Editor’s note: The paper first appeared in

Look East, Act East: Transatlantic Agendas in the Asia Pacific

, a report by European Union Institute for Security Studies. Read an excerpt below.

China’s ascendance as a major power and its implications for the world economy, global governance and international security continues to be a source of major debate. The scope and rapidity of China’s ascent have placed China at the centre of deliberations over international strategy. There are few historical precedents for the spectacular pace of China’s economic advance, and the growth of its comprehensive national power has generated considerable unease. At the same time, by the acknowledgment of its senior leadership, China’s overall development remains ‘unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.’ The extreme concentration of economic and political power in the hands of state-owned enterprises, glaring income inequality and pervasive corruption, industrial overcapacity fuelled by local and provincial interests, widespread environmental degradation and an underdeveloped legal and institutional framework highlight the consequences of unregulated growth presided over by highly protected elites almost entirely removed from public scrutiny. To numerous observers, the lack of accountability and transparency and the inability or unwillingness of central leaders to address the inequities of Chinese development reveals a system in disarray.

China’s international position provides an instructive parallel to many of these in¬ternal concerns. After decades of uninterrupted economic growth, China’s global footprint is inescapable. All states recognise the gravitational pull of the Chinese economy, but many remain wary about China’s grudging, partial accommodation to extant international norms. Chinese leaders repeatedly emphasise their fundamental commitment to peaceful development and heightened cooperation with outside powers. But China’s self-protective stance on a range of international issues and rising nationalist sentiment underscore the gap between China’s declared aspirations and its actual behaviour. Sadly, long-submerged historical disputes have resurfaced in other Asian states as well, renewing volatile animosities that threaten to destabilise the region.

At the same time, Chinese strategic specialists argue that the established powers (particularly the United States) are unprepared to accord China genuine legitimacy as a major power, openly accusing the US of seeking to constrain or undermine China’s rise, either unilaterally or in concert with others. There is a receptive popular audience within China for such arguments. The corollary to these expressed grievances is that outside powers must acknowledge and accommodate to China’s growing strength, rather than vice versa. But other Chinese commentators contest these arguments, contending that enhanced international status requires China to develop normative authority appropriate to its growing economic and military power. Underlying these academic debates are deep, unresolved questions about how Chinese leaders and citizens envision long-term relations between China and the outside world, which are closely linked to China’s internal political and social evolution.

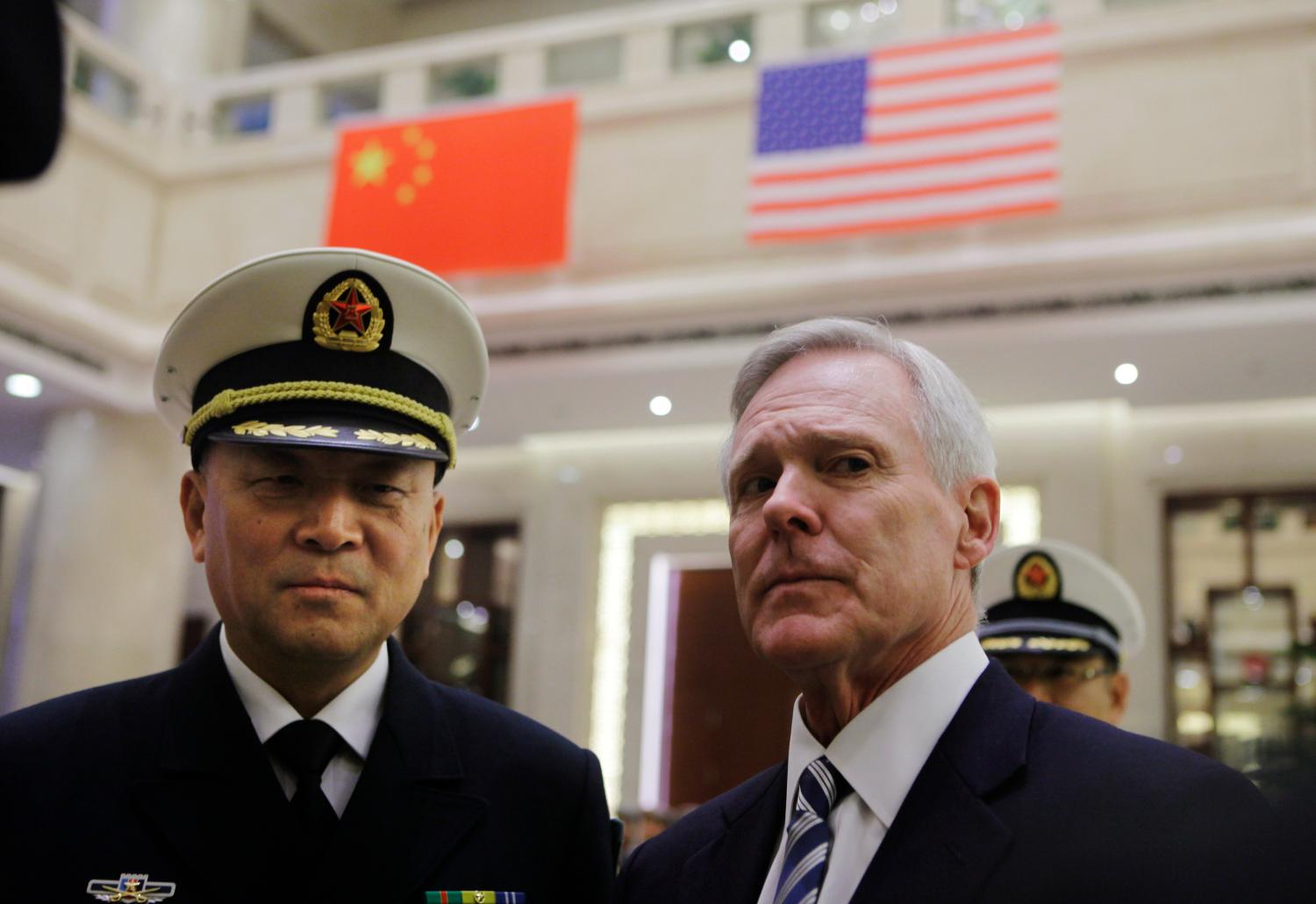

China’s rise and its consequences for the international and regional order are not solely issues for regional actors or the United States to contemplate, nor are the outcomes of this process foreordained. China’s economic imprint is global rather than regional. Growing numbers of Chinese nationals now live and work across the Greater Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and various sub-regions of Asia. Its diplomatic and corporate profile is evident across all continents. China’s involvement in peacekeeping operations, military-to- military relations, and naval diplomacy is also increasingly diverse, and deemed a quiet success story by the military leadership.3 Thus, lasting accommodation is best realised through mutual political and strategic understandings and development of shared international norms, but none of this will come easily, or soon.

As major centres of global power with a shared stake in an inclusive, rules-based international system, America and Europe have long sought to address the risks and opportunities associated with China’s rise. However, policy coordination between the US and EU is far from satisfactory, in part reflecting their asymmetric roles in Asia and the Pacific. America retains a dominant security position in the region but there is no equivalent involvement by European states. In addition, there is widespread concern in European capitals that American preoccupation with the rise of China and a nascent Sino-American strategic competition have supplanted traditional US policy interests in Europe. But neither the US nor the EU wishes to see an erosion or breakdown in existing security arrangements on which the region’s prosperity and stability have long depended. The need for enhanced American and European consultations over China’s longer-term future and the parallel need to craft complementary US and European policy approaches (without fuelling Chinese perceptions of malign intent) is thus a pressing political and strategic issue that warrants far more attention.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).