Affirmative action is back in the news this year with a major Supreme Court case, Fisher v. Texas. The question before the Court is whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause permits the University of Texas at Austin’s use of race in its undergraduate admissions process. The Court may declare the use of racial preferences in university admissions unconstitutional when it decides the case in the coming months, potentially overturning its decision in the landmark Grutter case decided a decade ago.

Accompanying the general subject of affirmative action in the spotlight is the “mismatch” hypothesis, which posits that minority students are harmed by the very policies designed to help them. Justice Clarence Thomas made this argument in his dissent in the Grutter case: “The Law School tantalizes unprepared students with the promise of a University of Michigan degree and all of the opportunities that it offers. These overmatched students take the bait, only to find that they cannot succeed in the cauldron of competition. And this mismatch crisis is not restricted to elite institutions.”

The mismatch idea is certainly plausible in theory. One would not expect a barely literate high-school dropout to be successful at a selective college; admitting that student to such an institution could cause them to end up deep in debt with no degree. But admissions officers at selective colleges obviously do not use affirmative action to admit just anyone, but rather candidates they think can succeed at their institution.

The mismatch hypothesis is thus an empirical question: have admissions offices systematically overstepped in their zeal to recruit a diverse student body? In other words, are they admitting students who would be better off if they had gone to college elsewhere, or not at all? There is very little high-quality evidence supporting the mismatch hypothesis, especially as it relates to undergraduate admissions—the subject of the current Supreme Court case.

In fact, most of the research on the mismatch question points in the opposite direction. In our 2009 book, William Bowen, Michael McPherson, and I found that students were most likely to graduate by attending the most selective institution that would admit them. This finding held regardless of student characteristics—better or worse prepared, black or white, rich or poor. Most troubling was the fact that many well-prepared students “undermatch” by going to a school that is not demanding enough, and are less likely to graduate as a result. Other prior research has found that disadvantaged students benefit more from attending a higher quality college than their more advantaged peers.

A November 2012 NBER working paper by a team of economists from Duke University comes to the opposite conclusion in finding that California’s Proposition 209, a voter-initiated ban on affirmative action passed in 1996, led to improved “fit” between minority students and colleges in the University of California system, which resulted in improved graduation rates. The authors report a 4.4-percentage-point increase in the graduation rates of minority students after Proposition 209, 20 percent of which they attribute to better matching.

At first glance, these results appear to contradict earlier work on the relationship between institutional selectivity and student outcomes. But the paper’s findings rest on a questionable set of assumptions, and a more straightforward reanalysis of the data used in the paper, which were provided to me by the University of California President’s Office (UCOP), yields findings that are not consistent with the mismatch hypothesis.

First, the NBER paper uses data on the change in outcomes between the three years prior to Prop 209’s passage (1995-1997) and the three years afterward (1998-2000) to estimate the effect of the affirmative action ban on student outcomes. Such an analysis is inappropriate because it cannot account for other changes occurring in California over this time period (other than simple adjustments for changes in student characteristics).

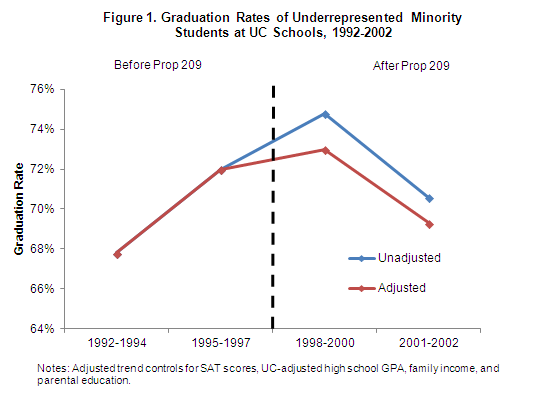

A key problem with the before-and-after method is that it does not take into account pre-existing trends in student outcomes. This is readily apparent in Figure 1, which shows that the graduation rates of underrepresented minority (URM) students increased by about four percentage points between 1992-1994 and 1995-1997, before the affirmative action ban. The change from 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 was smaller, at about three percentage points. The NBER paper interprets this latter change as the causal impact of Prop 209, but this analysis assumes that there would have been no change in the absence of Prop 209. If the prior trend had continued, then graduation rates would have increased another four points—in which case, the effect of Prop 209 was to decrease URM graduation rates by one percentage point.

Adjusting for student characteristics does not change this general pattern. The adjustment makes no difference in the pre-Prop 209 period, but explains about 36 percent of the increase in the immediate post-Prop 209 period (which is consistent with the NBER paper’s finding that changes in student characteristics explain 34-50 percent of the change). But if the 1992-1994 to 1995-1997 adjusted change was four points, and the 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 adjusted change was one point, then Prop 209 might be said to have a negative effect of three percentage points.

None of these alternative analyses of the effect of Prop 209 should be taken too seriously, because it is difficult to accurately estimate a pre-policy trend from only two data points. The bottom line is that there probably isn’t any way to persuasively estimate the effect of Prop 209 using these data. But this analysis shows how misleading it is in this case to only examine the 1995-1997 to 1998-2000 change, while ignoring the prior trend.

Second, the NBER paper finds that less-selective universities produce better outcomes among minority students with weaker academic credentials. This must be the case in order for “mismatch” to exist, but it runs counter to most prior research on the subject. The one exception is a 2002 study by Stacy Dale and Alan Krueger, which found no impact of college selectivity on earnings except among students from low-income families. However, the methodology of the Dale-Krueger study severely limits the relevance of its results for students and policymakers.

In order to control for unobserved student characteristics, Dale-Krueger control for information about the institutions to which students applied and were accepted. This takes into account potentially valuable information that is observable by admissions committees but not the researcher. But it is problematic because it produces results that are based on comparisons between students who attended more or less selective colleges despite being admitted to the same set of institutions. As Caroline Hoxby explains: “since at least 90 percent of students who [were admitted to a similar group of schools] choose the more selective college(s) within it, the strategy generates estimates that rely entirely on the small share of students who make what is a very odd choice.” In other words, the method ignores most of the variation in where students go to college, which results from decisions about where to apply.

The problem with the NBER paper is that it uses a variant of the Dale-Krueger method by controlling for which UC campuses students applied to and were admitted by. And the UCOP data are consistent with Hoxby’s argument: in 1995-1997, 69 percent of URM students attended the most selective UC campus to which they were admitted and 90 percent attended a campus with an average SAT score within 100 points of the most selective campus that admitted them (the corresponding figures for all UC students are 72 and 93 percent).

A more straightforward analysis is to compare the graduation rates of URM students with similar academic preparation and family backgrounds who attended different schools. The mismatch hypothesis predicts that URM students with weak qualifications will be more likely to graduate, on average, from a less selective school than a more selective one.

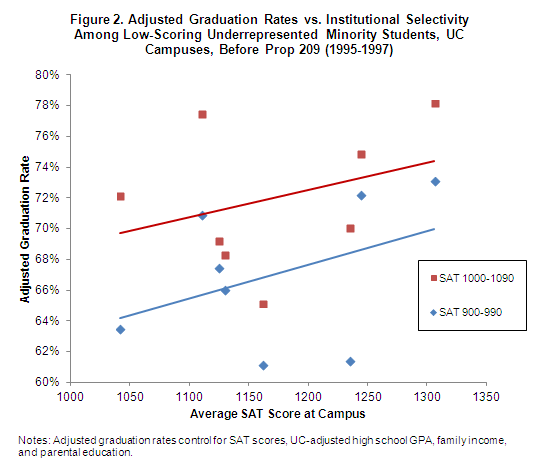

The data show the opposite of what mismatch theory predicts: URM students, including those with less-than-stellar academic credentials, are more likely to graduate from more selective institutions. I calculate graduation rates by individual campus that are adjusted to take into account SAT scores, high school GPA, parental education, and family income.[1] I restrict this analysis to URM students with SAT scores in the 900-990 and 1000-1090 range during the three years before Prop 209, which should be exactly the group and time period when mismatch is most likely to occur.

Figure 2 shows that for both of the low-scoring groups of URM students, graduation rates are higher at more selective institutions. Results for individual institutions vary somewhat, but the upward trend in Figure 2 is clear. I find a similar pattern of results in the period after Prop 209 was passed (not shown). The main limitation of this type of analysis is that it does not take into account unobserved factors such as student motivation that may be associated with admission decisions and student choice of institution. The Dale-Krueger method is meant to address this issue, but for the reasons explained above produces results that are not particularly informative.

A better solution is to find instances of students who attended institutions of differing selectivity for reasons unrelated to their likelihood of success. This is not possible with the UCOP data, but such quasi-experimental methods are used in two other studies that finds a positive relationship between selectivity and student outcomes. In a study published in 2009, Mark Hoekstra used a cutoff in the admissions process at a flagship state university to estimate the impact of attending that university on earnings. This strategy eliminates bias by comparing students who are very similar except that some were just above the cutoff for admission and others were just below. Hoekstra finds that attending the flagship increased earnings by 20 percent for white men.

In a more recent working paper, Sarah Cohodes and Joshua Goodman employed a cutoff-based approach to measure the effect of a Massachusetts scholarship that could only be used at in-state institutions. Students who won the scholarship were more likely to attend a lower quality college, which caused a 40 percent decrease in on-time graduation rates, as well as a decline in the chances of earning a degree at any point within six years.

These two studies do not directly address the mismatch question because they do not focus on the beneficiaries of affirmative action, but they show that taking into account students’ unobserved characteristics leaves intact the positive relationship between selectivity and student outcomes that has been consistently documented in the many prior studies that are less causally persuasive.

To truly put the mismatch theory to rest, rigorous quasi-experimental evidence that focuses on the beneficiaries of preferential admissions policies is needed. But the current weight of the evidence leans strongly against the mismatch hypothesis. Most importantly, not a single credible study has found evidence that students are harmed by attending a more selective college. There may well be reasons to abolish or reform affirmative action policies, but the possibility that they harm the intended beneficiaries should not be among them.

[1] Specifically, I estimate the coefficients on institutional dummy variables after including these control variables. For the controls I include dummy variables corresponding to the categories used in the UCOP data, as well as dummies identifying missing data on each variable so as not to lose any observations. The adjusted graduation rate for each institution is calculated as the difference in its coefficient estimate and Berkeley’s coefficient estimate plus Berkeley’s unadjusted graduation rate for the indicated group of students (i.e. Berkeley’s adjusted and unadjusted graduation rate are thus equal by construction).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).