The 2018 Beijing Summit of the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) has been defined by Beijing as its most important home diplomatic event this year, with 53 out of 54 African countries represented, leaving out only Swaziland, which still maintains diplomatic relations with Taiwan. The grandeur of the treatment for African leaders also shows the importance of the event, including the level of protocol, the diversity of the commitment, and a fully mobilized public relations machine to sing praise for the Sino-Africa friendship. Even Beijing’s infamous pollution was forced to cooperate: The government implemented stringent control measures to engineer an artificial blue sky, created for the most important political events, like the 2008 Olympics and the 2014 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

Beijing urgently needs a diplomatic win. The difficult political and economic position from the trade war with the United States has tarnished the wisdom of China’s assertive foreign policy and the glory of the superpower image that Beijing had tried to project. The ever-growing criticisms of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, such as it being “neo-colonialism” or a giant “debt trap” for the recipient countries, have raised doubts about the massive Chinese economic and infrastructure campaign, leading to the cancellation or the downsizing of major projects in Pakistan, Malaysia and Myanmar. At this critical juncture, FOCAC serves as the key event to repair China’s reputation, restore tarnished confidence, and reconsolidate China’s message.

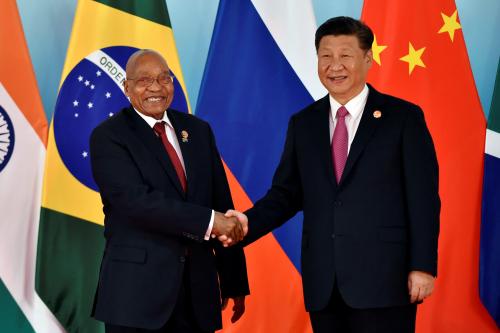

As expected, Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a keynote speech at the summit, illustrating the priority areas of China’s engagement with Africa in the coming three years. In his speech, Xi announced Eight Actions to succeed his 2015 “Ten Cooperation Plans” at the 2015 FOCAC Johannesburg Summit. He renewed another financing commitment of $60 billion to Africa, although the changing composition of the committed financing reflects key recalibrations by China.

Stagnating financial pledge and decreasing concessionality

Traditionally, China had a pattern of doubling or tripling recent FOCAC pledges: from $5 billion in 2006 to $10 billion in 2009, to $20 billion in 2012, and to $60 billion in 2015. Deviating from this pattern, China’s financing pledge at the Beijing Summit remains the same as three years ago. While no one expects China’s financing pledges to continue to double or triple indefinitely, the stagnation of any growth indirectly reflects a cautious attitude on China’s part. This could be attributed to a few factors, including the negative impact of the trade war on the Chinese economy, the rising concern over its capital outflow, the continued growth of bad debt in China, as well as the domestic criticism of Beijing squandering taxpayers’ money to buy foreign affinity.

The most noticeable change to Beijing’s financing pledges lies in its composition. Judging by the language alone, the overall level of concessionality and preferentiality of the Chinese financing is decreasing. To begin with, the amount for grants, zero-interest loans, concessional loans, and credit lines have decreased from the $40 billion in the 2015 commitment to $35 billion. Concessional loans, which were combined with export credits to reach $35 billion in 2015, are now put in the same category with grants and zero-interest loans in 2018. Although the total of these three items (grants, zero-interest loans, and concessional loans) reaches $15 billion, it remains a question whether the free grants and zero-interest loans will match the 2015 level ($5 billion). Although China still pledges $20 billion of credit lines, the credit is no longer specifically confined to the export credit as it was in 2015, and there is no mentioning of such credits being preferential. In addition, the specification from 2015 on the enhancement of the concessionality of the concessional loans is removed from China’s pledges this year. This could be the most indicative of China’s heightened concerns about the returns and commercial viability of the Chinese financing.

Morphing from loans to investment

China is committed to set up a $10-billion special fund for development financing, reflecting China’s changing model of financial engagement in Africa. Evolving away from the previous “resources for infrastructure” model, China has been increasingly keen on utilizing financing provided by Chinese development finance institutions, such as China Development Bank and China-Africa Development Fund, to support Chinese companies’ equity investment in Africa.

To diversify the pool of Chinese investors in Africa, Beijing has pledged “to encourage Chinese companies to make at least $10 billion of investment in Africa in the next three years.” In the past, this was not included in China’s FOCAC commitments, illustrating a conscious push by the Chinese government for more Chinese companies, including private investors, to invest in Africa. The $10 billion is included in the $60 billion of support China pledges, but the specification is that such investment will be made “by companies.” Most likely, Chinese state financial institutions will encourage and induce such investment by contributing to or jointly funding such projects.

Chinese investments in Africa remain small

The new commitment to boost Chinese investment to Africa inadvertently reveals an inconvenient truth in China’s economic engagement in Africa. Despite all the enthusiasm about China investing more in Africa, the actual volume of Chinese investment in African remains small, both in absolute terms and in comparison with other regions. In 2017, China’s foreign direct investment toward Africa was $3.1 billion, 2.5 percent of China’s global foreign direct investment that year, the smallest among all continents. In comparison, Chinese companies’ acquisition in Latin America in 2017 alone was $18 billion. In terms of investment stock, Chinese investment in Latin America has surpassed $200 billion by the end of 2017, twice that of Chinese investment in Africa, which surpassed $100 billion by the end of 2017.

The composition of Chinese financing also reveals another, perhaps deeper, inconvenient truth. Given that China pronounces that it has fulfilled its pledged $60 billion of financing to Africa under the 2015 FOCAC commitment, (including $5 billion for grants and zero-interest loans), and given the Chinese foreign direct investment to Africa in 2016 ($3.3 billion) and in 2017 ($3.1 billion) totaled $6.4 billion, what the numbers do manifest is that: The overwhelming majority of Chinese financing to Africa are neither grants nor investment, but loans of various forms. China may not be the biggest creditor of Africa, but this serves to substantiate the wide-spread conviction that China is creating more debt for Africa (although the Chinese counterargument has been that the long-term economic capacity building effect of the Chinese loans significantly outweighs their downsides).

Diversification of African exports promised, but…

The Beijing Summit also includes a $5 billion special fund for financing Chinese imports from Africa. Indeed, in the “Trade Facilitation” action, China declares its decision to “increase imports, particularly non-resource products from Africa.” This has consistently been a claim by the Chinese government, but its ability to increase non-resource imports from Africa also depends on the region’s ability to generate such products. Chinese official statistics no longer provide a detailed breakdown of categories of Chinese imports from Africa. However, the top African exporters to China are indeed resource-rich, ranking down from South Africa to Angola, Zambia, Republic of Congo, and Democratic Republic of Congo in 2017. If South Africa, China’s biggest trading partner on the continent and the largest African exporter to China, could serve as an example, according to data from China’s Ministry of Commerce, natural resources (mineral resources and base metals) together accounted for 86.2 percent of the country’s exports to China in 2017, up from the 83.7 percent in 2016.

What does this mean?

There is still a long way to go for the diversification of African exports to China. In brief, judging from the volume and composition of China’s 2018 FOCAC financial pledges to Africa, China’s commitment remains strong, but appears to be more cautious and calculating than its pledges from the past summit. The concessional side of Chinese financing is being moderated, while China has grown visibly more focused on the commercial and viability aspects. From the traditional model of “resources for infrastructure,” China appears to be morphing toward the next stage: equity investment by a more diverse group of investors supported by state development finance. Meanwhile, Africa still has major catch-up to do to attract more Chinese investment and to diversify its trade relations with China.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

China’s 2018 financial commitments to Africa: Adjustment and recalibration

September 5, 2018