Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

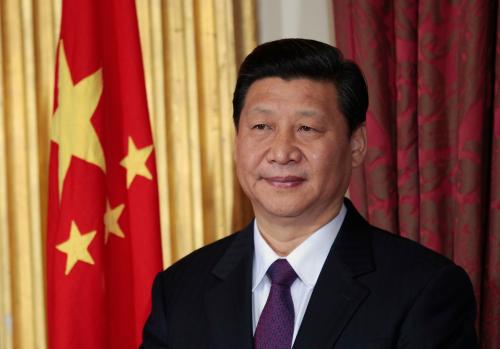

China is again at crossroads in its domestic politics. After becoming party boss in 2013, President Xi Jinping surprised many people in China and around the world with his bold and vigorous anti-corruption campaign and his impressively quick consolidation of power.

Within two years, Xi’s administration purged about 60 ministerial-, provincial- and senior military-level leaders on corruption charges, including ten members of the newly-formed 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In 2013 alone the authorities handled 172,000 corruption cases and investigated 182,000 officials –– the highest annual number of cases in 30 years.

In an even bolder move Xi purged three heavyweight politicians: former police czar Zhou Yongkang, who controlled the security and law enforcement apparatus for ten years; former Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission Xu Caihou, who was in charge of military personnel affairs for a decade; and Ling Jihua, who was head of the General Office of the CCP Central Committee and oversaw all of the activities and document flow of the top leadership during the era of President Hu Jintao. These moves to clean up corruption in the party leadership have greatly bolstered public confidence and support for Xi.

Equally significant is the consolidation of Xi’s personal power: he holds the top position in many leading central groups, including important areas such as foreign affairs, financial and economic work, cyber security and information technology, and military reforms. Altogether, Xi occupies a total of 11 top posts in the country’s most powerful leadership bodies.

Xi’s ascent to the top leadership rung raises a critical question: will his ongoing concentration of power reverse the trend of collective leadership, which has been a defining characteristic of Chinese elite politics over the past two decades? In post-Deng China the party’s top leaders, beginning with Jiang Zemin of the so-called third generation of leadership and followed by Hu Jintao of the fourth generation, were merely seen as “first among equals” in the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC), the supreme decision-making body in the country. Many observers argue that Xi’s leadership –– his style, decision-making process, and public outreach –– represents the “reemergence of strongman politics.”

But it is one thing to recognize Xi Jinping’s remarkable achievements in consolidating power in just two years as top CCP leader and quite another to conclude that he has become a paramount and charismatic leader in the manner of Mao Tse-Tung or Deng Xiaoping. The power and charisma of Mao grew out of his extraordinary leadership in revolution and war. On the other hand, despite his influence, Deng did not hold any leadership positions in the final ten years of his life except for the post of honorary chairman of the China Bridge Association. Therefore, the fact that Xi holds 11 leadership posts is not necessarily a sign of strength.

Moreover, Xi’s concentration of power and strong political moves has more to do with the factional makeup of the PSC than with his authority and command. In the post-Deng era, two major political coalitions associated with former party bosses Jiang and Hu (who both still wield considerable influence) have been competing for power and influence. The former coalition was born in the Jiang era and is currently led by Xi. Its core membership consists of “princelings” –– leaders born into the families of revolutionaries or other high-ranking officials. Both Jiang and Xi are princelings themselves.

The latter coalition, known as the Hu-Li camp, was previously led by Hu Jintao and is now headed by Premier Li Keqiang. Its core faction consists of leaders who advanced their political career primarily through the Chinese Communist Youth League, as did both Hu and Li. Leaders in this faction, known as tuanpai, usually have humble family backgrounds and leadership experience in less developed inland regions.

During the 2012 leadership transition, the Jiang-Xi camp won an overwhelming majority of seats on the PSC. It secured six of the seven spots, while only Li Keqiang now represents the Hu-Li camp on the PSC. This six-to-one ratio in favor of the Jiang-Xi camp is a very important political factor in the present-day Chinese leadership. It gives Xi tremendous power. It explains why he can implement new initiatives so quickly.

Yet, the five members of the PSC who are Xi’s political allies are expected to retire, as a result of age limits, at the 19th National Party Congress in 2017. It will be very difficult, if not impossible, for the Jiang-Xi camp to maintain such an overwhelming majority in the next leadership transition because the Hu-Li protégés are far better represented in the current Central Committee –– the pool from which members of the next Politburo and PSC are selected. The Hu-Li camp will not remain silent if Chinese elite politics returns to the Mao era of zero-sum games where the winner takes all. In fact, Xi’s strong anti-corruption campaigns have already been widely perceived, rightly or wrongly, as being driven primarily by factional politics; thus he has created many false friends and real enemies and an unpredictable and dangerous political situation for the country.

Though this relentless anti-corruption campaign has already changed the behavior of officials (the sale of luxurious cars and watches has dropped dramatically, for example), it risks alienating the officialdom—the very people on whom the system relies for effective functioning. Xi’s actions also undermine vested interests in monopolized state-owned business sectors such as the oil industry, utilities, railways, telecommunication, and banking –– the “pillar industries” of state power. As of 2015, China’s flagship state-owned enterprises were required to cut the salaries of senior executives by as much as 40 percent. Meanwhile, a large scale reshuffling and retirement of senior military officers has been underway and this political move could be potentially very costly to Xi. His politically conservative approach, relying on tight political control and media censorship, has also alienated the country’s intellectuals.

At the same time, Xi is very popular among three important groups in China. First, the general public applauds Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, his decisive and effective leadership role, and his “Chinese dream” vision—defined as the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation and the opportunity to realize a middle-class lifestyle. Second, private entrepreneurs are beneficiaries of Xi’s economic reform agenda, as he defines the private sector as the “decisive driver” of the Chinese economy. The ongoing financial reforms now give more loans to small and medium size private firms. And third, members of the military, particularly younger and lower level officers, are inspired not only by Xi’s global feistiness and his nationalist spirit in confronting Japan and others but also by the new opportunities for promotion and prestige.

Apart from political elite infighting, there are many serious problems within China that could trigger a major international crisis: slowing economic growth, widespread social unrest, cyber system outage, and heightened Chinese nationalism particularly in the wake of escalating tensions over territorial disputes with Japan, some Southeast Asian countries and India. Taiwan’s 2016 presidential election, in which the pro-independence party will likely win, might also instigate strong reactions on the mainland.

This does not necessarily mean that Xi intends to distract from domestic tensions with an international conflict; contemporary Chinese history shows that trying to distract the public from domestic problems by playing up foreign conflicts has often ended in regime change. Yet, Xi may be cornered into taking a confrontational approach in order to deflect criticism.

The broad public support that Xi has recently earned should allow him to concentrate on a domestic economic reform agenda and avoid being distracted by foreign disputes and tensions that could otherwise accompany the rise of ultra-nationalism. But one can also reasonably argue that Xi may use his political capital on foreign affairs, including a possible military conflict, which may help him build a Mao-like image and legacy.

Leaders in the United States and India should grasp the dynamics of Chinese domestic politics, especially elite cohesion and tensions. Three policy recommendations are in order. First, both the United States and India need to clarify to the Chinese public that they neither aim to contain China nor are they oblivious to China’s national and historical sentiments; that would help reduce anxiety and possible hostility in their relationship with China. Second, while President Barack Obama and Prime Minister Narendra Modi should continue to cultivate personal ties with Xi, they should also develop broader contact with other prominent Chinese leaders. Enhanced contact with Chinese civilian and military policymakers can help the United States and India better understand the decision-making processes and domestic dynamics within China. Finally, a solid consensus amongst U.S. allies in the region could reassure China that the United States and India are not only firmly committed to their regional security framework in the Asia-Pacific, but that the two countries are also genuinely interested in finding a broadly acceptable agreement to the various disputes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).