On Thursday, July 31, just one day before President Donald Trump’s tariff deadline, the Center for Asia-Pacific Resilience and Innovation hosted an expert discussion in Taipei on U.S. trade policy toward Japan and its implications for the Asia-Pacific. This article, authored by the three speakers, draws on insights from their discussion at the event. Read the Chinese translation of this article on the website of the Center for Asia-Pacific Resilience and Innovation.

President Donald Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” marked a shift in U.S. policy, departing from the rules-based trade order and embracing power without predictability. Trump administration official Stephen Miran has reasoned that the United States has long shouldered the burden of providing global public goods, such as the global defense umbrella and the dollar as reserve currency, at great cost. Now, allies must pay it back.

Tariffs are the chosen instrument of this recalibrated burden-sharing, used by the administration to extract compensation through trade concessions, direct investments, or even financial transfers. Just six months into its second term, the Trump administration imposed a global 10% tariff, sectoral tariffs of 50% on steel and 25% on autos, and steep “reciprocal” tariffs levied unevenly on individual countries. Protectionism has reached levels unseen in a century.

Tariffs are now being weaponized to coerce partners on noneconomic policy; for example, the White House has placed additional tariffs on countries such as Mexico, Canada, and China if they do not act on their promises to halt illegal immigration or stop the trafficking of fentanyl into the United States. Moreover, reducing American trade deficits with U.S. trading partners is now framed as a matter of national security. In these ways, tariffs are now the tool of choice for the United States to achieve wide-ranging objectives: eliminating the trade deficit, renewing American manufacturing industries, collecting revenue, and applying foreign policy pressure.

The fallout for Asia

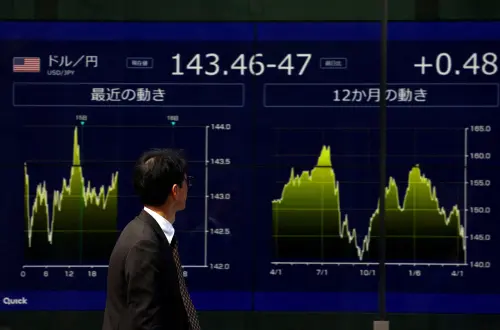

This shift in U.S. trade policy has crucial implications for the resilience of East Asian economies, especially Japan and Taiwan. As Washington arbitrarily assigns reciprocal tariffs to individual economies and negotiates bilaterally with each trading partner, previous assumptions and norms regarding the multilateral trading system have thrown the region into uncertainty.

Japan’s lopsided deal

After eight trips to the United States by Japan’s lead negotiator, Ryosei Akazawa, the United States and Japan announced a trade deal that reduced the originally announced 25% tariff to 15% on Japanese exports, including autos and auto parts, which represent a crucial part of Japan’s economy and a large share of U.S.-Japan trade. The tariff on metals will remain at 50%, and on the upcoming wave of “Section 232” tariffs to be imposed under the 1962 U.S. Trade Expansion Act for national security reasons on specific imports, the United States reassured Japan that it would not be treated more unfavorably than others.

The Japanese side agreed not to subject American autos to additional safety tests (despite low demand for American vehicles in Japan) and agreed to purchase more soybeans, bioethanol, and liquid natural gas from the United States. Moreover, Japan did not lower agricultural tariffs as part of the negotiations.

Crucially, no joint document outlining this agreement was produced. Each side issued its own fact sheet on the deal with significant gaps in interpretation, especially concerning an investment fund of $550 billion for sectors important for economic security, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, pharmaceuticals, steel, shipbuilding, autos, and critical minerals. The White House document, as well as comments by Trump and Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, portrayed Japan transferring $550 billion to the United States to be invested in projects the United States selects at Trump’s direction, with the profits being shared in a 90%-10% split favoring the United States.

The Japanese interpretation of this investment fund offered a different account, portraying Japanese government financial institutions offering equity, loans, and loan guarantees to private companies that invest in the aforementioned sectors. Moreover, equity investments were anticipated to only represent $5 billion to $10 billion.

In Japan, departing Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has been under attack by his own party members and opposition leaders because a high level of uncertainty remains. Further U.S.-Japan negotiations finally delivered a U.S. executive order on September 4 that sets in motion the process to lower tariffs on Japanese cars. An accompanying memorandum of understanding between the two countries fleshed out a selection process for the investment projects and a 50-50 profit split while project loans are being repaid. Because the United States retains the right to hike tariffs over disagreements in the implementation of the investment fund, the trade deal has not eliminated this risk for Japan.

Taiwan’s closing space

Taiwan’s economic security is deeply impacted by the United States’ new economic statecraft, especially that aimed at China. Taiwan’s export strength lies in electronics, especially information and communication technology products and semiconductors, which are now subject to U.S. Section 232 investigations. Nearly 80% of Taiwan’s exports to the United States in 2024 fall under the investigations, which the United States has framed as a national security probe. In addition, as of August 15, 2025, the United States has threatened a 100% tariff on semiconductors, with exemptions for firms committed to manufacturing in the United States, and expanded the number of products subject to the 50% tariff on steel and aluminum.

Taiwanese manufacturing supply chains in Southeast Asia, including Vietnam and Malaysia, are also being punished because the United States is aiming to prevent the “laundering,” or transshipment, of Chinese products through third countries to obscure their origin. These rules are being enacted in addition to U.S. export controls on certain dual-use technologies to China, further squeezing Taiwanese firms that have long done business in both the United States and China. In addition, Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia—popular destinations for Taiwanese manufacturers as they diversify their supply chains away from China—face U.S. tariff rates similar to Taiwan’s, making diversification to Southeast Asia less cost-effective.

Facing increasing uncertainty and potential tariffs across the supply chain, Taiwanese firms have significantly ramped up investment in the United States since 2023. The United States is now Taiwan’s largest destination for outbound capital. Increased semiconductor investment in the United States is driving a shift in Taiwan’s outbound investment profile. This year, TSMC announced plans to invest an additional $100 billion, for a total of $165 billion, in the United States, equivalent to 1.8 times the Taiwan government’s entire annual budget. This outflow of capital, talent, and technology fuels concerns that the semiconductor ecosystem in Taiwan will weaken.

Unlike Japan, Taiwan has no formal security or strategic alliance to turn to in Asia, and it is excluded from multilateral trade frameworks. Without formal diplomatic space, Taiwan is unable to join economic groupings like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Taiwan now finds itself navigating a narrowing corridor, boxed in by high geopolitical walls from both Washington and Beijing.

China’s leverage in a reordered region

The U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017 indicated an unwillingness to advance trade liberalization. In 2025, the United States now appears to have abandoned free-trade norms based on nondiscrimination and multilateralism. U.S. tariff policy now frames economic relationships with key partners as zero-sum. Partners like Japan and Taiwan are forced to individually strike highly asymmetrical bilateral deals. The more time trade partners spend managing the U.S. tariff offensive, the less capacity they have to deepen coordination with each other on how to manage challenges in their own neighborhood, such as Chinese overcapacity or overdependence on trade with China. China has been allowed to quietly strengthen its position.

The United States appears determined to reduce China’s economic dominance by building up domestic manufacturing capacity and reducing China’s presence in other economies’ supply chains. The “China plus one” approach by firms to move supply chains into other countries is now less reliable as the rest of Asia is hit by U.S. tariffs. Furthermore, high demand for Chinese imports in other economies, such as Vietnam, limits how much Washington can continue to escalate its trade war with China. As a result, China is faring much better than expected by navigating the United States’ targeted trade measures.

Rebuilding strategy amid uncertainty

Each country in Asia is navigating under high uncertainty, and the pace of change is outstripping the region’s capacity to respond. Because trade deals with the United States are now rushed, transactional, and increasingly made under pressure, countries are signing agreements not out of strategic decisionmaking but to avoid even steeper tariffs. Moreover, the World Trade Organization, with divided membership and consensus-based decisionmaking, may no longer be a viable platform for resolving trade disputes or negotiating global rules. The trade interests of members in the region’s multilateral frameworks, like the CPTPP and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, remain too divided to mount a coherent response to U.S. tariff diplomacy.

As one of us previously wrote for Brookings, Trump’s actions have also led to a loss of trust in advancing cooperation on reducing overdependence on China and strengthening economic security. This means a coalition focused on addressing the trade challenges with China cannot be built while the United States treats its allies as economic rivals. The United States is now less prepared to lead, and U.S. allies are less willing to follow, but the Trump administration’s urges for allies to invest in U.S. manufacturing may further foster supply chain bifurcation. A U.S.-centered supply chain for the American market, to keep pace with the administration’s objectives, might indeed become a reality supported by U.S. allies, while the current China-centric supply chain—linked to Southeast Asia—feeds the Global South.

As confidence wanes in the United States’ ability to continue to steward the global economy, new forms of leadership in the Asia-Pacific are needed, and middle powers like Japan and Taiwan could use this opportunity to cultivate economic and security partnerships—not to confront the United States, but to strengthen their position in managing an increasingly unpredictable ally. If Asian economies aim to regain agency, they must prioritize regional and transregional cooperation, building parallel structures for economic and security resilience.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback, to the CAPRI team for excellent editorial assistance, to Adam Lammon for assisting with the review and publication process, and to Rachel Slattery for web design. Mireya Solís would like to thank Ariqa Herrera for excellent research assistance, and she would like to acknowledge support from the Japan Foundation Indo-Pacific Partnership Research Fellowship.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Asia must prioritize regional cooperation for economic resilience amid tariff uncertainty

As confidence wanes in the United States, new forms of leadership in the Asia-Pacific are needed.

September 8, 2025