Since the Kalamazoo Promise in 2005, free college programs—also known as promise programs—have expanded as a popular form of financial aid to address college affordability and access. Promise programs were innovative because their eligibility requirements emphasized geographic location over academic merit and financial need. Students are eligible for promise programs based on where they attend school or where they live. In the last several decades, these programs have multiplied, with over 400 programs currently operating at the state and local levels.

While there is substantial evidence on how promise programs impact students, we do not know as much about how promise programs operate from the perspectives of those who administer the programs. Our recent work fills this gap to offer insights to policymakers. We interviewed 32 college administrators and practitioners from seven community colleges located in California, Florida, Michigan, and New York to understand their experiences interacting with promise students and implementing promise programs. These participants worked directly with students in college units that housed the promise program, and in other support service areas including first-year experience, admissions, financial aid, and academic advising. We analyzed their recommendations and summarized their key points.

1. “Reducing restrictions” to increase “accessibility”

Participants recommended expanding access to more students who would benefit from the promise program. Some programs in our study limited eligibility to full-time students or students enrolling immediately after high school. College administrators expressed a desire to serve more students such as adult students, undocumented students, or formerly incarcerated students and providing more “flexibility and adaptability” in the design of the promise program based on the communities that the college serves. Also, limiting eligibility to the lowest-income students failed to consider affordability for middle or upper-middle income families living in high cost-of-living areas.

In terms of process, one financial aid coordinator wished the programs could be “easy to award, easy to manage,… easy to receive” instead of the current system rife with administrative burden. Researchers have found that administrative burden in promise programs vary substantially across programs. Suggestions to reduce the administrative burden included providing students support with the application process, offering the necessary information that students needed to apply, and allowing students to use the promise scholarship for more terms.

2. “You almost can’t afford to be a student anymore”

College administrators emphasized that promise students had financial concerns beyond just their tuition and fees, including housing, food, transportation, and child care. When these financial concerns were not addressed, promise students often paused their enrollment or dropped out. Administrators recommended multiple approaches to address these barriers: providing additional stipends or partnering with local organizations or nearby colleges to pool resources; distributing aid earlier in the semester so students have greater flexibility to pay expenses upfront; and offering financial literacy courses or workshops so students can navigate the complexities of financial aid. In a randomized control trial with college seniors, a financial education intervention increased students’ financial knowledge and perceived financial self-efficacy, which may influence financial decisions.

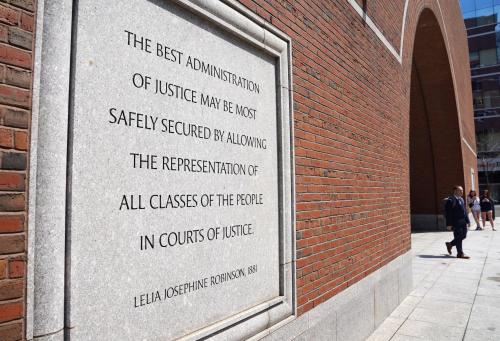

Of note, many administrators said students should avoid taking out loans “if you can help it” because “loan debt is scary.” Even though some students needed loans to stay in college, most participants in our study recommended that students avoid loans and actively counseled students against taking them out. However, this is contrary to a field experiment that found community college students who borrowed to help finance their way through school, on average, earned 3.7 additional credits, raised their GPAs by 0.6 points, and were more likely to transfer to public four-year institutions.

3. “Don’t be cheap if you’re going to do it”

All promise programs in our study were funded by state sources, grants, and private philanthropy. Four programs also received funding from local sources and three programs also received funding from an endowment. However, the funding sources were often unstable and, in some cases, insufficient to meet the growing demand for the program. This uncertainty in budgeting had consequences for the type of services that were offered to students, the staffing levels for the program, and their ability to address their students’ financial needs.

Therefore, administrators recommended that programs commit sufficient resources when funding the promise program and leverage community assets such as local foundations and businesses to support the program. However, these recommendations rely on knowledge of the local context as community-based foundations and businesses may not be sufficiently resourced to provide stable funding.

We also recommend promise programs diversify their funding sources and seek out more stable resources when possible, such as endowments, trusts, perpetual gifts, and tax-incremental financing. However, promise programs need to balance these efforts of creating more sustainable funding sources with their need to secure funding for daily operations.

1. “Direct your student populations to additional resources”

Practitioners highlighted the importance of addressing students’ diverse needs through comprehensive support. Consistent with these recommendations, prior studies across distinct settings demonstrate that offering student supports beyond student aid can significantly increase graduation rates.

Numerous practitioners recommended that other staff members learn about existing supports both on and off campus, such as housing, transportation, child care, supplies, and mental health resources. This awareness would better equip them to connect students to resources and services available to them. At the college level, administrators could offer informational interventions to ensure that all staff members are aware of these college, community, and governmental resources.

Building on the previous recommendation, practitioners also recommended leveraging multiple communication channels to raise student awareness of available resources, including social media, classroom presentations, and course syllabi. These efforts aim to reduce informational barriers, a type of administrative burden that often prevents students from accessing benefits they qualify for and that could help them succeed in college. Last, practitioners recommended engaging directly with students to understand how staff can better support their specific needs.

2. “Be very clear and constant, it’s inescapable advising”

Practitioners underscored the crucial role of persistent and regular advising in helping students navigate college. They recommended more effective advising to students and greater support for advising staff.

One concrete recommendation that emerged from our interviews is for programs to proactively offer advice rather than waiting for students to ask questions. This is important because as practitioners noted, “students don’t know what they don’t know.” As a student support staff member observed, sometimes students learn about critical information (e.g., a GPA requirement to maintain aid) only when “they’re struggling or when it’s too late.” Proactive advising can be achieved via clearer college websites, regular outreach to students, checklists with topics for advisors to cover in advising sessions, and automated alerts to students that leverage university data to warn students when they are in danger of losing program eligibility. Studies show that proactive or “intrusive” advising in promise programs can positively impact retention and degree completion, while also potentially closing achievement gaps for racially minoritized and low-income students.

A second recommendation that could also enable more effective advising is to allow for longer advising sessions rather than the more “transactional” model in which advisors register students and “get them in and get them out” (from an academic advisor). This recommendation aligns with research on authentic “person first” advising relationships. Assigning students the same advisor from their first to second year (similar to K-12) could also help maintain continuity and build stronger relationships. These suggestions hinge on adequate capacity for advising (e.g. lower student-advisor ratios), which remains a challenge for some higher education institutions.

3. “The opportunity to try to build community”

Two practitioners recommended that promise programs foster a greater sense of community through developing a shared identity connected to the program. Research suggests that on average, belonging is associated with student success outcomes, and this association may be stronger for marginalized students.

4. Limited resources challenge advising expansion goals

The above recommendations were often accompanied by an acknowledgment of the resource constraints that hinder more holistic or effective student support. An additional recommendation is to increase investments in student success within promise programs. Prior research shows that adding these supports improves the effectiveness of these programs on post-enrollment outcomes.

Some practitioners noted a disconnect between the incentives for recruitment and those for student success, observing that promise programs often prioritize access, while giving less attention to ensuring students thrive once enrolled. This observation is consistent with existing research on promise programs, which finds consistent positive effects on enrollment but less consistent effects on student success outcomes, including credential attainment.

5. Ensure non-promise students are not harmed

Finally, we offer this caution based on our interviews with program administrators. Institutional resources are sometimes redirected toward promise students, or promise students are granted advantages (e.g., priority registration) over their non-promise peers. Practitioners and policymakers should monitor the effects of promise supports on non-promise students to ensure non-promise students are not unintentionally harmed.

College administrators and practitioners work directly with students day-to-day and have the experience and expertise to offer recommendations for policy and practice. Heeding their feedback will ensure these free college programs live up to their promises.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from the Kresge Foundation (grant no. G-2203-291838) supporting this work.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Administrators push to improve free college access

August 11, 2025