On Wednesday, June 8, the Brown Center is hosting a public event about racial inequities in education. An esteemed group of community leaders and education experts will gather to discuss how race and income level factor into education opportunities in present-day America, and why, in an age when the national dialogue routinely does focus on issues of racial inequality, isn’t education a bigger part of that conversation?

In advance of the event, we’ve put together a list of seven findings about racial disparities in education that scholars and contributors at the Brookings Institution have highlighted over the past year.

School readiness gaps are improving, except for black kids

As Richard Reeves details, a 2015 paper by Sean Reardon and Ximena Portilla demonstrates that inequality in school readiness—in terms of math, reading, and behavior—declined quite significantly between 1998 and 2010, but that progress in terms of closing race gaps was uneven. While Hispanic-white differentials in school readiness have narrowed, the black-white gap has shown much less movement, and that movement is not statistically distinguishable from zero.

Misbehavior in school can pay off for white, but not black students

On the Chalkboard, Nicholas Papageorge summarizes his research that finds some non-cognitive skills that manifest as childhood misbehavior in the classroom, such as aggression, are also predictive of higher earnings later in life. He finds, however, that this benefit is limited to children who do not come from low-income families. And preliminary evidence shows that for the same levels of externalizing behaviors, African American children face higher earnings penalties than white children.

Teacher-student racial mismatch harms black kids

Seth Gershenson’s troubling research finds that non-black teachers have significantly lower educational expectations for black students than black teachers do when evaluating the same students. For example, when a black student is evaluated by one black teacher and by one non-black teacher, the non-black teacher is about 30 percent less likely to expect that the student will complete a four-year college degree than the black teacher.

In another Chalkboard post, Dick Startz discusses Adam Wright’s findings that black and white teachers also evaluate the behavior of black students differently. When a black student has a black teacher that teacher is much, much less likely to see behavioral problems than when the same black student has a white teacher. This has serious and far-reaching implications. For instance, the research demonstrates that the more times a black student is matched with a black teacher, the less likely that student is to be suspended.

White and Asian students are more likely to be exposed to advanced classes

The practice of tracking—offering qualified students the opportunity to take advanced-level courses apart from many of their fellow students—is more prevalent in suburban middle class communities and in schools serving white and Asian students and less prevalent in urban schools and schools serving predominantly black, Hispanic, or disadvantaged populations. A historical belief that tracking itself is discriminatory in nature has led different communities to view and utilize the practice in unequal measure, according to Tom Loveless. And as a result, disadvantaged students are much less likely to be exposed to and to benefit from advanced coursework.

Gaps remain in high school completion rates

While the gap in high school completion is closing, black and Hispanic students are still less likely than their white counterparts to have a high school diploma, according to a paper on multidimensional poverty and race by Richard Reeves, Edward Rodrigue, and Elizabeth Kneebone.

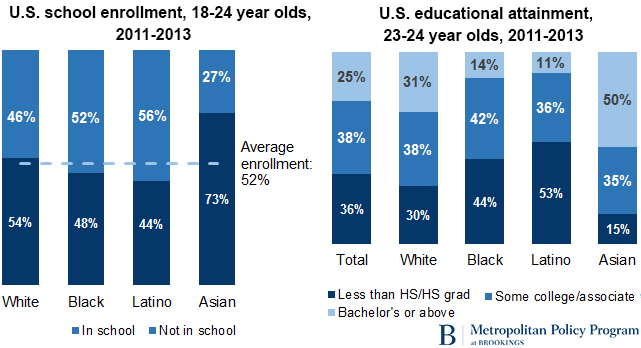

Similar college enrollment rates mask unequal degree completion rates

Black and Latino students have only somewhat lower rates of post-secondary school enrollment than whites and Asians, but have much lower levels of educational attainment by their mid-20s, according to the Metropolitan Policy Program’s Martha Ross. While students across these groups enroll at similar rates, they earn bachelor’s degrees at significantly different rates:

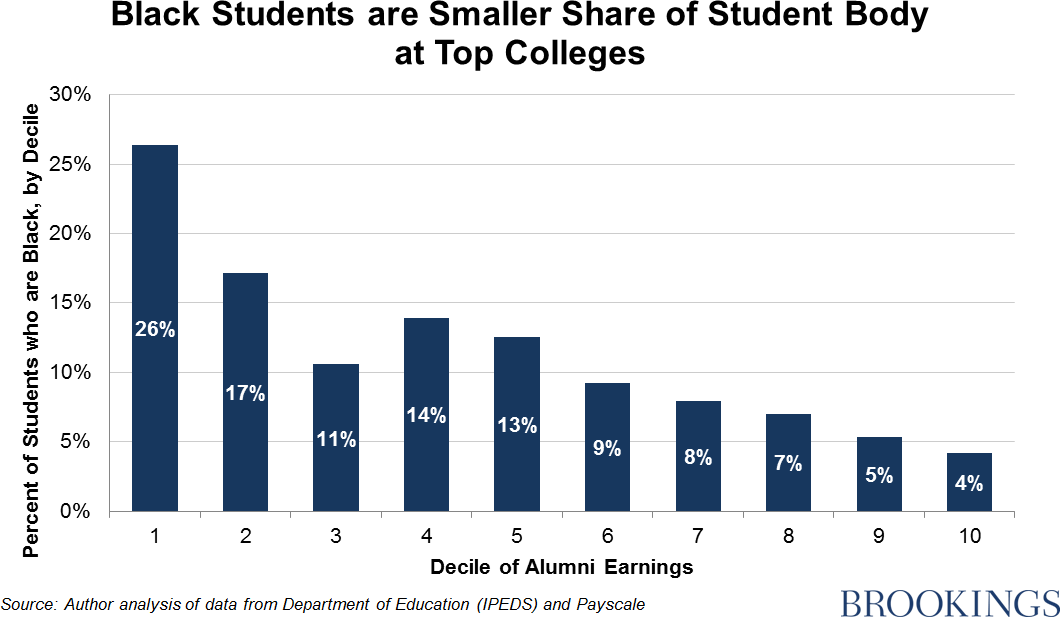

Black and white students do not attend colleges of equal quality

While there has been an increase in black college-going, most of this rise has been in lower-quality institutions, at least in terms of alumni earnings, illustrates Jonathan Rothwell. Black students make up just four percent of undergraduate enrollees in the top decile of the nation’s four-year colleges, ranked by mid-career alumni earning figures. By contrast, 26 percent of students in the bottom rank of colleges are black:

These facts demonstrate what any number of Americans could tell you: there are significant racial disparities in terms of education access and quality in the US. Join us on June 8—online or in-person—as we discuss how to elevate this issue to the forefront of the political discussion this election year and other ways to address this fundamental problem. You can follow the conversation on Twitter with #EducationDisparities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).