlying question here is whether these transshipments mean tariffs aren’t working. No doubt the U.S. is leaning on countries like Thailand and Vietnam to clamp down on these transshipments. It is therefore early days and premature to see this as a sign that U.S. tariffs aren’t putting pressure on China. Indeed, as we argued in our last blog, U.S. tariffs are a deflationary shock for big net exporters of goods like China and the eurozone. The fact that these transshipments are happening in such size underscores that point. China’s manufacturing machine is seriously impacted by U.S. tariffs. The fact that transshipments are happening at such size also helps explain why the inflationary impact from tariffs has so far been muted. After all, these data suggest that Chinese goods are still reaching the U.S., just that they are coming via more complicated routings. As the U.S. leans on transshipment hubs, the inflationary impact from tariffs is likely to build.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

China’s transshipment of goods to the US

June 20, 2025