As far back as the 1940s, California’s leaders knew they had a climate problem. Back then and during the decades that followed, Angelenos barely had to look up to see the smog filling the Los Angeles Basin, and locals knew better than to let their children step outside during especially bad days. Smog from fires in dumps choked the Bay Area, and in the 1970s, pollution-wrought birds would periodically rain down on the San Diego Freeway. When smog became a defining political issue, automobiles emerged as its malevolent catalyst.

Today, even as cars have become more energy efficient and other pollution mitigation efforts have taken hold, California’s transportation system still creates environmental risks for the state’s residents. Transportation emits more greenhouse gases (GHG) than the next two highest-emitting sectors combined, while at the same time, wildfires threaten and often devastate the state’s metropolitan communities, many of which developed alongside an ever-expanding roadway network.

Then and now, California’s leaders heard the cries of both its environmental advocates and everyday citizens. In 1967, then Governor Ronald Reagan signed the Mulford-Carrell Air Resources Act, which created the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and set state air quality standards. Forty years after those legislators fought back smog, in 2006, lawmakers took on GHG emissions with AB 32: the California Global Warming Solutions Act. Those laws and their successors include goal after goal in pursuit of reducing GHG emissions, particularly from the transportation sector.

In recent years, California has tried to legislate an approach that connects mitigation to resilience. The most recognizable laws addressing those interlocking goals are SB 375 in 2008 and SB 743 in 2013. While they also contemplate strategies to decarbonize fuel and vehicles, make no mistake: These state laws explicitly aim to lower vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and counteract the ill effects of automobile-centric development by encouraging less sprawling land use.

The Golden State has certainly built a gilded reputation for such lawmaking. Thought leaders from academia, policy advocacy, and government often point to California as an example of how to use legislation and executive rulemaking to purposely address transportation’s climate impacts. From a procedural point of view, the reputation is well earned: California is doing things.

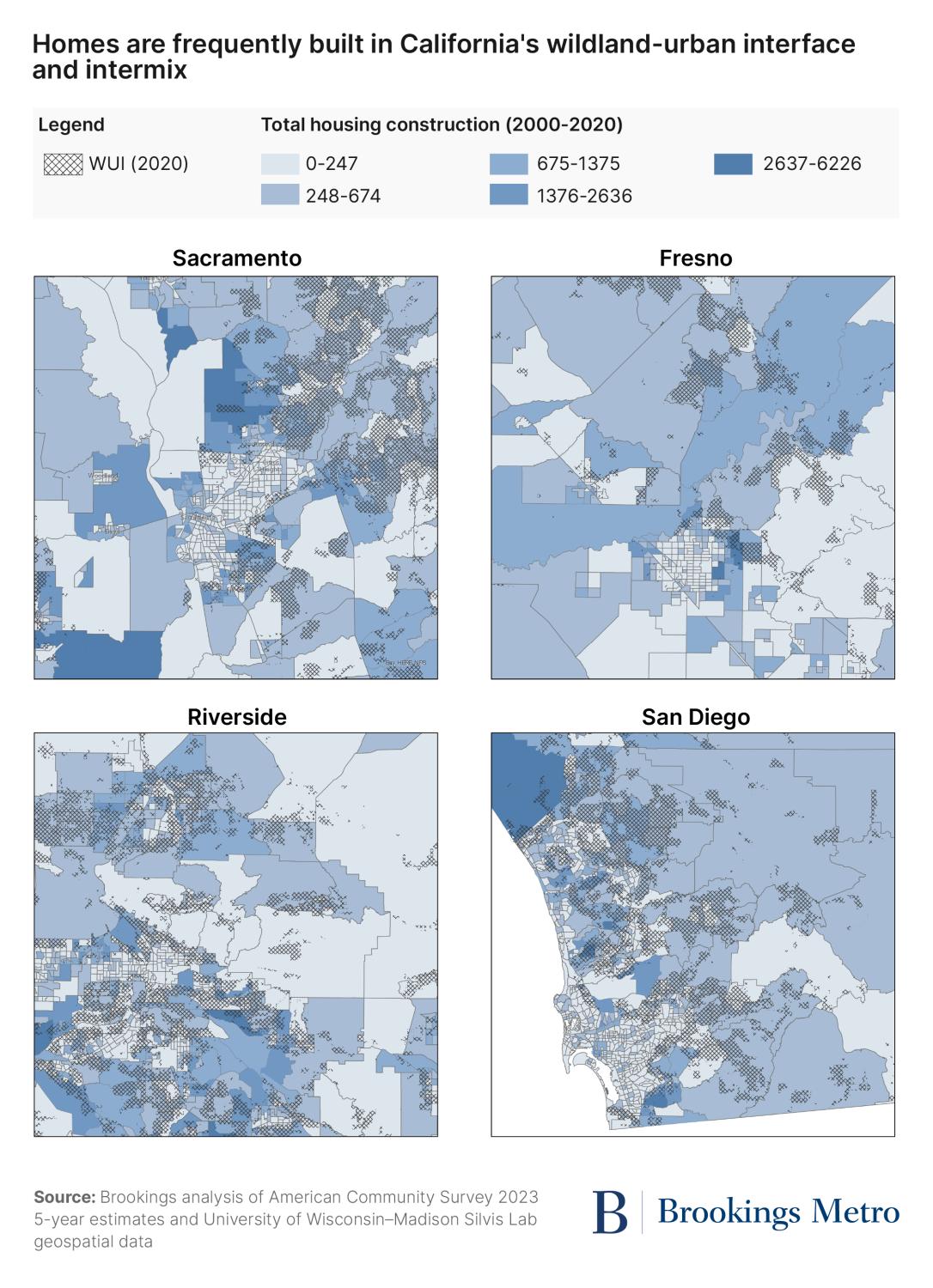

However, this reputation can seem superficial when interrogating actual progress on the ground. Unlike the energy and buildings sectors, the transportation sector is holding the state back from reaching its overall emissions reduction goals. Crucially, most of the decline in transportation emissions is from households switching to electric and hybrid vehicles, not from people actually driving less. Instead, Californians are driving more, and neither residents nor businesses have stopped sprawling outward. Since 1990, nearly half of all housing was built in the most wildfire-prone outskirts of metropolitan areas.

Meanwhile, the administrative regime that California legislated into existence has tested the technical and staffing capacity of local, regional, and even state officials. SB 375, SB 743, and related laws set up an often-inscrutable network of planning exercises, environmental permitting requirements, and legal exemptions for local leaders to discern and execute. Yet for all the plans and documents the laws mandate into existence, the state offers too little funding to deliver on its vision and has too little authority to enforce all the goals proclaimed in the documents.

The implications of California’s failure to improve land use are significant, extending beyond ambitious climate goals. California still isn’t building enough housing units, and the state has the prohibitive rents and high costs of homeownership to show for it. Though building in lower VMT neighborhoods alone may not solve the state’s housing shortage, the relative inability to develop those areas—often in older, infill locations—leaves officials with one less tool to address the state’s housing shortfall.1 There’s a real opportunity to use transportation- and climate-focused policies to address the state’s housing crisis while hitting its climate goals at the same time.

Considering the difference between reputation and results, this research series sets out to understand why progress has been so difficult—and what it might take to set California on a course to reach its ambitions. To do this, we conducted an extensive literature review and sat for interviews with over 20 in-state stakeholders spanning academia, all levels of government, industry, and more. Through this process, we’ve mapped the byzantine set of laws that govern what gets built, taking the perspective of both statewide and local stakeholders. Those findings make it easier to see what’s not working—and to suggest the kind of reforms that could both streamline processes and accelerate project delivery.

We will discuss our findings over a series of reports that sequentially present how we’ve diagnosed the problems and our recommended solutions. This first report explains how the state got here.

Land use offers a potent response to the environmental risks Californians face

For decades, California has been a national leader when it comes to recognizing the risks associated with greenhouse gas and other damaging emissions. The state officially targets emitting 40% fewer greenhouse gases in 2030 than in 1990, and 80% fewer by 2050. And from the state down to the local level, most officials recognize a blunt truth: There is no way to hit emissions targets without addressing the transportation sector.

Transportation is the highest-emitting sector of California’s economy. In 2022, 37.7% of all GHG emissions were from transportation—dwarfing the second-highest emitting sector, the industrial sector (19.6%). Of the emissions from transportation, nearly three-quarters were from passenger vehicles. CARB’s 2022 Scoping Plan for Achieving Carbon Neutrality dedicates the state to pursue three approaches to decarbonizing transportation: VMT, technology, and fuels.

The adoption of hybrid and electric vehicles (EVs) is one strategy in which California has seen real progress. The state started setting goals for fleet transition over a decade ago, and established fuel emissions standards for new vehicle sales. The combination of rules and consumer tastes have pushed EVs to represent over 6% of all light-duty vehicles registered in the state in 2024, and California is now the national leader in EVs as a share of all light-duty vehicle registrations. And though full turnover of California’s fleet may be slow, over a quarter of light-duty vehicle sales in 2024 were EVs.

However, low-emission vehicles are not an emissions-reduction panacea. In the Scoping Plan, CARB itself acknowledged that switching to zero-emission vehicles alone could not meet the state’s climate and air quality goals. Fleet transition takes time, and though EVs greatly reduce engine-related emissions, their greater weight can increase non-exhaust and particulate emissions, such as those from the wearing down of brakes and tires. Most critically, zero-emission vehicles are still automobiles, and they produce the same negative externalities as carbon-emitting vehicles: conversion of greenfield land to sprawling development patterns where homes are built far from all manner of destinations. Without reductions in VMT, sprawling development threatens the same climate goals that low-emission vehicles aim to support.

Shifting where Californians live and work is a more dependable approach to reach the state’s climate goals than only decarbonizing the vehicle fleet. Greater density of housing and commercial development reduces emissions by shortening distances between destinations. Conversely, when single-family homes as a share of all housing increase by just 1%, research suggests that on-road CO2 emissions per capita see a 1.5% bump.2 Sprawling land use increases carbon emissions by inducing longer trips, while density does the opposite.

Closer-proximity land use is also instrumental in insulating California against the ever-expanding risks of climate change. When metropolitan areas develop far beyond urban cores, they often reach the wildland-urban interface (WUI), where development encroaches on natural areas. Between 1990 and 2020, the WUI was home to 45% of California’s new housing; that same area hosted over 80% of houses destroyed in wildfires in roughly the same period (1985 to 2013). And at a time when much of California is in a drought, some identify sprawling land use as the most important factor forcing water use ever higher.

Changing land use can do more than reduce emissions and exposure to weather-related risks. Across the country, metropolitan development patterns have demonstrated that increasing housing supply, particularly in existing urban areas, can substantially slow rising rents and lessen the cost burden of housing. Building more homes in denser neighborhoods tends to lead to lower household transportation costs too. Californians don’t need to wonder whether this holds for them: State-level research recommends that lawmakers who want to reduce VMT and boost affordability should adopt policies to spur development in urban infill locations and inner ring suburbs. When one intervention can deliver so many benefits, it’s little wonder the state has actively attempted to marry transportation planning and land development practices.

California keeps attempting to connect transportation, land use, and housing to climate through legislation and executive action

California law leaves no question: The state views reducing VMT and promoting infill development as central to its overall climate and growth strategies. The CARB Scoping Plan sets a goal of reducing per capita VMT to 25% below 2019 levels by 2030, and 30% below 2019 levels by 2045. That same plan is also explicit that infill development and “aligning land use, housing, transportation, and conservation planning” are strategies for achieving success.

A major reason California earned its climate-focused reputation, though, is the additional bills legislators passed to adopt comprehensive land use planning, project evaluation practices, and investment strategies in pursuit of those goals.

|

Year |

Law, executive action, plan |

Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 |

Established GHG emissions reduction targets of achieving 2000 levels by 2010; 1990 levels by 2020; and 80% below 1990 levels by 2050. |

|

| 2006 | Required California to reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. | |

| 2008 | Required CARB to set GHG emissions reduction goals for each region; required regions to produce a Sustainable Communities Strategy as part of their regional transportation plan to reach their GHG emissions reduction goals. | |

| 2013 |

Eliminated level-of-service (LOS) analysis as part of California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) review; led to the introduction of VMT as a replacement for LOS and the requirement to mitigate VMT increases. |

|

| 2015 |

Established the interim target of a GHG emissions reduction to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. |

|

| 2016 | Required CARB to ensure GHG emissions are reduced to 40% below 1990 levels by 2030. | |

| 2019 | Directed the California State Transportation Agency to leverage discretionary state transportation funds to reduce GHG emissions from transportation and support climate adaptation. | |

| 2020 |

Established the goal of 100% of in-state sales of new passenger cars and trucks being zero-emission vehicles by 2035. |

|

| 2021 |

Introduced an investment framework to direct discretionary transportation funds to climate-benefitting projects; recommended 34 actions to support implementation of EO N-19-19 and EO N-79-20. |

|

| 2022 |

Required California to achieve net-zero GHG emissions no later than 2045; required California to reduce anthropogenic GHG emissions to at least 85% below 1990 levels by 2045. |

|

| 2022 |

Outlined strategies to achieve goals set out in AB 1279; established the non-regulatory planning goal of reducing per capita VMT by 25% below 2019 levels by 2030 and 30% below 2019 levels by 2045. |

|

| 2025 |

Recommended 14 actions to further support implementation of EO N-19-19 and EO N-79-20. |

|

| 2025 |

Created new CEQA exemptions for infill development; established the Transit-Oriented Development Implementation Fund to supplement VMT mitigation efforts. |

SB 375, from 2008, primarily targets the planning side. Under that law, CARB sets targets by which regions are intended to reduce their transportation-related emissions. It is then the responsibility of each region’s council of governments (COG) to prepare a Sustainable Communities Strategy (SCS) showing how they’ll reach those targets. SB 375 effectively creates a “greenhouse gas budget” for the transportation projects a COG expects to be constructed by cities and counties that compose its board.3 It’s important to note, though, that there is no enforcement mechanism if a region fails to reach its emissions targets.

SB 375 also looked to connect housing-related plans to those climate ambitions. Since 1969, the state has used its Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) to calculate the housing need in each region. The COG then allocates the total units across its member municipalities, who use their comprehensive plan—known as a general plan—to show exactly where they plan for units to be built.4 SB 375 requires the region’s RHNA plan to be consistent with the SCS, meaning—in theory—that housing will be built in places that could help the region reach its emissions targets. Yet enforcement here is also relatively weak; regions must be compliant with SCS requirements and local governments must tie the RHNA into their general plans, but there is no requirement to incorporate the SCS into local plans and no consequences if housing production fails to lower emissions.

To complement SB 375’s regional planning requirements, in 2013, SB 743 changed how governments performed environmental reviews. Before the bill, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) required real estate and transportation projects to analyze impacts on level-of-service, or effectively how congested roadways would be. SB 743 substituted a requirement to evaluate how a project might impact VMT. The law outlines a series of screening thresholds, such transit priority areas and low VMT areas, that let some projects bypass VMT analysis entirely. For projects that aren’t exempted, the project proponent is required to mitigate whatever VMT the review determines would be induced.

Lawmakers saw SB 743 as an environmental victory, and it was heralded for its potential to reduce VMT and rein in sprawling development. Transportation advocates touted the measure as one that should be replicated in every state. SB 743, however, doesn’t simply stop all projects that fail to mitigate their VMT impacts—it requires lawsuits brought by private citizens or organizations to address those issues. Furthermore, even if the analysis finds that a project will generate significant VMT, project owners can bypass mitigation completely if a “statement of overriding concern” is adopted. In more plain terms, there are workarounds for VMT-inducing projects.

Other actions continued to adjust the state’s own transportation investment policies to promote lower emissions and resiliency. A set of executive orders led the California State Transportation Agency to adopt the Climate Action Plan for Transportation Infrastructure (CAPTI) in 2021, which has led to a new evaluation system to ensure every state-built project is in support of the state’s climate goals. CAPTI also pushes the California Transportation Commission (CTC) to be “emission neutral” when it evaluates all the regional transportation plans it must approve. Combined with other supportive laws and rules, such as requiring complete streets designs on many state-funded projects, the state is unquestionably attempting to use its dollars to promote its vision.

Finally, state lawmakers continue to tinker with established laws to incentivize infill development. The 2025 budget included laws to ease the burden of environmental review (or remove it entirely) for almost any urban infill project, and instructed state agencies to set up a development-focused mitigation bank that project leads can pay into in lieu of other VMT-mitigating efforts.

The net result is an intricate, and at times inscrutable, network of planning exercises, CEQA requirements and exemptions, and funding guidelines. What’s easy to lose sight of while taking in the sheer amount of state legislation, though, is a central question: How well do these planning and permitting laws help California reach its climate goals?

California’s statewide laws are falling short of goals while overburdening local colleagues

California’s legislative and executive actions are a clear statement of intent: The state wants to reduce the total emissions and environmental risks associated with driving and certain land use patterns. The problem is one of mechanics and authority. Simply put, the planning laws, project selection rules, and funding pots aren’t doing enough.

To start, the current laws are simply too permissive of questionable transportation projects. Municipalities and their regional partners wield enormous authority to select which transportation projects are built, and the potent mix of property taxes and local option sales taxes give most locations significant fiscal clout to move forward on projects they prioritize. State climate targets should make it significantly harder for VMT-inducing projects to move forward, but a mix of legal exceptions, the CEQA amendment process, questionable modeling, and outright support by California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) district offices has been doing just the opposite. There are efforts underway to address the concerns, such as enhanced VMT mitigation bank rules, but project pipelines can be hard to change.

The enforcement regime is also relatively toothless. There are scant consequences if the projects in an SCS aren’t initiated, and even fewer if they blow past the CARB-established targets. The state offers an Alternative Planning Strategy if a region won’t hit its emissions targets, but since that route would preclude applications to the state’s competitive grant funds, regions have little incentive to admit the shortfall. Localities can and do approve many real estate developments in higher VMT locations.5 Nor are local governments penalized under RHNA when housing needs go unmet—a gap so abused that one city produced a plan that would supposedly allow new housing to be built on top of city hall. Many experts have suggested that the most prominent threat to climate-risky projects was legal action by private citizens and organizations, not the state enforcing its own targets.

To make matters worse, California could do far more with its fiscal resources. The state generated over $20 billion in motor vehicle fees and taxes in 2024, but the bulk of those funds doesn’t support climate-related goals. The CTC’s Active Transportation Program is routinely critiqued as underfunded, and the CTC’s total discretionary funds pale in comparison to the dollars Caltrans spends on maintenance, operations, and its Transportation Improvement Program, which is where many of those VMT-inducing local projects are greenlit and underwritten. While CAPTI is a positive change, a series of capacity expansions underscore how much state funding still needs to shift.

The shortcomings of state-controlled transportation funds are then exacerbated by the lack of flexible state funding for development. The dissolution of redevelopment authorities in 2012, while not without merit, left a deficit of public resources to fund infill development. Now, when major developers need civic improvements such as utility upgrades and environmental cleanup to see their projects pencil out, it’s not as easy for municipalities or the state to provide fiscal support.

Complicating matters further is the sheer compliance burden placed on local and regional staff. Since localities have land use authority, it’s their staff who are responsible for completing environmental reviews, running VMT calculations, and updating their general plan’s various elements. Regional staff have to craft their SCS and RHNA plans. Just completing these tasks is a serious burden, but the workload is made even more difficult by the need to keep up with ever-shifting state rules and regulations, some of which have little published guidance. And even if state compliance enforcement is relatively light, the threat of private legal action is ever present. With the state offering no direct funds to comply with all these rules, it’s all an enormous ask for even the highest-capacity cities and COGs.

There is no question that California’s lawmakers have exhibited real courage and detail-oriented thinking at the intersection of transportation, land use, housing, and climate risk. But without some relief for local staff, new approaches to underwriting development, and less support for questionable projects, there is a real chance that the state’s results may never match its reputation.

There’s still time for California to achieve significant shifts in travel behavior and development patterns

That California will deliver a more sustainable and resilient transportation system is not a foregone conclusion. Those who support the status quo—including major roadway builders, specific trade unions, and single-family home builders—will continue to argue their position to lawmakers, seeking to either stop or dilute proposals in the state capitol. A tranche of elected officials and the public still don’t understand induced demand or downplay climate risks, and as a result, keep requesting wider highways and development on the urban fringe.

Yet there’s reason for optimism.

California earned its national reputation as a climate innovator for a good reason. Progress in some of the previously worst-emitting sectors is a testament to the state’s robust set of laws and the high-profile stakeholders who campaigned for action. Officials have almost two decades of experience testing new approaches and processing the feedback. There is also continued energy among many state, regional, and local officials to keep pursuing time-tested transportation and land use goals. A newly announced taskforce reassessing the effects and failures of SB 375 underscores the state’s commitment to getting this right.

This series will aim to support that ongoing push to realize the state’s ambitions. In upcoming reports, we will:

- Explore the structures, institutions, processes, and both realized and unrealized outcomes that define California’s system of climate governance.

- Consider the system’s successes and failures, focusing on how it has created knock-on effects for regions and localities.

- Examine the interventions proven to achieve California’s stated goals.

- Recommend both structural and targeted policy changes that can make California’s system of climate governance both workable for locals and sufficient to meet the state’s goals.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This research series was greatly supported by colleagues at the Policy and Innovation Center. The authors would like to sincerely thank them for their time spent as thought partners and facilitating understanding of the local perspective on these issues. Their partnership made this work possible. The authors are grateful to those who provided thoughtful critiques of and comments on this report, including (but not limited to) Robert Puentes and Bill Fulton. The authors would especially like to extend their gratitude to the 27 external experts who were interviewed for this project. The authors thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Carie Muscatello for her web design, and the rest of the Brookings Metro communications team for their support as well. The authors are solely responsible for all remaining errors and omissions.

The Brookings Institution would like to thank the San Diego Foundation for its generous support of this research. Brookings Metro is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Brookings Institution and its donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- Research from University of California, Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation reveals since 2000, California has built 689,315 new homes in low and very low VMT neighborhoods, outpaced by the 993,513 in neighborhoods where VMT was high or very high. A total of 561,638 new homes were built in neighborhoods in the middle quintile for VMT.

- The authors of the cited research rely on a dataset that distinguishes fuel types, but don’t disaggregate their results.

- Technically, the SCS is integrated into the federally required Regional Transportation Plans, which eventually inform the list of projects included in the Regional Transportation Improvement Programs, which are the federal- and state-required lists of projects that will be constructed within a given time frame and under expected fiscal conditions.

- For a more comprehensive history of general plans and current context, see: https://alcl.assembly.ca.gov/system/files/2025-03/2025.03.12-intro-to-the-general-plan-info-hearing-agenda-background-paper_2.pdf

- AB 130 includes new fiscal levers that may shift the decisionmaking calculus for some local officials around neighborhoods to develop, including the roadway infrastructure. However, at time of publication, the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation (LCI) had not yet even drafted rules for public consideration.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).