This month marks one year since Congress approved the largest-ever one-time investment in public education: ESSER III, as it’s known, averaged $2,400 per student. This latest round of money left the federal treasury at warp speed, with $80 billion out the door in less than two weeks.

From there, the aid went to state education agencies, where it sat. And sat. And nearly all of it still sits today. Districts were permitted to start spending funds almost immediately, and to submit for reimbursement from their state agencies as they did so.

But most districts still had funding from the prior 2020 aid packages, ESSER I and II. In the end, despite the urgency to get the money to districts, our analysis of federal tracker data indicates that just under 5% of ESSER III was spent as of Jan. 31, 2022—some 10 months after funds were disbursed. (While federal tracking systems can involve a lag, a comparison to a few states’ real-time e-grant systems indicates a delay of only a month or so.)

Districts have been slow to spend ESSER III funds

Some of the sluggish spending is unsurprising given all the demands on district leaders. It takes time to vet proposals, issue contracts, and hire and onboard teachers and counselors who then draw down salaries. Add in the time spent learning the federal rules, engaging with communities, and submitting required plans, and there was suddenly a lot of work to do. For many districts, the administrative workload came at the very moment that leaders were juggling school reopening, labor shortages, ever-evolving health conditions, and more.

And, yes, some of the unspent money has been obligated, meaning districts have initiated facilities projects but not yet paid out on them. And they’ve hired new counselors and will continue to draw on relief funds to pay their salaries each month.

But with a use-it-or-lose-it expiration date of September 2024 for these funds, the math speaks for itself: To spend the remaining funds, most districts need to up the pace at which money goes out the door each month.

Lower spending to date means a larger cliff later

In Figure 1, we model what would be a smooth drawdown on each of the three waves of ESSER given that each has a different start and expiration date. To be on track, we should now expect about $12 billion in expenditures per quarter, or just over $4 billion per month. (In practice, rather than layer the funds, districts tend to sequence them using ESSER I first, then ESSER II, etc.)

At the start of 2022, districts were behind on this spending plan. The most recently tracked month shows $2.5 billion in spending for January—far short of the $4 billion monthly spending laid out in the model. Cumulatively, only $33 billion of the model’s projected $47 billion has been spent thus far. Slower spending now means that districts will need to spend even more than the $12 billion per quarter going forward if they want to spend it before the deadline. That also means that the new higher monthly spending levels will be followed by an even steeper fiscal cliff if, as currently planned, the money abruptly ends in September 2024.

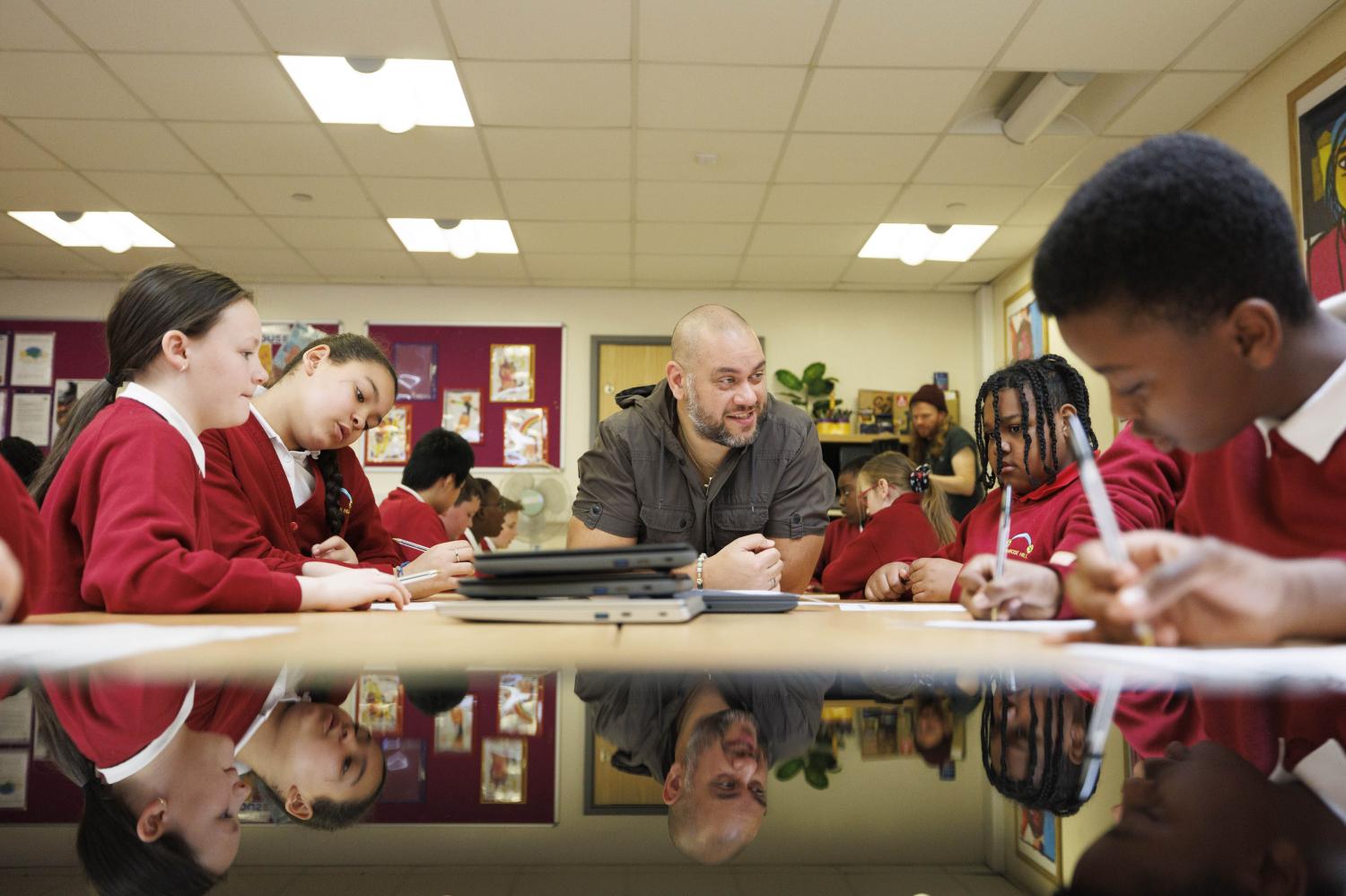

Districts decide how to spend and how quickly to spend

The law gives districts wide latitude and few restrictions, and thus choices are all over the map. One district awards sizable staff bonuses, another remodels a building, and another hires an army of counselors, nurses, and social workers. Some are launching tutoring efforts, while others are investing in professional development or refreshing their curriculum and technology. Atlanta added 30 minutes to the school day and Boston is running summer recovery courses for teens. Some are doing a bit of everything.

In many regions, the flurry of spending has triggered a corresponding flurry of hiring. Districts are competing for a limited labor pool, and using signing bonuses, retention pay, and other strategies to expand labor rolls to a new and higher level than ever before.

In contrast, some big, urban districts, including those in Minneapolis, Sacramento, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, are using funds to backfill budget gaps (some caused by pre-pandemic overspending or enrollment losses). Instead of launching new programs and hiring new staff, the funds are paying the salaries of staff who’ve been in these districts for years.

In the end, there simply is no “typical” spending profile.

Transparency around federal recovery spending remains a challenge

Here’s something that is typical. Note that we’re talking about actual spending, not data from the plans that districts were required to draft in summer 2021 before labor shortages got in the way of hiring and inflation fueled demands for pay hikes. They’re not the same. Actual spending can and is straying far from the original plans.

There are some efforts to capture spending: 20 states now have public-facing systems tracking district ESSER reimbursement requests. But, for now, many will find the data on how the money is spent unsatisfying.

Take California, for example. Per the American Rescue Plan, districts must spend 20% of ESSER III to address lost learning time. When requesting reimbursement, California’s Department of Education requires districts to report which (if any) strategy the district used. For the $56 million spent so far to address learning loss in California districts, Figure 2 shows that very little of the early spending is on adding hours to the school day, year, or summer. Rather, 78% is simply labeled “other.”

Similarly, Washington state tracks various spending categories for the less restrictive 80% of funds, asking districts to select from categories like sanitization, mental health, and technology. Here again, as evidenced in Figure 3, most of the money gets coded in an “other” category that yields little valuable information.

Similarly, Washington state tracks various spending categories for the less restrictive 80% of funds, asking districts to select from categories like sanitization, mental health, and technology. Here again, as evidenced in Figure 3, most of the money gets coded in an “other” category that yields little valuable information.

None of this is to say that money wasn’t needed. As each month goes by, it becomes increasingly clear that many students lost ground on their academics during the pandemic and that they need focused investments to catch up. Reports can now quantify how much students have fallen behind in math and reading, revealing even worse outcomes for those who are poor and nonwhite. There’s simply no way districts could meet these challenges without added resources.

The most important question: Is the historic investment “working”?

Clearly, the stakes are high. With loads of money and an expiration date approaching, districts need to stay focused to make sure investments are having their intended effect: ensuring that kids are making progress on reading, getting up to speed in math, and staying on track to graduate. Where investments aren’t effective, districts should be pivoting to redirect funds accordingly—and doing so ASAP.

But one year in, it’s clear that we don’t have data systems in place to answer the “Is it working?” question in any timely or useful way. The answer doesn’t come from measuring how money is spent. Rather, knowing whether investments are working requires regularly tracking student measures to see whether schools and classrooms are making gains, and for which kids.

In most states, existing data systems are nowhere close to offering these answers. Federally required annual testing was scrapped in 2020 and inconclusive in 2021. That leaves most districts lacking any sort of post-pandemic baseline from which they could measure month-to-month progress. And of course, we’re not exactly measuring month-to-month progress either.

Any progress data that does exist is gathered by individual districts of their own accord, with consequent variety in approaches and priorities. One district launches attendance efforts and obsessively tracks its chronically absent students to see if it is making progress. One district partners with a tutoring vendor that regularly measures student reading. And yet, another simply admits that academics isn’t a priority right now.

All told, this means we’re counting on leaders in thousands of districts to figure this out on the fly—and fast. And they’re expected to do so with no established data systems that could point the way. Some district investments will put student learning back on track and others won’t. Only in a few years will we have any indication of which districts did what and whether it worked.

In that sense, the American Rescue Plan’s strategy might be best described as: fund and pray.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).