Imagine the world suddenly had safe and cheap human teleportation. Any group of people, anywhere on Earth, could step into a booth and appear together in the same room a second later. And imagine that when everyone in the room spoke at the exact same time, everyone could understand everything said instantaneously.

It wouldn’t make sense to just bolt this technology onto our existing organizations and institutions. It would force communities of all scales to radically rethink how to assemble and collaborate in work, education, policymaking, and civic life.

For scientists and practitioners dedicated to making shared problem-solving more effective and inclusive within and across policy domains, teleportation via the magic booth would create new possibilities for assembling the right people, at the right moment, around the right problems—and it would demand new norms, incentives, and infrastructures to ensure human agency and societal well-being.

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) does not transport bodies, but it is already starting to disrupt the physics of collective intelligence: How ideas, drafts, data, and perspectives move between people, how much information groups can process, and how quickly they can move from vague hunch to concrete product.

These shifts are thrilling and terrifying. It now feels easy to build thousands of new tools and workflows. Some will increase our capacity to solve problems. Some could transform our public spaces to be more inclusive and less polarizing. Some could also quietly hollow out the cultures, relationships, and institutions upon which our ability to solve problems together depends.

The challenge—and opportunity—for scientists and practitioners is to start testing how AI can advance collective intelligence in real policy domains, and how these mechanisms can be turned into new muscles and immune systems for shared problem-solving.

To grasp the extent of looming transformation, consider how complex policymaking happens today. Scientists and practitioners of collective intelligence in policy domains typically sort into one of two camps.

The first camp starts by booking a room. They obsess over who’s invited, how the agenda flows, what questions unlock candor and prompt insights, and how to help the room move from ideas to practical concerns like “who will do what by when.” Call them the design-minded camp: psychologists, anthropologists, sociologists—collaboration nerds who shape policymaking and action in gatherings spanning town halls to the U.N. General Assembly.

The other group starts by drawing a map. They gather data on actors and variables, draw causal links and feedback loops between them, and embed these structures in simulations. Call them the model-minded camp: economists, epidemiologists, social physicists—complex systems nerds who build tools like energy-economy models (such as POLES) and system-dynamics frameworks (such as MEDEAS) to guide shared decisionmaking for Europe’s transition to a low-carbon economy.

Both domains care about the same big questions: How to coordinate action across many actors and scales to support more sustainable and equitable economies. Both apply serious social science. Yet they mostly work in parallel, with distinct cultures and languages.

Convenings constrained, models ungrounded

Over the past half-century, the design-minded camp has built increasingly sophisticated operating systems for collaboration and shared problem-solving. Early efforts like the RAND Corporation’s Delphi method helped formalize expert elicitation and consensus-building. More recent platforms, such as 17 Rooms, use structured, time-bound convenings to help diverse teams of experts work on specific SDG issues within a larger architecture spanning all 17 SDGs.

From these and related efforts, a playbook has emerged: establish a baseline of shared knowledge across diverse participants, steer discussions toward practical, demand-driven actions; create neutral ground so people can focus on the merits of ideas rather than their institutional talking points; and build enough social glue that participants will commit to concrete follow-through instead of high-level platitudes.

When these processes work, they support shared knowledge, alignment, and real commitments. 17 Rooms, for example, has helped catalyze proposals to scale digital cash transfers for ending extreme poverty, investor tools that surface under-recognized modern slavery risk, and new coalitions for advancing digital public infrastructure. The approach has been replicated in dozens of communities around the world.

But even the best-run rooms hit hard limits. Policy domains are complex systems: Outcomes depend on multiple interacting actors and sectors, across levels from local to global. A room can only hold so many people and perspectives. Most convenings get a few hours or, at best, a couple of days to make sense of the system and plan actions. The result is often what a modeler would call a “local minimum”: a coalition finds a moderately good solution given what they can see, but with limited visibility into system-wide synergies and trade-offs. Smart local actions can end up misaligned with efforts upstream or downstream.

The model-minded camp attacks the same problems from another angle. System-dynamics and agent-based simulations are now staples in climate modeling, macro-financial stability, food systems, and pandemic response.

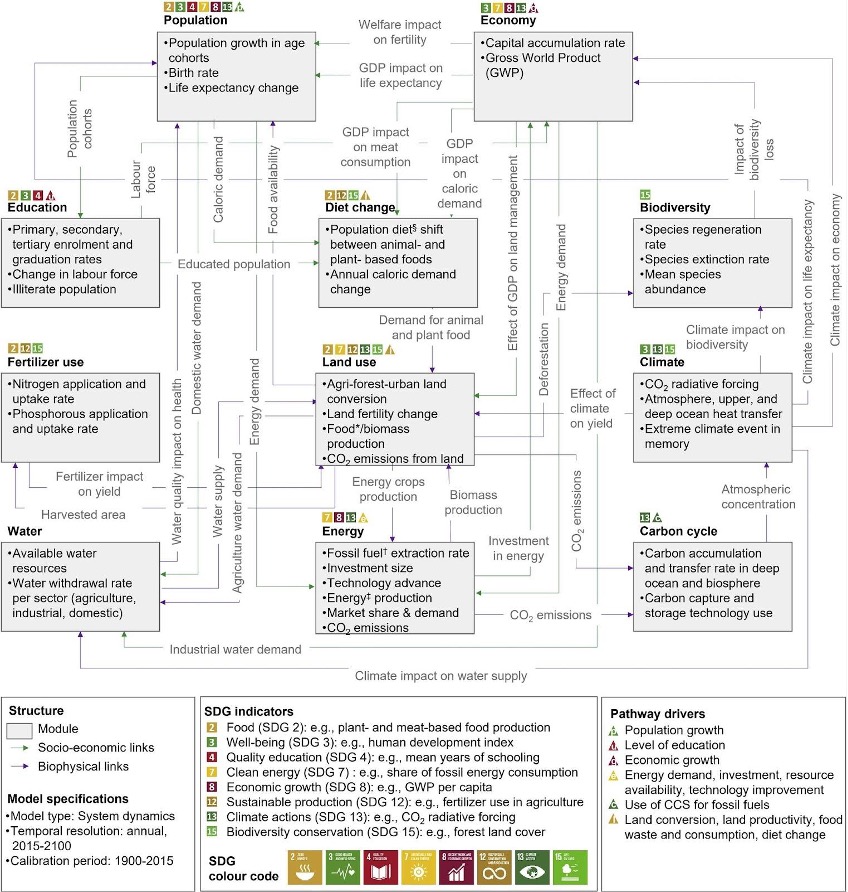

For example, Figure 1 shows a big map for the SDGs based on compartmentalized system dynamics. Such maps capture how values or levels of stocks (boxes) depend upon flows (arrows). Deforestation creates a flow that reduces biodiversity and also changes land use.

They help capture externalities and feedback that no individual team can hold in their heads. They make it possible to stress-test policy packages or see how interventions in one domain—say, deforestation—cascade through biodiversity, land use, livelihoods, and climate risk.

Figure 1. A systems dynamics ‘Big Map’

Source: Moallemi, E. A., Eker, S., Gao, L., et al. (2022). “Early systems change necessary for catalyzing long-term sustainability in a post-2030 agenda” One Earth, 5(7), 792–811, Fig. 2. CC BY 4.0. Model: FeliX system dynamics model (IIASA).

But these tools have blind spots, too. They typically rely on historical, patchy, or centrally curated data rather than live information about what coalitions and institutions are actually doing in specific places. Insights of people on the ground tend to arrive before or in response to real decisions, not in the messy middle where trade-offs are hammered out. And they rarely encode “who needs to do what by when”—the gritty implementation pathways that live in meeting notes, WhatsApp chats, and local political negotiations.

In short: Rooms lack live maps; maps lack street addresses.

Example: Green energy transition

Consider a government debating “big ideas” to accelerate a green energy transition.

A serious proposal will not only reduce emissions. It will also affect growth, equity, social structures, and local cultures. On each of those dimensions, the impacts might be strongly positive, modest, or even negative, and they may look very different across communities.

Our design-minded camp would talk through scenarios, draw on history and local knowledge, and aim for a narrative consensus: Here is roughly what we think will happen, here are the risks, here is who we would need on board. The model-minded camp might produce a probability distribution over outcomes for each community: expected emissions paths, confidence intervals, thresholds beyond which certain interventions fail.

Policymakers are left with a quandary: How do you average a narrative and a probability distribution? How do you combine a story about who needs to do what by when with a graph of potential GDP or emissions paths? The two domains produced complementary but often incompatible forms of intelligence. Recent attempts to integrate them—such as “Participatory Dynamic Systems Modelling”—have been effective but cumbersome.

Enter generative AI

As paradoxical as this may sound, generative AI enables us to use language to do that calculus. Large language models are, at their core, translation engines. They translate across languages, formats, and levels of abstraction. Used carefully, they can also translate across the cultures of rooms and models.

Inside collaborative processes, AI can capture rich, real-time transcripts of discussions; distill arguments, rationales, and assumptions into structured forms; and track who said what, linked to which evidence, with what level of agreement. This makes the tacit more legible.

At Brookings, our early experiments with “vibe teaming” show how this might work in practice. When AI is integrated as core infrastructure rather than a bolt-on tool—an additional teammate that participates in the workflow from the beginning, transcribing, synthesizing, and drafting as people interact with it—it can scaffold better human performance instead of crowding it out. “AI teammate” systems could help trace core ingredients of collective intelligence and human-AI synergy in teams without asking humans to type everything into a spreadsheet. Applying concepts from information theory and complexity, AI could track the “entropy of thought” in real time and even intervene to ensure consensus or compromise at an appropriate rate, neither too fast nor too slow. AI teammates could also double as intermediaries between groups, acting on a team’s behalf to translate learnings, spot synergies, and manage trade-offs between proposed actions within and across relevant policy domains.

On the modelling side, LLMs and their increasingly autonomous (or “agentic”) software extensions make it easier to connect deliberation data directly to maps and simulations. Models can now ingest and organize live signals about which interventions are being attempted where, what coalitions are forming around which options, and what appears to be working—or failing—according to people closest to the problem.

In principle, then, we can imagine a “room+model” learning system. AI-enabled rooms generate structured, contextual data that tunes models and maps. Models and maps then provide timely, understandable decision support back into rooms. Over time, rooms and models could learn from one another.

The design features of these new collaboration and decisionmaking processes are still being worked out. Multiple teams are working in myriad dimensions. Yet they, and we, share a common, straightforward hypothesis: Deliberately designed, AI-enabled room+model processes can drive better problem-solving within and across policy domains.

Now evidence is needed to test that hypothesis. That test will not take the form of a single experiment with fifty trials. Instead, it will be a more agile, collective process of multiple, adaptive heuristic experiments. We believe that progress hinges on answering four core questions:

- Under what conditions does AI in the room actually help people understand a problem domain more deeply, focus on what matters, and reason together about options, rather than distracting, biasing, intimidating, or demotivating collaboration?

- How can the output of those rooms be turned into inputs that update models, so that models reflect what is really being tried on the ground rather than only what is written in strategies and laws?

- What kinds of infrastructure—digital identities, registries, data-sharing and portability protocols (including for model telemetry), evaluations, and governance—are needed so that people are willing to let their words and actions feed into shared tools, confident these will be used to represent their interests and improve decisions, rather than to monitor or control them?

- How do we foster cultures of collaboration and analysis that enable those processes to perform at their best? Can AI-enhanced protocols increase shared knowledge, spur curiosity, and focus attention on shared interests, while building both positivity and skepticism?

From concept to demonstration

Answering these questions will require practical collaborations between modelers, convenors, technologists, and the people whose lives are shaped by policy decisions.

A first demonstration could couple a familiar collaborative format—for example, a 17 Rooms-style process in an SDG domain like food systems or climate action—with an existing modelling effort, such as a system-dynamics platform inside a government or multilateral institution.

One possibility would be the European Commission’s POLYTRoPos initiative, which aims to model place-based innovation and system change in specific territories. Initial findings suggest that aggregate, theory-backed system-dynamics models of policy domains (like industrial transitions or climate change) are feasible, but also that they cannot stand alone. Project contributors have called for participatory system dynamics techniques—demonstrated in public health and ecological management—to co-create scenarios and to surface the granular implementation details that their model, by design, cannot see.

In practice, this might mean co-producing an initial big map of the domain with policy beneficiaries, practitioners, and modelers; instrumenting each room with AI teammates that capture and structure the deliberation; feeding that data into the map and model between sessions; and then bringing a curated set of model-based insights back into the room as prompts, visualizations, and “what if” questions.

It would be possible to explore with participants if or how a room+model process allowed them to see trade-offs earlier, spot synergies they would otherwise miss, and agree faster on workable policies and actions. And if a room+model process helped participants feel more informed, more connected, and more able to act.

Other convenors could adopt and co-develop the same pattern. Multilateral organizations, national governments, and large philanthropies already run high-stakes convenings and fund sophisticated modelling work. Too often, they do so separately. These actors could agree on minimal design elements for every major “systems” initiative, e.g., a repeatable way of bringing people into the room, a shared model or map of the issue, and a light layer of AI to help information flow between the two (including explicit guardrails for how the AI will and will not be used).

Conclusion

As AI rewires the physics of collective intelligence, now is the moment for collaboration nerds, complex systems nerds, and AI nerds to step up together to explore how the future of shared problem-solving can be more dynamic, inclusive, and adaptive to the complexity of our current challenges.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

AI is changing the physics of collective intelligence—how do we respond?

December 16, 2025