Over the last decade, nearly every state in the U.S. implemented major reforms to its teacher evaluation systems. These reforms sought to use evaluation for two purposes: 1) to inform personnel decisions, such as rewarding highly effective teachers and removing ineffective ones, and 2) to provide feedback to teachers to help them improve their practice. The idea was appealing—two birds, one stone.

But new evidence undermines that idea. A recent study by Alvin Christian and me suggests that new evaluation systems have not been able to produce high-quality evaluation feedback at scale. Providing feedback to teachers is a worthy investment, but we suspect it would be more effective to focus the evaluation system on career decisions and provide the most formative feedback outside of the evaluation process.

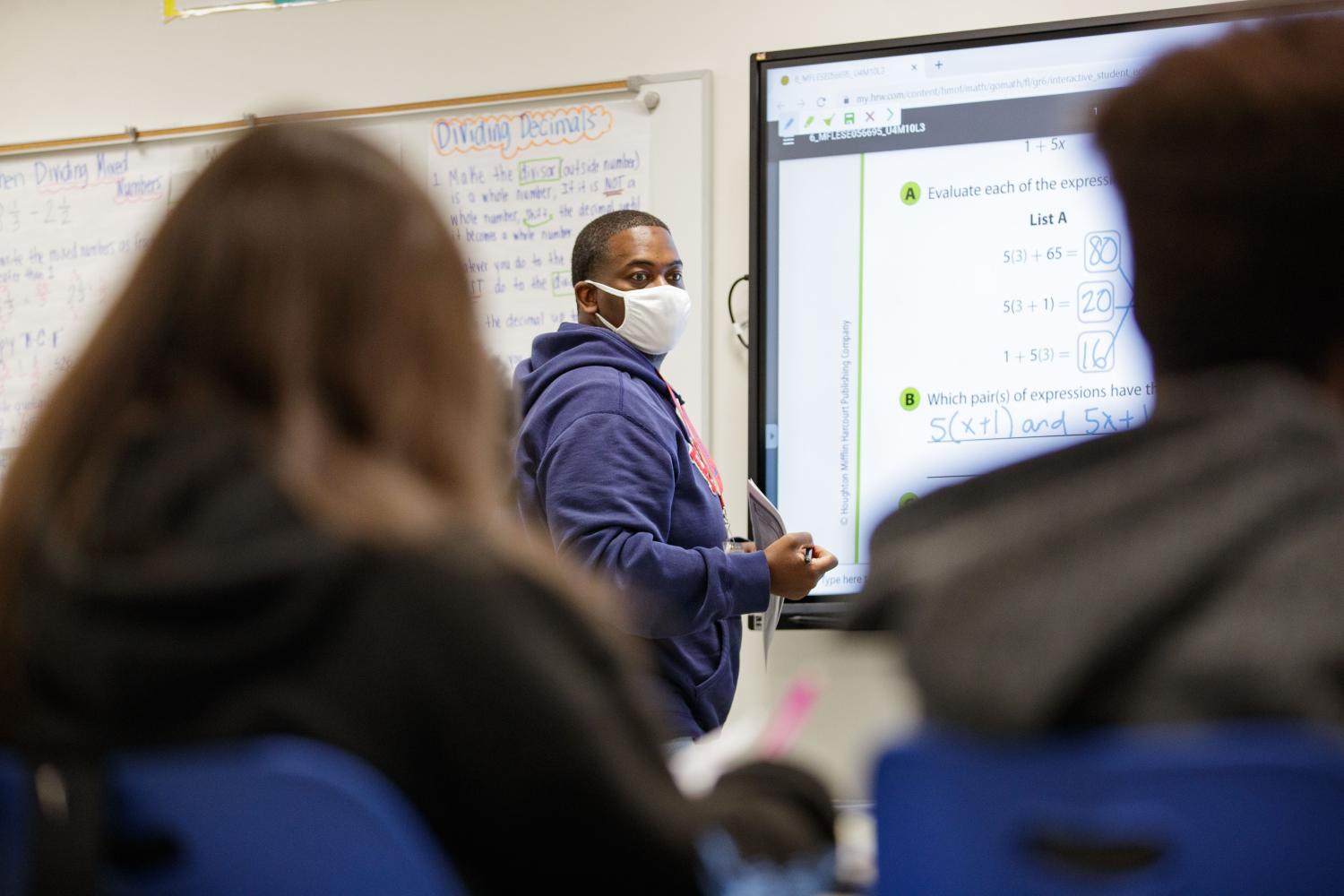

Our research is the result of a partnership with Boston Public Schools (BPS) to study their efforts to improve the feedback administrators provided to teachers as part of the formal evaluation process.

We first sought to simply gauge teachers’ perceptions of the evaluation feedback they had received through surveys. Teachers generally reported that evaluators were trustworthy, fair, and accurate, but that they struggled to provide high-quality feedback. Ultimately, only one out of four felt that evaluation feedback helped them improve their practice. In fact, most new evaluation systems require very few observations and do not mandate post-observation meetings where evaluators discuss their feedback with teachers in-person. Often, feedback was limited to a single formal written evaluation that teachers received at the end of the year.

The infrequent and ineffective nature of formal feedback should come as no surprise. Most districts have added the responsibility of conducting time-intensive teacher observations to administrators’ existing tasks without providing additional support or training to develop administrators’ capacity to deliver high-quality evaluation feedback. This was the key problem we sought to address in our study.

We worked with BPS to develop and evaluate a new administrator training program intended to improve the feedback teachers received as part of the formal evaluation process. The 15-hour administrator training program we studied was designed by experienced district-based evaluators, was grounded in adult learning practices, prioritized active learning, provided specific tools and techniques to conduct effective post-observation meetings, and was pilot tested. Moreover, data we analyzed from BPS administrator surveys suggested that they liked the training, thought it was of high quality, and intended to use practices learned during the evaluation process. But, ultimately, it didn’t work.

The results of our evaluation of the program using a gold-standard randomized field trial show the intensive training had little impact on administrators’ feedback skills or teacher performance. We find relatively precise null effects on the frequency and length of post-observation meetings, teachers’ perceptions of evaluation feedback quality, and student achievement.

While these results are discouraging, they do not mean that we should abandon formal evaluation feedback altogether. Our exploratory analyses revealed that some administrators did consistently provide high-quality feedback, but this was the exception rather than the rule. Instead, we should be more realistic about what is feasible to accomplish within the constraints of formal evaluation systems where administrators walk a tightrope between maintaining rapport with teachers, making high-stakes decisions, and providing substantive feedback. A more productive approach might be to provide feedback to support teacher improvement through other avenues.

There is good reason to think that feedback could drive teacher improvement when it is prioritized and largely decoupled from high-stakes evaluation systems. Evidence on teacher coaching programs as well as peer observation and feedback programs suggests that low-stakes forms of feedback can produce meaningful improvements in teacher instruction and student achievement. Frequent feedback is also a core practice of effective urban charter schools and high-performing traditional public schools.

Districts could, for example, harness the instructional expertise that exists in each school building through peer feedback systems. They might also employ coaches who are instructional experts with the time and skills necessary to provide frequent actionable feedback to teachers and actively involve them in assessing their own practice. Administrators still would have an important role to play by cultivating school cultures where teachers actively invite others to observe their practice, recognize that everyone has areas for growth, and share a collective commitment to continuous improvement.

Both rigorous performance evaluation and frequent formative feedback are important building blocks for promoting a strong teacher workforce. Mounting research suggests that we are watering down both practices by trying to deliver them within a single system. It’s time we more narrowly focus the goals of evaluation systems and expand investments in formative observation and feedback.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).