The one-minute version of this case study

- The Detroit region’s automotive sector is at a critical technological inflection point. After dominating global automobile production in the early half of the 20th century, the city of Detroit and its surrounding region have faced decades of steep decline. Yet in recent years, the combination of new political leadership, sustained philanthropic investments, and renewed corporate vision—with the “Big Three” automobile manufacturers committing over $6.5 billion to electric vehicle innovation—is creating new growth opportunities for the future of advanced mobility.

- The region’s core challenge—and opportunity—is to emerge from this period of disruptive technological change with a more innovative and resilient advanced mobility sector. The future of mobility will be powered by autonomous technologies and electricity, which is forcing Detroit’s manufacturers to change how vehicles are designed, produced, fueled, and maintained. Navigating that shift requires a workforce with the skills to make and maintain the technologies and products within this “advanced mobility” sector, where Southeast Michigan faces stiff competition from emerging hubs across the southern U.S. and abroad.

- The BBBRC is helping Detroit pursue this industry transformation with intentionality. The Global Epicenter of Mobility (GEM) coalition’s $52 million BBBRC strategy is an attempt to invest in advanced mobility to enhance economic prosperity. GEM seeks to enable Southeast Michigan to diversify and expand its stake in the global market for electric and autonomous vehicles, and in doing so ensure that local workers, entrepreneurs, and suppliers contribute to and benefit from that new growth.

- Evolving a legacy industry requires much more than standalone programs. This case study explores the design and implementation of GEM’s robust mobility cluster transformation strategy, which brings together entrepreneurship, technology innovation and commercialization, support to legacy manufacturers, site readiness, and workforce development. It offers lessons for other regions on how to invest in the collaborative capacity to manage comprehensive economic development strategies that stretch across multiple projects, as well as how to navigate challenges of securing active engagement from industry leaders.

This brief overview of the program provides useful context before reading this case study.

In July 2021, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) launched the $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) through a Notice of Funding Opportunity that outlined a two-phase competition.1 Through its Phase 1 activities, the EDA issued an open call for concept proposals that outlined a high-level vision for a “transformational economic development strategy.” The thesis was that regions would identify an industry cluster opportunity; design “3-8 tightly aligned projects” to support that cluster; build a coalition to “integrate cluster development efforts across a diverse array of communities and stakeholders”; and ensure that these collective efforts advance equity by supporting economically disadvantaged communities.2

In Phase 1, 529 coalitions submitted high-level concept proposals that outlined a vision for the cluster, a high-level description of potential projects, and the key institutions involved in the coalition. After receiving Phase 1 concept proposals, the EDA undertook two months of review to determine which coalitions would be awarded $500,000 technical assistance grants and invited to apply for Phase 2 funding. Those resources enabled a hyper-intensive planning sprint between December 2021 and March 2022. During this period, each of the 60 finalist coalitions expanded their five-page concept proposal into an overview narrative and project proposals that outlined their approach, key assets and institutions, the portfolio of projects and their expected outcomes, and matching resources to complement the EDA grant.

Ultimately, the 60 coalitions submitted funding requests well beyond the BBBRC’s $1 billion allocation. The average Phase 2 funding request submitted to the EDA was approximately $75 million, while the average award amount available in the competition budget was approximately $50 million. Given this gap, in May 2022, all 60 applicants were offered the opportunity to prioritize funding through a budget request reduction process after applications were received. Then, an Investment Review Committee (IRC) assessed all completed applications and made recommendations. In some cases, the EDA ultimately selected a subset of component projects for funding or funded component projects at a reduced level, requiring applicants to modify projects during the award process. In September 2022, the EDA selected 21 of the 60 coalitions for implementation awards, ranging in size from $25 million to $65 million, to be spent over a five-year period.

Background

City and regional context

For over a century, the city of Detroit has been synonymous with the automobile industry. Since the city’s first auto factory opened its doors in 1899 and Henry Ford revolutionized production capacity with the moving assembly line soon after, Detroit has been a global epicenter of automobile production. By the early 20th century, as many as 125 auto companies operated in the city. While the Great Depression hit Detroit’s economy hard, many of the auto factories were repurposed for war production in the early 1940s, with military manufacturing so concentrated in Detroit that it was dubbed the “arsenal of democracy.”

Detroit’s manufacturing boom continued well into the 20th century, leading workers from across the country—including a large Black population migrating from the American South—to flock to Southeast Michigan in search of good jobs at large auto manufacturing companies such as Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors (the “Big Three”). By 1950, Detroit had become the nation’s fourth-largest city and among its most prosperous, anchored around a uniquely strong Black middle class. This in-migration of workers, coupled with increases in productivity driven by technological advancements and the rise of automation, solidified Detroit’s leadership position in global and domestic automotive manufacturing. By 1965, the Big Three accounted for 90% of U.S. vehicle sales.

But the second half of the 20th century was a period of economic and demographic decline for Detroit and the surrounding Southeast Michigan region. By the postwar period, technological transformations had led to consolidation and reduction in the number of auto companies in the region. Multiple interrelated factors contributed to these challenges, but a primary factor was the region’s lack of a diversified economy and its long-standing and deep dependence on an auto industry dominated by a small number of very large manufacturers, each with an outsized influence on the regional economy writ large. Starting with the decentralization of the auto industry in the 1970s, the auto companies began building new factories or moving existing ones—initially to the Detroit suburbs, then other places throughout the Midwest and Sun Belt, and ultimately overseas, where labor and land were cheaper in most cases. Compounded by the 1970s oil embargo—which led to a collapse in demand for large, gas-powered vehicles and popularized smaller, fuel-efficient foreign-made cars—Detroit’s auto industry continued to contract, ultimately leading to the federal government bailout of General Motors and Chrysler (now Stellantis) in 2008.

The city’s population declined by 60% between 1950 and 2010. As jobs left the city and racial tensions increased, middle-class households, which were disproportionately white, moved to the surrounding suburbs. This exodus of jobs and residents had profound socioeconomic implications for Detroit and its region, leaving behind vacant and abandoned property, which precipitated a vicious cycle of decline.

Detroit’s poverty rate increased from 15% in 1970 to over 30% by 2010. With a diminished tax base, the city lacked the funds to support residents or provide services to attract and retain the middle class, thus exacerbating the downward spiral, punctuated by the Great Recession in 2008 and culminating in 2013 with the city of Detroit filing the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. The sharp racial divide between the impoverished, majority-minority central city and its predominantly white, wealthier suburbs is a central challenge that must be addressed for both the city and surrounding region to chart a new era of economic growth.

Resurgence

Contrary to Detroit’s bleak reputation and the national perception of a city in decline, several factors have spurred stabilization and reinvestment in the city over the last few years. A combination of new political leadership, revised corporate vision, and sustained philanthropic investments has catalyzed increased public, private, and nonprofit sector innovation and alignment, even if some efforts remain uncoordinated.

First, new political conditions and leaders in both Detroit and its suburbs are doing business differently with the private sector and have laid the foundation for new cross-regional collaborative partnerships. In the city, strong and stable governance has created more confidence in the city’s future among both business leaders and residents. Mayor Mike Duggan, who has been in office since 2014 and is in his third term, has worked with local business and community leaders to forge an economic vision that has centered on neighborhood investments while simultaneously bolstering the competitiveness of its major industry clusters. As a result, Moody’s raised Detroit’s credit rating in 2022, noting “strong management of challenges” and a “positive outlook.”

Additionally, a new generation of more progressive political leaders in the suburban political jurisdictions across the Detroit region has opened opportunities for cross-jurisdictional collaboration on economic development and targeted efforts to break down racial and economic divides. There is a long way to go to overcome decades of racial division and regional fragmentation, but these represent positive developments in the region’s politics.

Second, the region’s corporate leaders have stepped up to spur new innovation and investment in the mobility sector across the city and region. To ensure Southeast Michigan’s economic resilience in the face of increasing digitalization and automation, the region’s economic and workforce development practitioners have expanded their focus toward mobility technologies that extend beyond traditional automotive manufacturing, including “advanced mobility” technologies such as electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, unmanned vehicles and drones, and robotics. Similarly, the Big Three—concerned about unprecedented global competition in R&D and manufacturing in the mobility sector—are taking steps to innovate in the electric vehicle (EV) and technology arena. For instance, Ford Motor Company, in partnership with Google, is creating an Innovation District in the old Michigan Central Station building; Ford will house some of its R&D functions and create new workforce development opportunities through technical certifications in the district. Meanwhile, Stellantis opened a new factory in the city in 2019 to produce both internal combustion and hybrid models of the Jeep Grand Cherokee. General Motors is investing up to $4 billion to repurpose its Factory ZERO and Orion Assembly plants for the manufacture of new full-size electric pickup trucks. And in a joint investment with LG Energy Solution, General Motors will invest an additional $2.6 billion in Lansing, Mich. for battery cell manufacturing, which will supply EV batteries to Orion Assembly, Factory ZERO, and the company’s other EV plants.

While these investments are significant, they appear to be grounded in Big Three’s old habits of operating independently. Still, new forms of corporate collaboration are emerging, including the 2019 launch of the Detroit Regional Partnership—an intermediary whose mission is to market the Southeast Michigan region to corporations and site selectors. Much of these marketing efforts revolve around the region’s heavy concentration of automotive and legacy manufacturing assets, and embrace automated technology to help other high-tech advanced manufacturing sectors across the economy grow (e.g., robotics).

Finally, philanthropic investments across all domains—workforce and economic development, neighborhood investments, greenways and transportation, etc.—have sustained the region pre- and post-bankruptcy. These philanthropic investments are now coming to fruition, as they are leveraged by the city’s investments in programs such as the Strategic Neighborhood Fund and Motor City Match.

The imperative

In many ways, the efforts outlined above remain fragmented relative to the scale of the technological disruption in Detroit’s auto cluster. There is a perception that the window to evolve the region’s infrastructure, talent, and industrial ecosystem is closing fast. The region’s people—their skills, capabilities, and productivity—will be the most critical determinant in making this transition.

The region’s demographics are shifting. The auto manufacturing workforce—particularly within the supply chain—is aging. Workers and suppliers need reskilling to move into “Industry 4.0” jobs, which require higher familiarity with digital systems, automated machinery, and artificial intelligence. And while new EV plants have brought jobs back to Detroit, this is not in and of itself a sustainable strategy for growth, as the EV supply chain and manufacturing process require less labor than cars powered by internal combustion engines (ICEs). Transition efforts, then, must focus on bringing people into other mobility sector jobs—not just making EVs.

At the same time, Detroit is not simply racing against itself in the EV market. The entire region faces fierce competition for market share in the mobility sector. Chinese auto manufacturers have begun investing heavily in EV manufacturing, and now represent nearly a quarter of the new-car market. Public investment by the Chinese government in this transition as well as the country’s cheaper costs of labor and materials have forced domestic prices lower in an effort to stay competitive—an issue that Stellantis’ CEO has referred to as an “existential problem” for companies that cannot match foreign prices. And while the Big Three continue to operate in Detroit, recent private investments in EV manufacturing and battery production have overwhelmingly flowed into Southern states. Georgia and Tennessee have been steadily catching up to Michigan in the total amount of private sector investment for EV and battery manufacturing that have flowed into the region since the Great Recession.

Even with these global and competitive threats, Southeast Michigan remains one of the world’s densest mobility clusters. As of 2023, it accounted for the majority of the state’s 2,200 supplier and tech center facilities. Preserving this market share will require a two-pronged approach. First, the region must successfully adapt to the electrification and digitalization of the sector, or it risks falling into obsolescence. Second, Detroit must strategize around maintaining—and growing—its dominant role in the domestic and global mobility market. To compete globally, regional leaders understand they must invest regionally in Detroit’s diverse talent, thick supplier base, and entrepreneurial dynamism—and do so in ways that close significant gaps in access to opportunity. Maintaining the region’s leadership in automotive manufacturing and growing its strength in the production of innovative mobility technologies are therefore the imperatives behind the Global Epicenter of Mobility (GEM) BBBRC coalition.

Coalition formation

This section explores how regional intermediaries across Southeast Michigan came together to form the Global Epicenter of Mobility (GEM) coalition. It explains how GEM developed its project portfolio and, in doing so, developed new networks and communication channels between organizations. These outcomes will be relevant for economic developers in other regions with advanced industry clusters, especially those looking to invest in these clusters in ways that benefit historically excluded communities.

Aligning the coalition around a call to action

Despite the maturity and scale of Detroit’s auto industry, the region has not historically benefited from a cooperative ecosystem for economic development in the mobility sector or elsewhere. So, when the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for the BBBRC was announced in 2021, most local leaders knew their region should capitalize on it, but were uncertain which organization was best positioned to lead the effort—and thus were apprehensive about undertaking that role themselves. One thing was clear, though: After decades of fragmented economic development approaches across Southeast Michigan, regional leaders agreed that the BBBRC was a unique opportunity to construct a cohesive, aligned economic strategy.

The dominance of mobility in the Detroit region meant that stakeholders were able to focus on developing a cluster vision, rather than starting the cluster identification process from scratch. After a series of discussions about the NOFO between the region’s economic and workforce development practitioners, this focus on vision-setting led most of them to eventually look to the Detroit Regional Partnership (DRP)—an economic development nonprofit founded in 2019 to promote seven “focus” industries across Southeast Michigan—to serve as the lead BBBRC applicant. Despite being founded to focus primarily on business attraction and not as an organization exclusively serving the mobility sector, partners determined that the DRP’s status as a cluster-focused organization serving the entire 11-county region would give their strategy a competitive advantage with the EDA. Additionally, the DRP had commissioned an analysis of emergent trends and opportunities in advanced mobility, which positioned them to lead an application focused on the sector. These factors led most coalition partners to feel relieved when the DRP agreed to step up as lead applicant—even when it meant adjusting their own strategic visions to align with the coalition.

Despite Detroit being home to the world’s densest mobility supply chain, the complex, multi-layered nature of the cluster made organization leaders unsure whether their partners would have synergistic visions for cluster development (or whether they would want their BBBRC proposal to focus on mobility at all). To bring partners together around an aligned vision at the start of the coalition-building process, the DRP used a quasi-procurement strategy to solicit “requests for proposals” from industry leaders, economic developers, and other partners, in order to identify their needs gaps and industry focuses, as well as gather preliminary ideas for component projects. Results from this initial stakeholder engagement made clear that partners across the region were far more strategically aligned than anticipated; out of the 23 proposals the DRP received, almost all demonstrated a keen interest in leveraging the region’s assets into the future of auto manufacturing, vehicle electrification, transitional infrastructure, and workforce development. As a whole, stakeholders envisioned a cluster strategy designed to help their region corner the market on “mobility of the future” by continuing to support auto manufacturing while simultaneously establishing Southeast Michigan as a powerhouse for advanced manufacturing beyond passenger vehicles. While this vision for cluster transformation continues to be heavily anchored around automotive manufacturing and the transition toward vehicle electrification, its focus also expands to adjacent mobility technologies that support the movement of people, products, and ideas such as drones and eVTOL aircraft manufacturing.

While this strategy for cluster selection ultimately resulted in the proposal receiving buy-in from a broader set of organizations, some stakeholders viewed the process as a double-edged sword. Despite widespread alignment between organizations on what the proposal’s target cluster should be, some proposals that the DRP received during this stakeholder engagement process—and ultimately worked to integrate into the coalition’s BBBRC strategy—were somewhat disconnected and non-synergistic with other elements of the application. As a result, organizations participating in GEM had concerns that this approach led their eventual Phase 2 BBBRC proposal to be more unfocused than it would have been otherwise.

Project identification and selection

Because the timeline for Phase 1 of the BBBRC application process was only three months long, GEM first coalesced around themes instead of concrete project ideas. Once the coalition received their $500,000 Phase 1 planning grant from the EDA, they were able to begin convening working groups every week to hone projects with more specificity for their final Phase 2 application. Project selection within these working groups focused on how to take existing programs and efforts that were already in place and expand on them to extend access to historically excluded populations in downtown Detroit, its surrounding suburbs, and rural communities throughout the region. While these working groups were initially composed mostly of the DRP’s direct membership, project leaders brought in many of their own partners, allowing the coalition’s network of stakeholders to expand exponentially. These working groups developed seven component projects for the coalition’s Phase 2 strategy portfolio, with each project forming its own strategy “pillar”:

- Junction Avenue Site Readiness, led by the city of Detroit, which would transform a vacant property on Detroit’s west side into a mobility-focused industrial space that would integrate regional companies with large original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

- Verified Industrial Properties, led by the Detroit Regional Partnership, which would identify, assess, and ready vacant brownfield and greenfield sites in the DRP’s service region to prepare them for incoming mobility projects.

- Mobility Accelerator Innovation Network, led by TechTown, which would develop a network within Detroit’s entrepreneurship ecosystem to increase the number of mobility startups.

- Testing, Proving, and Demonstration, led by the state of Michigan’s Office of Future Mobility and Electrification (OFME), which would provide support for technology testing and proving in controlled, simulated environments, and allow companies to pilot their new mobility technologies in real-world conditions.

- Company Legacy and Transition Support, led by the University of Michigan’s Economic Growth Institute (EGI), which would help small and medium-sized manufacturers in Southeast Michigan’s automotive supply chain with tech adoption, capacity-building, and product diversification.

- Talent Transformation, led by Southeast Michigan Community Alliance (SEMCA), which would develop business-facing and talent-facing networks to identify employer needs and remove barriers to training opportunities to expand Southeast Michigan’s mobility talent pipeline, particularly among historically excluded communities.

- GEM Central, led by the Southeast Michigan Grants Coalition (a subsidiary of the Detroit Regional Partnership) to convene partners; ensure grant compliance; lead research, storytelling, and DEIJ (diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice) work; and grow the coalition’s network of stakeholders.

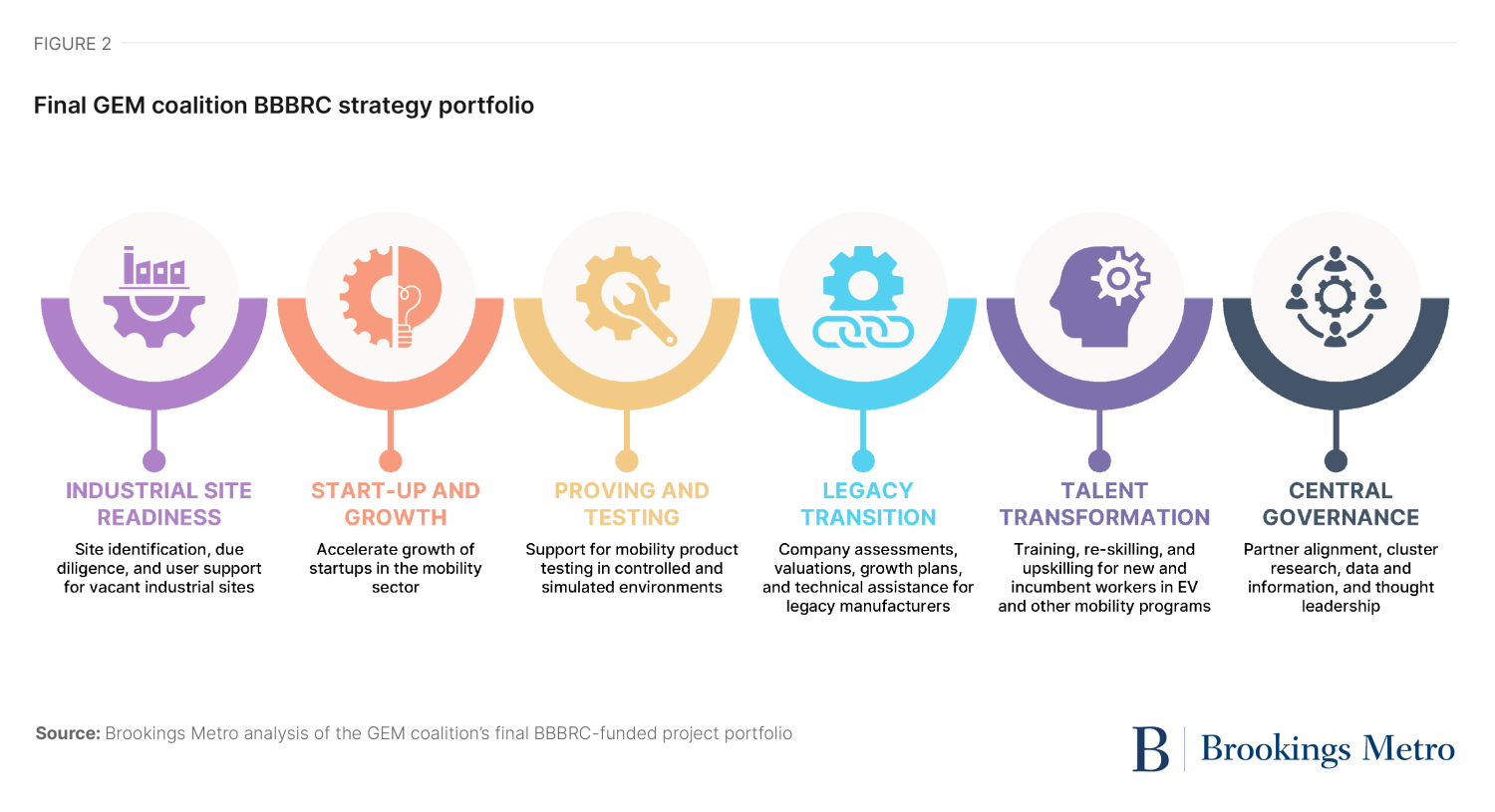

Since Phase 2 funding requests exceeded the BBBRC’s available resources, the EDA gave all Phase 2 finalists, including GEM, the opportunity to reduce their budgets. The group submitted a revised proposal for all seven projects, and ultimately the Investment Review Committee selected six (the Junction Avenue Site Readiness project was not provided implementation funding). Some elements of the remaining six projects did not receive full funding, including proposed wraparound services and community outreach investments. The coalition has since been working with other partners to ensure that these reductions will not hamper its ability to reach underserved populations. However, at the time, leaders felt that these cuts had the potential to make the strategic pillars less transformative for the region’s historically marginalized communities.

The coalition’s final six-project strategy portfolio will fulfill three key objectives:

- First, the coalition will surge investments into the mobility sector’s entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem. To ensure that the Detroit region is able to corner the global market on advanced mobility, one of the coalition’s primary focuses is providing support and encouragement to new mobility startups, which will both bolster their future economic potential and disincentivize them from relocating outside of Detroit. Through this strategy, the coalition hopes to support an array of local entrepreneurs operating across different focus areas of the mobility cluster, including startups focused on EV charging station optimization, home installation of EV infrastructure (e.g., charging stations), drone piloting, and AI-supported vehicle maintenance technologies.

To provide this support and encouragement, GEM has launched the Mobility Accelerator Innovation Network (MAIN), led by TechTown Detroit, to build out the region’s ecosystem of entrepreneurship support providers. Through this network, TechTown will streamline the mobility sector’s concept-to-commercialization processes by linking would-be inventors to funders, private sector supporters, and product licensing resources through a “no wrong door” referral system. As one of the larger, more mature advanced mobility assets in Detroit, TechTown has been involved in the coalition from its inception, helping the DRP bring more technology-focused stakeholders into the coalition, such as Lawrence Technological University’s Centrepolis Accelerator. By the end of their grant period, TechTown and its partners hope to generate a 25% increase in mobility-focused venture capital investments within the state of Michigan, creating over 1,100 new jobs at advanced mobility startups.

In tandem with these efforts, the state of Michigan’s Office of Future Mobility and Electrification (OFME) and NextEnergy will provide mobility startups with access to testing, proving, and demonstration environments, allowing these firms to validate concepts and scale them for commercial application. Though all mobility innovations are required to go through intensive testing and demonstration processes before they can be approved for commercial use, small firms are frequently barred from accessing many of the grant programs and testing assets available to firms that are already bringing in revenue from other products. By removing this barrier, GEM hopes to incentivize mobility startups to scale their projects in Detroit and make entry into the market more accessible for innovators from historically excluded populations.

- Second, the coalition will transition the mobility sector’s small manufacturers and industrial sites to support new growth and extend economic opportunity into historically excluded communities. As of 2023, the state of Michigan hosted over 2,200 supplier and tech center facilities, including 96 of North America’s top automotive suppliers (with most of those suppliers located in the southeastern part of the state, in and around Detroit). While this high level of industry density positions the region well to capture the global market on future-forward mobility, the vast majority of these suppliers serve the internal combustion engine, which constrains total growth potential and puts the region’s mobility supply chain at risk as the transition toward vehicle electrification progresses.

Despite the threat this transition poses, many of the small and medium-sized legacy manufacturers (SMMs) operating in the region have relatively low awareness of how to adopt the technologies that will enable them to service an evolving supply chain, or how to diversify into emerging markets as the mobility sector becomes more advanced. Additionally, many SMM owners are older and ready to retire but have no exit plan. To ensure that the region’s supply chain remains stable through the vehicle electrification transition, SMMs will need assistance in adopting new technologies and diversifying their product lines—an effort that the University of Michigan’s Economic Growth Institute (EGI) has been leading since before the Great Recession. While this initiative far predates the BBBRC, federal funding is enabling the EGI to “get ahead of the transition,” while previously they have provided assistance only after an industry sector has begun to collapse.

At the same time, the DRP hopes to catalyze new economic activity in the region through investments in Southeast Michigan’s industrial infrastructure. Despite the maturity of Detroit’s mobility cluster, the region has a dearth of properties that are site-ready to accommodate and support a large-scale advanced mobility project or site expansion. In response, the DRP will use BBBRC funding to identify, assess, and ready vacant brownfield and greenfield sites across its 11-county service region—improving the likelihood that they will be selected as mega-sites for near-term private sector investments in EV, battery, and advanced mobility manufacturing.

- Third, the coalition hopes to better connect historically excluded communities to job opportunities in advanced mobility, creating more equitable employment and wage outcomes. To lead this “talent transformation” effort, GEM recruited the Southeast Michigan Community Alliance (SEMCA), the Michigan Works! Association agency that provides workforce development programs to residents of Monroe and Wayne counties (excluding the city of Detroit), and an organization known by the DRP’s partners for its “competency and fairness” in administering programs. Though most of SEMCA’s network development and workforce training initiatives predate the BBBRC, this federal grant allows them to operate at a greater scale and improve their ability to grow the mobility talent pipeline in Southeast Michigan’s rural and disconnected communities. This third key GEM objective—focusing explicitly on expanding equity in the workforce arena—is being pursued in conjunction with the equity objectives embedded in the other coalition partners’ programmatic goals, with the aim of compounding the overall equity benefits.

GEM will bring these pillars together through a sixth Central Governance project, which aims to convene the coalition’s partners and drive coalition sustainability through a hub-and-spoke model of governance. Rather than the DRP leading this effort directly, the coalition is being governed by the Southeast Michigan Grants Coalition (SEMGC), a DRP subsidiary that is better equipped to pursue other state and federal funding opportunities in the future.

Centering equity in the strategy-setting phase

While GEM’s primary objective is to fortify Detroit’s mobility industry, stakeholders report that the coalition was formed around a desire to expand economic benefits into the region’s historically excluded communities (HECs). When designing GEM’s project portfolio, coalition leadership aimed to embed equity targets throughout the strategy by customizing how each pillar targets and approaches HECs. For example, the coalition’s legacy transition pillar is taking an equity-driven approach to supply chain services by targeting SMMs owned by members of HECs or operating in HECs, while the coalition’s proving and testing pillar intends to identify communities facing unique mobility challenges (such as disconnection from EV charging infrastructure) and develop solutions targeting those challenges. By adopting this approach, the coalition hopes to better address equity challenges that vary across stakeholders based on their geographic location, race, ethnicity, and role within the cluster.

Yet the long-running disconnect between partners in the region and capacity limitations within smaller, grassroots organizations (which typically have higher levels of trust and credibility with HECs) created significant challenges for the coalition in ensuring that the process for setting this strategy was fully inclusive. One coalition stakeholder referred to the process as a “catch-22,” where small community-based organizations that do not have the capacity to write and orchestrate large federal grants may not be the best candidates for federal funding, but excluding them introduces substantial equity limitations. As a result, the coalition reported struggling to bring small organizations to the table for project selection and strategy formation, though these challenges diminished as GEM’s strategic vision and organizing model solidified—and also as a result of larger intermediary organizations such as TechTown working to identify smaller organizations in their network and include them in the grant as sub-awardees.

Implementing the strategy

Legacy places such as Detroit have been substantially weakened by long-term disinvestment and fragmented sector growth. However, unlike many other legacy regions, Southeast Michigan has also benefitted from substantial philanthropic investments in local and regional intermediaries and strong nonprofit leadership. The BBBRC GEM coalition and its theory of change build on this collection of relatively strong regional intermediaries (e.g., TechTown, EGI, Invest Detroit), as well as newer institutions such as the DRP, to work on a collective vision for addressing discrete pillars of mobility ecosystem development. The early implementation of GEM’s project portfolio demonstrates the significant investment in backbone support and institutional capacity required for executing coalition-based strategies at scale. And while this foundation-setting stage is critical for preparing the coalition for future success, it creates an inherent tension as stakeholders wait for programmatic outcomes to materialize. This stage of implementation also provides critical insights for stakeholders on the importance of embedding community outreach and awareness efforts within strategic processes for them to have maximum impact on the populations they are designed to reach.

Early achievements

While outcomes are still early, GEM’s six projects made notable progress in executing the programmatic elements of their strategies in 2023. Bolstered by their operational successes over the grant’s first year, these outcomes are expected to accelerate significantly in 2024.

- The industrial site readiness pillar, led by the DRP, is deploying $5.6 million in EDA funding toward industrial site identification, assessment, and preparation to ensure that emerging mobility companies have available sites to select from in the Detroit region, and that these corporate in-migrations benefit communities that have historically been excluded from the benefits of industry growth. The DRP has used the BBBRC’s first year for capacity-building, network development, and early program deployment, including: 1) development of a new database of industrial sites across the region to provide data on each site and facilitate engagement with site owners and municipalities; and 2) leveraging the coalition’s $500,000 Phase 1 planning grant to test planned site readiness strategies for due diligence and user support. Project leadership is also developing a new “site education series” for their users on why advanced site planning is necessary and the role of site owners and planning agencies in this process, which they plan to scale over 2024 and 2025.

The DRP has also dedicated significant capacity into building new relationships with the state of Michigan and economic development organizations across the coalition’s service region. After holding “dozens to hundreds” of meetings with these entities, DRP leadership successfully lobbied the Michigan legislature for a new $9.7 million appropriation to the Michigan Economic Development Corporation (MEDC)’s Strategic Site Readiness Program (SSRP). The DRP will use this supplemental funding to conduct desktop and physical site studies to document the strengths and challenges of sites across the region, develop plans to overcome identified challenges, and produce new educational materials to inform prospective mobility companies about the opportunity these sites can provide. SSRP dollars will also help the DRP team add more flexibility to their project’s budget, and address needs that they may not have anticipated when originally building out their strategic plan and budget narrative for the EDA.

- The startup and growth pillar, led by TechTown, is deploying $12.4 million in EDA funding to leverage and strengthen the region’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, ensuring that startup founders have the information and capital access needed to scale their businesses without relocating outside of Southeast Michigan. TechTown has been working with its partners to streamline their ability to effectively work together and simplify the customer journey for the entrepreneurs they are serving. While project leadership eventually hopes to develop a new client relationship management system or resource stacking tool to accurately track and measure progress, they have found that the most efficient way to manage this in the grant’s early stages is through a monthly “pipeline management meeting” with all intermediaries, practitioners, and community partners participating in MAIN. This pipeline management will be further facilitated by the development of a new “asset map,” which will provide TechTown’s partners with a common intake form to ensure that entrepreneurs are referred to the partner best suited to help them meet their next milestone.

While MAIN plans to significantly ramp up programmatic deployment in 2024, the pillar’s early outcomes are still significant, including: 1) creating nearly 70 jobs; 2) growing the Accelerate Blue Fund to over $15 million, a significant increase from 2022; and 3) obtaining 86 patents. Moving forward, TechTown hopes to broaden its outreach to entrepreneurs that have not been connected to the mobility pipeline through new base-level educational programming, including workshops conducted entirely in Spanish. By deploying these programs in the neighborhoods where founders live, project leadership plans to “adapt what our organization already does well and deliver it to people where they are.”

- The proving and testing pillar, led by OFME and its sub-recipient (NextEnergy), is deploying $5 million in EDA funding to provide testing-stage mobility companies with assistance in paying testing site fees—a frequent and significant barrier to entry for these young firms. In 2023, OFME and NextEnergy began accepting grant applications from organizations interested in testing their products at physical testing sites such as Detroit Smart Parking Lab, American Center for Mobility, GM Mobility Research Center, and Mcity.

While the proving and testing pillar has not yet reported tangible programmatic outcomes, the ability for OFME and NextEnergy to begin accepting grant applications is a significant win in itself. Because OFME is a state agency, the project was unable to begin most of their BBBRC-funded work until the Michigan legislature appropriated funding for the project, which occurred in July 2023—over nine months after the EDA awarded BBBRC funding to GEM. As a result, while NextEnergy was able to conduct some site research and other preparatory work on the project in the first half of 2023, OFME was unable to begin hiring or purchasing equipment during this period.

- The legacy transition pillar, led by EGI, is deploying $5.3 million in EDA funding to stand up a new Supply Chain Transformation Center to assist SMMs in diversifying outside of the internal combustion engine supply chain and crafting industry-conscious succession and ownership transition plans. EGI was positioned to launch programmatic implementation earlier than intermediaries in other pillars given the maturity of the program and the high level of capacity offered by the University of Michigan. As a result, EGI received 35 applications from SMMs over the BBBRC’s first year and supported 16 projects across applicants, including evaluating new marketing strategies for industry and product diversification and assessing company-level workforce processes and efficiencies. Each company participating in this program is eligible for up to $100,000 in cost-share funding, depending on EGI’s scoring of their ability and readiness to serve the mobility industry in the future. EGI is working to raise their conversion rate as they progress into the second year of the grant, with the goal of providing assistance to at least 100 companies in total.

- The talent transformation pillar, led by SEMCA, is deploying $16.5 million in EDA funding to provide workforce development support services to mobility sector businesses and workers through consulting, career transition counseling, and targeted training funds. Throughout 2023, SEMCA has been rolling out new educational materials to their vendors and implementing partners to “kickstart enrollment.” Despite staffing delays in the early months of their BBBRC grant, SEMCA and its sub-awardees were able to resolve most of these delays by the end of year one, allowing them to begin designing and executing programs such as: 1) Ann Arbor Spark’s entrepreneur-in-residence program, which connects experienced entrepreneurs with first-time founders and early-stage startups; 2) Michigan Founders Fund’s youth internship program for students from historically excluded communities; and 3) Detroit Future City’s focus group series with workforce development professionals, employers, and students from historically excluded communities, to collect new data on barriers to entry within the advanced mobility talent pipeline.

Over the first year of the grant, SEMCA has also been a blueprint for how workforce-aligned strategies can bolster cross-sector economic development. Leveraging its BBBRC work, SEMCA was able to partner with EGI (the lead organization for GEM’s legacy transition pillar) to participate in the Michigan Defense Resiliency Program, a Department of Defense initiative focused on resiliency and succession planning for mobility companies, energy storage firms, and battery manufacturers. SEMCA has similarly formed new partnerships with state decisionmakers and other regional economic development organizations to integrate traditional workforce resources into broader strategic initiatives, including the Century Foundation’s Industry and Inclusion consortium and Michigan Central’s Tech Hubs proposal.

- Across the coalition, each pillar’s programmatic and administrative successes have been supported by strong leadership from the coalition’s central governance pillar, led by SEMGC and GEM Central (which received $7.3 million in EDA funding). Because GEM is not bound together by a formal memorandum of understanding between SEMGC and the coalition’s other lead intermediaries, GEM Central has governed through a “universal set of operating rules built on mutual trust and awareness between pillars,” fostered by “prioritizing the highest degree of both inter- and intra-pillar collaboration and information sharing.” Over the past year, GEM Central staff have stood up monthly meetings to provide their implementing partners with an opportunity to share updates, discuss their needs, and communicate with peers. This meeting is further complemented by a GEM Central newsletter sent to leadership within each strategy pillar. While organizations in the coalition regularly communicate with each other without relying on GEM Central, coalition leadership has framed these engagement efforts as critical elements to their strategy for “continuous coordination that will show us how our work can be transformational and sustainable.”

GEM Central’s ability to govern a coalition of strong, mature intermediaries required new staff and evaluation systems. Leadership has credited SEMGC’s partnership with America Achieves for assisting with this process by recruiting qualified candidates into leadership roles, while Delivery Associates mapped outcomes and outputs for federal reporting and developed a set of performance deliverables to assess coalition progress on outreach and engagement. This partnership ultimately allowed GEM Central to overcome their early delays in capacity-building and successfully hire a new finance director, chief of staff, and DEIJ officer.

Inputs for coalition-level success

In total, two central themes tie GEM’s successes together coalition-wide. First, many of the successes the coalition has realized over the BBBRC’s first year have been a result of SEMGC leveraging the region’s loose intermediary network to intentionally generate a more collaborative culture across the mobility ecosystem, with “warm handoffs” and a baseline understanding of equity across organizations. Coalition leadership has lauded this culture shift as one of the region’s most significant achievements to date.

It’s so different now than it was last year when no one really knew each other. There are so many good organizations talking with each other that used to operate in silos. Now that our partners aren’t looking over their shoulder to compete for funding with each other, they are finding they all have a shared mission that they didn’t recognize before, and want to become smarter about working together to find ways to move users between different elements of the mobility ecosystem and pipeline. And once you get this group together, it’s hard to tear them apart.

A GEM coalition leader

Coalition members widely consider this new culture of interorganizational collaboration as critical to their work executing projects over the BBBRC’s first year, and in building a “no wrong door” mobility pipeline that supports users across the entire ecosystem. And as the collaborative capacity of Southeast Michigan’s mobility ecosystem has expanded, so too have the opportunities for intermediaries operating within GEM to leverage new partnerships in ways that expand the reach of the mobility ecosystem into adjacent sectors. By finding innovative ways to align GEM’s work with complementary initiatives already in place across the state (even beyond traditional mobility), the coalition is demonstrating how BBBRC funding has facilitated “additive strategy-setting that creates natural outgrowth across and beyond the ecosystem.”

Second, many of GEM’s successes have built upon a high level of investment and commitment to foundation-building across projects. This administrative ramp-up—while time-intensive—has enabled organizations leading each strategy pillar to scale up their institutional capacity, establish new organizational processes, create communication channels, and formalize “accountability loops” across network partners. While many of the intermediaries participating in GEM have relationships with each other that predate the BBBRC, this foundation-building stage has provided the organizations leading each of the coalition’s six strategy pillars with the opportunity to orient their partners within an “unfamiliar and highly formal grant environment,” set expectations, and adjust to new administrative processes where necessary.

Everyone wants to jump into producing work rather than thinking about how to work together, which means you have to do catch-up on the trust-building part. We would have done that even earlier in the process if we could—a four-year relationship is a long one in the nonprofit sector, and things might have gone even more smoothly if we’d already known how to relate to each other with so much money on the table. You know somebody a lot differently once there is this much specificity and money involved.

A GEM project leader

Moving forward, GEM’s success in hiring a new DEIJ officer creates high potential for further equity-driven foundation-building across the coalition in the coming years. While each of the six organizations leading GEM’s strategy pillars have strong institutional commitments to equity, delays in filling this role led to some early fragmentation in the coalition’s ability to develop a central strategy for extending economic opportunity to historically excluded communities (defined by the coalition as “users in the ecosystem with experiences that prevented them from fully participating in high-growth manufacturing, technology, or mobility jobs”). By adding this dedicated capacity around equity, GEM has better positioned itself to improve its tracking of equitable outcomes, implement a new framework for decisionmaking centered around DEIJ, and foster more inclusive coalition-wide governance throughout future grant periods.

This is a very complex system to get our arms around, and inclusion and equity need to be the red thread that connects everything together—it needs to be in front, top, and center if we want sustainable, ecosystem-level change. Right now, we are framing the work of GEM pillars through the lens of DEIJ, and part of that is understanding the mindset of the people doing this work and their perspectives so we can create a North Star about why this work matters beyond traditional output metrics. We just set up a new partnership with Tidal Equality and are leveraging their framework for an ‘equity sequence,’ which helps us ask questions to inform decisionmaking focused on inclusion and equity. We are also standing up GEM Central’s DEIJ workgroup as a holistic accountability partner, so we leave no human behind in this work. We’re looking for more voices from people working inside and outside the ecosystem to help us build new best practices for inclusion and equity for the remainder of the grant and beyond.

Jeannine Gant, DEIJ Officer at GEM Central

Challenges to early implementation

Early implementation inherently involves BBBRC organizations taking time to build organizational capacity, whether that is filling new positions, reskilling existing employees, or extending capacity through new partnerships with other organizations—all while operating simultaneously on the parallel track of launching new programs. Although GEM’s efforts to scale up have been quite successful over the past year and a half, undoubtably there are opportunity costs and “growing pains” associated with this imperative of prioritizing administrative and operational capacity-building in the early stages of implementation. Even as project leadership across GEM’s strategy pillars reports that these capacity-building efforts are strengthening their action plans for implementation in 2024 and 2025, most projects do not have performance outputs or outcomes attached to capacity-building itself—causing many stakeholders to view their work as “behind schedule” due to a lag in short-term programmatic outcomes.

Despite this early-stage conflict between the desire to launch programs quickly and demonstrate early impact on one hand and taking time to methodically scale up on the other, these early scaling efforts are essential in laying a foundation for these organizations to “catch up” and make good on performance outcomes over the next two years, ultimately maximizing impact and meeting program goals in more effective and sustainable ways. Indeed, creating an economic strategy with many partners requires significant up-front administrative capacity to form sub-recipient agreements that provide formal structure to the collaboration while meeting federal requirements around compliance and reporting. Some coalition members have recognized the disconnect between investing in the capacity necessary to achieve long-term impact while also facing pressures to promise—and deliver on—immediate outcomes when seeking funding from external sources such as the EDA.

In the programmatic progress that GEM has made over the past year, many partners have also encountered significant challenges in user awareness about what it means to be a part of the mobility ecosystem. In the coalition’s startup and growth pillar, for instance, TechTown leadership has observed a “knowledge gap” about what it means to be an idea-stage founder (particularly within the mobility cluster), which they believe prevented more founders from participating in either of the two accelerator cohorts they offered over the BBBRC’s first year. SEMCA identified a similar knowledge gap through a needs analysis they conducted in 2023, which demonstrated that job seekers utilizing Michigan Works! Association services have a minimal understanding about what vehicle electrification entails or how the automotive industry is transitioning. At the polar opposite end of the mobility pipeline, EGI has found that many of the legacy manufacturers they serve have low awareness of how the transition from the internal combustion engine to electric-powered vehicles will impact the supply chain they operate in. This knowledge gap has profound implications for the coalition’s ability to reach users from historically excluded communities, which are less likely to exist in traditional information sharing and awareness pipelines.

While less influential on GEM’s programmatic objectives, the coalition has also seen widespread challenges in connecting with the region’s large OEMs, though each strategy pillar has experienced this challenge differently. GEM’s original Phase 2 BBBRC proposal included some strategic alignment with the region’s OEMs through the Junction Avenue Site Readiness project; however, this project was left unfunded by the EDA, and leadership across the coalition’s remaining BBBRC-funded projects report feeling that neither they nor GEM Central have been able to communicate the value of what the coalition is doing for Stellantis, Ford, and General Motors. One coalition stakeholder expressed frustration at the Big Three’s “ambivalence” to early-stage tech, commenting that “you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink. Early-stage commercialization has a very long-term horizon, especially if it includes a partnership with an OEM, and small companies are unlikely to move through that entire continuum.” And while the coalition’s lack of coordination with the Big Three has not resulted in any tangible programmatic delays, coalition members in some pillars have expressed concern that the Big Three’s relationship with organized labor may create animosity toward vehicle electrification and create knock-on effects that impact GEM in the long run. Other partners feel that the Big Three’s apparent disinterest in connecting programmatically with coalition efforts such as GEM will have negative impacts on the coalition’s ability to create long-term, cohesive strategies for cluster development (rather than having nonprofit-led initiatives and corporate-led initiatives operating on parallel tracks), and may reduce their ability to continue to attract funding once the BBBRC is over.

Implications

As the BBBRC enters a more mature stage, GEM should be well positioned to meet its program goals, particularly with the appointment of its DEIJ officer and with the individual coalition organizations concluding the bulk of their scaling up and capacity-building efforts. However, as GEM looks down the road, there are a few areas it should monitor where—at a minimum—greater attention will help it avoid pitfalls that could undermine the coalition’s ultimate effectiveness, and where—at a maximum—greater attention could result in enhanced GEM impact.

First, in general, while increased collaboration among organizations within the ecosystem is a notable positive and a critical GEM “leave-behind” for the region, coalition leadership will want to monitor these advances and consider ways to institutionalize this collaboration, which will put in place structures that enable the sustainability of these new collaborative efforts over the long term. Second, incentivizing connections with parallel private sector economic and workforce development efforts will reinforce GEM’s legacy of collaboration and multiply its economic growth benefits. Finally, while building up GEM’s individual organizational capacities is imperative, this scaling ultimately should not be limited to those organizations within the coalition. If true transformation of historically excluded communities is to occur, the critical organizations serving these areas will need to scale and develop a plan for doing so.

There are three years left in the BBBRC, so it is too early to assess the ultimate success of the program. But GEM’s progress so far provides critical insights for leaders working across economic development, workforce development, and entrepreneurship in other regions where industries are undergoing major disruptions. Three key implications emerge:

- GEM illustrates how flexible challenge grants can enhance a region’s capacity to collaborate on a shared strategy. In a region where a lack of alignment and coordination has previously contributed to economic stagnation, GEM’s early successes stem from its enhanced ability to collaborate, both within individual BBBRC projects and across the coalition. Both within GEM’s federally funded strategy portfolio and beyond, the BBBRC has catalyzed engagement among partners on peer-to-peer learning workshops, initiatives, and grant applications, even beyond the mobility sector. These efforts have enabled other regional intermediaries to leverage the coalition’s efforts and consider where they can plug into elements of GEM’s strategy when developing and scaling economic and workforce development initiatives across the state of Michigan. Other communities may find value in understanding the staff and systems that GEM has utilized to enable this collaboration. Moving forward, a key question for Southeast Michigan’s advanced mobility cluster is whether this collaborative capacity will be sustainable without some external incentive or a catalytic funding resource like the BBBRC continuing to drive collaboration.

- Notwithstanding this improved civic collaboration, GEM illustrates that fully realizing the ambitions of cluster strategies requires corporate engagement. While the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors traditionally lead these types of equitable economic development and systems-building efforts, this one-time injection of large public funds presents an unusual opportunity to leverage greater connectivity with the private sector. This can lead to more sustainable outcomes and intensified, longer-term benefits from GEM’s equitable development and network-building objectives for the region.

Importantly, while the Big Three have not been directly engaged with GEM, this disconnect does not mean that the two groups have divergent priorities. For instance, since 2018, Ford has been converting Michigan Central Station into a “transportation innovation hub” focused on autonomous and electric vehicle businesses—effectively transforming the Corktown neighborhood into an entrepreneurship corridor and recentering the company’s R&D investments back into Detroit. Because the Corktown campus provides space but not services to mobility startups, partners engaged in GEM’s early-stage mobility strategies (such as TechTown) have considered where there may be opportunities for GEM to create new partnerships with Ford around filling these service gaps. These conversations, however, are nascent and have not involved representation from Ford itself. Coalition members have noted similar disconnects between the coalition, General Motors, and Stellantis. There is general agreement that successfully aligning with the Big Three—if not programmatically, then at least strategically—will be critical for the region’s ability to sustain its activities beyond the BBBRC time horizon. Southeast Michigan’s BBBRC strategy illustrates the challenges of securing buy-in from industry leaders as true partners in an economic strategy. In overcoming those challenges, however, GEM also exemplifies how regional leaders can identify specific industry needs and fill those gaps with targeted programming (e.g., TechTown’s services).

- GEM has brought a uniquely broad coalition together, but there are still knowledge and resource gaps that prevent smaller organizations from being fully at the table. As in other regions, gaps in resources and knowledge can serve as significant barriers to entry for smaller, more localized organizations in Southeast Michigan to fully participate in large regional coalitions like GEM. GEM and its leadership should remain acutely aware of finding ways for the coalition to help resource those organizations by offering critical connectivity and support in historically excluded communities. Indeed, GEM’s coalition-building experiences are not uncommon, and there are several important implications for leaders in other regions. First, in a rapidly changing industry like advanced mobility, the information gaps—among entrepreneurs, workers, and SMMs—are significant, and often more pronounced among historically excluded communities. Second, to ensure cluster strategies generate equitable development, coalitions need to address those information gaps through intentional and inclusive outreach, awareness-building, and accessible programing. Community-based organizations are important partners in that work. Third, the organizations with trust and credibility among historically excluded communities may not operate with the resources necessary to navigate federal grants or participate in big regional strategies, which means the onus will often be on a region’s well-resourced actors to extend resources to smaller organizations to address that barrier to entry.

Conclusion

Though GEM’s BBBRC strategy is still being built and will require more corporate buy-in, the collaborative culture it has cultivated has begun to take hold—lending new leadership and life to Southeast Michigan’s advanced mobility sector. Its intentional focus on inclusion and outreach to historically excluded communities will be essential to both individual well-being and regional prosperity. But the coalition will need to identify new funding resources and other strategies if it wants to sustain organizational and regional collaboration as well as connectivity among the different strands of economic regrowth—cultivating entrepreneurship, workforce development, SMM support, and industrial site readiness. It may represent a model, particularly for legacy regions, of how to build partnership networks and communication channels to transition a legacy cluster and leverage inclusive economic growth in the process.

EDA case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publications are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or other scholars.

Brookings recognizes the value it provides in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its funders reflect this commitment.

The authors thank Alex Jones, Bernadette Grafton, Ilana Valinsky, Ryan Zamarripa, Suyog Padgaonkar, Scott Andes, and Justin Tooley from the Economic Development Administration for their insights into the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and for their guidance throughout the development of this case study. For their comments and advice on drafts of this paper, the authors also thank our colleagues Joseph Parilla and Mayu Takeuchi, as well as Christine Roeder, Maureen Donohue Krauss (Detroit Regional Partnership), and Ned Staebler (TechTown Detroit). The authors also thank all local leaders, community-based organizations, economic development practitioners, regional intermediaries, higher education institutions, industry representatives, and other coalition members who participated in informational interviews and site visits throughout this project, and who provided feedback on the research insights and policy recommendations detailed in this report.

This report was prepared by Brookings Metro using federal funds under award ED22HDQ3070081 from the Economic Development Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. The statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Economic Development Administration or the U.S. Department of Commerce.

About Brookings Metro

Brookings Metro collaborates with local leaders to transform original research insights into policy and practical solutions that scale nationally, serving more communities. Our affirmative vision is one in which every community in our nation can be prosperous, just, and resilient, no matter its starting point. To learn more, visit www.brookings.edu/metro.

-

Footnotes

- Economic Development Aministration. “FY 2021 American Rescue Plan Act Build Back Better Regional Challenge Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (ARPA BBBRC NOFO).” U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better https://www.eda.gov/arpa/build-back-better

- Ibid.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).