Yesterday we noted that new value-added trade data, compared to traditional trade statistics, suggest that the greatest threat to U.S. manufacturing may come from other advanced economies rather than from developing countries with low labor costs—like China. Today, we want to illustrate the point with a look at the iPhone 3G S.

As shown in a voxeu post by economist Yuguing Xing, the iPhone cost $178.96 to manufacture in 2011. In keeping with that, traditional trade accounting adds $178.96 to the U.S.-China trade deficit given that traditional trade statistics credit countries with the full value of an exported final product, even if its main activity is assembling parts received from elsewhere. Because Apple assembles its iPhones in China and then ships the final phone to the United States, China gets the full credit. However, as we suggested yesterday, that’s not quite right.

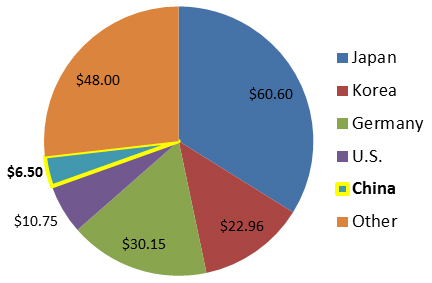

As it happens, the iPhone 3G S is a truly international product that contains content from multiple nations. In fact, by breaking down the iPhone by the value of each component, Andrew Rassweiler shows that only $6.50, or 3.6 percent, of the value of the iPhone is actually attributable to China. The rest of the phone’s value reflects components (such as the touchscreen, Bluetooth, and semiconductors) which are imported by China and have nothing to do with Chinese manufacturing. In fact, the few high value components manufactured in the U.S. including the memory card, audio device, and Bluetooth are worth 60 percent more than what the Chinese economy actually receives from assembling the iPhone!

Value of iPhone 3G S component by contributing country, 2009

Andrew Rassweiler, “

iPhone 3G S Carries $178.96 BOM and Manufacturing Cost, iSuppli Teardown Reveals

.” iSuppli, 24 June, 2009.

So if China doesn’t represent much of the value of manufacturing the iPhone, what countries do? Japan, South Korea, and Germany. Together these three countries make up over 63 percent of the value of the iPhone. These developed economies are masters of advanced manufacturing and have relied on shrewd business practices along with cutting edge technologies and smart workforce training programs to sustain their manufacturing sector. The outcome of which is that they, not us, are adding manufacturing value to what essentially is an American invention.

As any good journalist knows, nothing sells better than a scary chimera. And with the rapid growth of Chinese assembly workers, the Chinese Dragon is an understandable target. Yet if the United States wants to recover even a fraction of the jobs that have been lost in the manufacturing sector it’s going to have to get serious about who its real competitors are and what they are doing that we are not. When we do that we will likely recognize that our most serious competition is delivering high-value advanced goods and competing aggressively—including with strategic public-private innovation investments, comprehensive worker training, competitive taxes, and trade policy. Moreover, most these initiatives exist in dense urban innovation systems that create pools of skilled workers and ample opportunities for R&D and technology diffusion. Trying to reclaim low-wage assembly jobs from developing countries is not only futile but a harmful distraction. American manufacturers and policymakers need to focus on global value-creation and put in place the private- and public-sector strategies that will enable U.S. manufacturing ecosystems to compete more successfully.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

China: A Manufactured Chimera? Part Two

May 22, 2014