On June 1, 2012, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy signed legislation that legalized medical marijuana. Passage of the law set into a motion a multi-year process in which legal, regulatory, and commercial systems were designed and implemented, producing one of the most heavily regulated, complete medical marijuana systems in the United States.

Connecticut was not the first state to grant its residents access to medicinal cannabis, but it put in place a program that was, in many ways, unique among its peers. Connecticut treated medicinal marijuana like…medicine. It is true other states engage medical communities and enact standards that adhere to medical and scientific rigor, but in Connecticut that approach is holistic and comprehensive. The result is a system that its regulators proudly believe is safe, effective, tightly controlled and is helping patients in the Nutmeg State every day.

This month I had occasion to sit down with four state employees who serve as the regulatory brain trust behind Connecticut’s medical marijuana program. All four hailed from the state agency with regulatory jurisdiction over marijuana, the Department of Consumer Protection. They included the Deputy Commissioner, the Director of the Drug Control Program, the Medical Marijuana Program Manager, and the Department’s Legal Director. Each worked closely on the program’s development, implementation, and ongoing administration, and each offered substantial insight into how the program works, and why specific choices were made in its design.

What I found was a medical marijuana program driven not so much by grassroots advocacy and market energy, but by medical and pharmaceutical concerns about this not-so-new product. Many of the same concerns, rules, systems, and approaches that the state applies to the regulation of other pharmaceuticals were applied to the regulation of medical marijuana. Such an approach may seem intuitive in the regulation of a medical product, but many other states have embraced dramatically different regulatory models for their medical marijuana programs.

So, how has medical science and pharmaceutical knowledge driven the medical marijuana system in Connecticut? A variety of the system’s features reflect this motivation.

First, the system is being implemented by the Department of Consumer Protection (DCP)—the state agency already charged with regulating pharmaceuticals. In fact, the medical marijuana program falls within the state’s Drug Control Division, offering the existing institution’s staff and expertise to this new area of public policy. The division’s chief is a licensed pharmacist, and he explained the division’s enforcement agents have pharmaceutical backgrounds. Relying on DCP’s jurisdiction allowed the state to avoid reinventing the regulatory wheel and capitalize on a broad base of knowledge. It also ensured that regulators approached medical marijuana from a medical and pharmaceutical perspective, rather than a tax generator or a mislabeled vice.

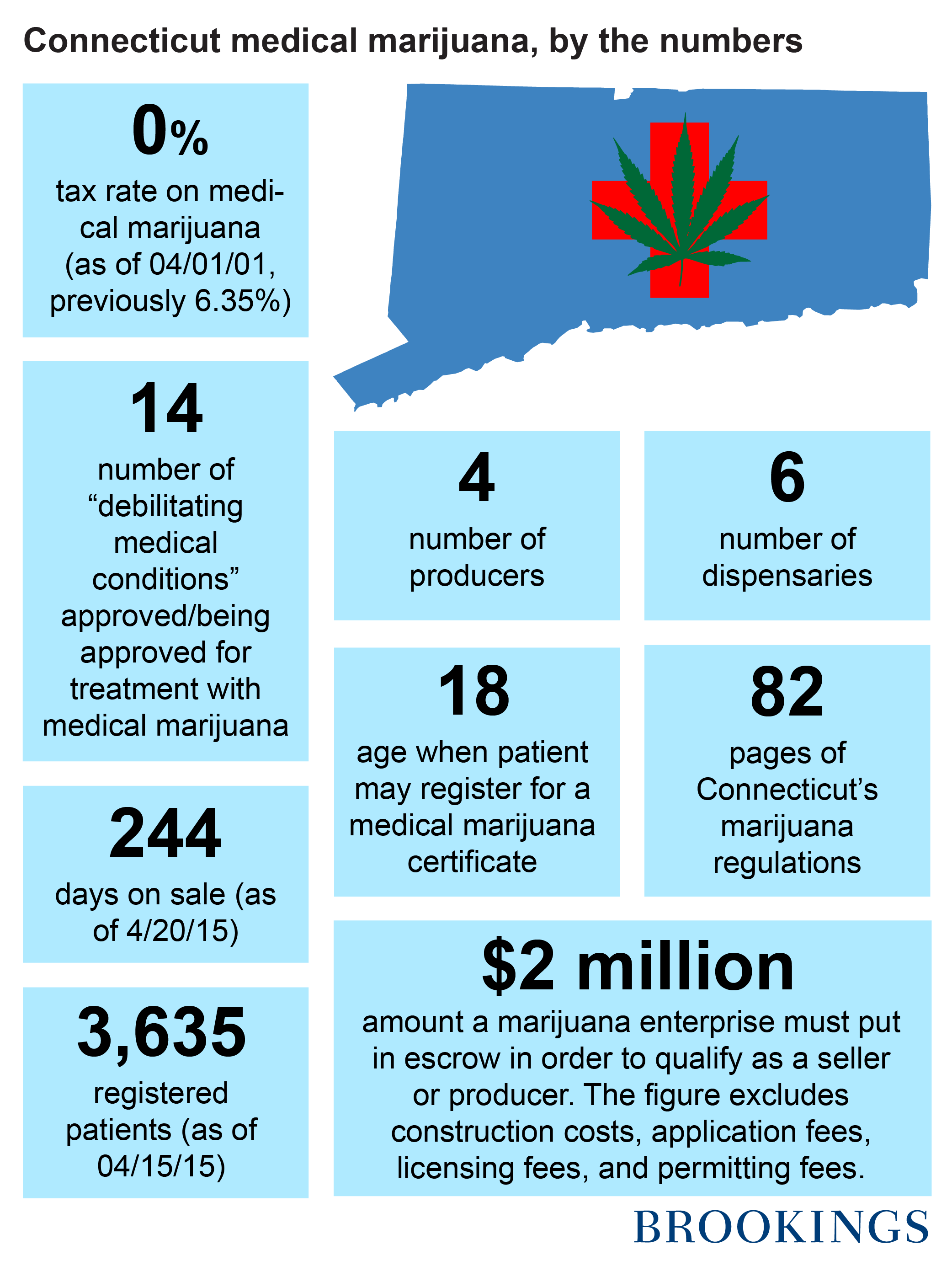

Second, Connecticut’s medical marijuana dispensaries function more like pharmacies than other states’ medical dispensaries. Products have clear, technical, medical labeling describing its contents and chemical composition (with regard to THC, CBD and their sub-types). In addition, a board certified pharmacist is required to dispense medical marijuana at each of the state’s six licensed marijuana dispensaries. The patient experience is intended to be clinical, as the purchase of any other pharmaceutical would be.

Third, the law authorizing medical marijuana called for the rescheduling of cannabis from a Schedule I to a Schedule II drug in Connecticut (formally from C-I to C-II). There is some rhetorical importance to rescheduling. The change declares cannabis to have “a high abuse risk, but also have safe and accepted medical uses.” However, in Connecticut, there is more to the story. Rescheduling makes cannabis eligible to be included in the Connecticut Prescription Monitoring and Reporting System, a statewide database updated weekly with patient-level prescription data. The DCP’s website explains that the system can “be used by providers and pharmacists in the active treatment of their patients. The purpose of the (system) is to present a complete picture of a patient’s controlled substance use, including prescriptions by other providers, so that the provider can properly manage the patient’s treatment, including the referral of a patient to services offering treatment for drug abuse or addiction when appropriate.” Under rescheduling, medical marijuana is part of this system and becomes part of patients’ holistic treatment plan. It also allows for comprehensive data on how marijuana affects symptoms and conditions as well as its interaction with other substances. The system is scientific, medically responsible and will be extraordinarily useful in the study of the medicinal benefits of cannabis.

Fourth, the original law authorized medical marijuana for the treatment of eleven debilitating medical conditions. They included: “cancer, glaucoma, positive status for human immunodeficiency virus or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, damage to the nervous tissue of the spinal cord with objective neurological indication of intractable spasticity, epilepsy, cachexia, wasting syndrome, Crohn’s disease, posttraumatic stress disorder.”

However, the law allowed flexibility and encouraged the medical community to help determine qualifying conditions. For that purpose it authorized the Medical Marijuana Board of Physicians, composed of four Connecticut board certified doctors and the Commissioner of Consumer Protection. This body is charged with entertaining petitions for additional qualifying conditions, among other duties. The board holds public hearings and entertains testimony from physicians, researchers, patients, advocacy organization and opponents in an effort to let medical data and information guide their decision.

The DCP regulators described the board as an effective institution, driven by science and medicine. It is clear from watching these hearings that the members of the board are not simply “yes-men” readily expanding the medical marijuana program. They take their role quite seriously and while they have recommended expanding qualifying conditions to include sickle cell anemia, post-laminectomy syndrome (a spinal disorder), and psoriatic arthritis, not all votes are unanimous. The votes on sickle cell anemia and psoriatic arthritis each had one no vote, and the proposal to include Tourette’s syndrome as a qualifying condition was unanimously rejected. The board works hard to make sure that medicine and science, not emotion, drive change in the medical marijuana program.

Fifth, DCP regulators spoke with pride about the dosing and testing procedures in the state. The stated goal was to ensure that the patient understood the precise chemical composition of their product—in much the same way they would for a narcotic painkiller or an anti-anxiety medication. DCP and marijuana producers rely on state certified control substance testing labs to examine every strain, edible, vape oil compound, and other tinctures that are sold in Connecticut. The testing examines not just the composition of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabinoids (CBD), but also for contaminants like mold, pesticide, etc. The laboratory testing also requires that labels include information to facilitate accurate dosing among patients. The head of the state drug control division was clear: their goal was to make medical marijuana as safe, accurate, clean, and predictable as any pharmaceutical sold in Connecticut. Relying on existing laboratories and promoting the same types of safeguards and quality controls the state demands for mainstream pharmaceuticals made medical marijuana testing a bit easier to implement than an approach invented from whole cloth.

Finally, any medical, science-driven public policy would have to be inclusive of patient needs and rights. DCP regulators noted that in advance of marijuana producers and dispensaries being approved and product coming to market, the state developed a patient registration program so that patients would be prepared to access medical marijuana as soon as possible. Michelle Seagull, the Deputy Commissioner of Consumer Protection noted that the goal was “creating an online registration system without undue burden on patients.” That required balancing the state need for patient information with a patient desire to avoid unnecessary bureaucratic red tape.

Patients have access to substantial amounts of information about the medical marijuana program on the DCP website. John Gadea, the Drug Control Division chief also noted that the Department provides, “continuing education on a variety of topics, including medical marijuana” to the medical community. That effort facilitates patient access by expanding physician knowledge.

Tax policy also illustrates Connecticut’s responsiveness to patient need and the treatment of medical marijuana like a pharmaceutical. Originally, medical marijuana was subject only to the state’s standard sales tax (6.35%), avoiding any special marijuana taxes. However, effective April 1, 2015, medical marijuana is exempt from state sales tax—just like other prescription drugs in the state. This move reflects both a willingness to treat medical marijuana users like all other medical patients.

In sum, Connecticut made clear choices about what its medical marijuana program should look like, and many of those choices reflect medical and pharmaceutical policy in that state. Much of the criticism of medical marijuana stems from states and policies that treat the product very differently than mainstream medicine. In some states, the medical marijuana system is merely seen as a gray market that allows marijuana access to both legitimate patients and those seeking marijuana for recreational purposes. The breadth and depth of the regulatory apparatus in Connecticut (more on that in another blog post appearing tomorrow) cannot possibly prevent all gray market activity, but it offers tremendous safeguards against it, particularly when compared to some other medical marijuana states.

Some concerns naturally emerge from a system as heavily regulated as Connecticut’s. Does the regulatory environment drive up production prices in ways that incentivize patients to rely on the illegal market for affordable access to marijuana to treat their symptoms? Surely the state’s tax policy helps deal with that in part, but it is a critical empirical question that public opinion polling and other analyses like demand studies can help answer. Next, does the regulatory environment create burdens to access that mean some patients, who would be legitimately served by medical marijuana, are unable to access the market? The science-driven approach embodied in the deliberations of the Board of Physicians should help guard against such patient barriers. It can also play a role in investigating or explore such patient concerns and recommending changes to the Commissioner of Public Safety and/or the legislature.

Connecticut is one model for what a medical marijuana system can look like. In many ways, it differs from other states that allow a regulated, market-based system of medical marijuana access, and states considering approving medical marijuana or reforming their existing systems can look to the state as one that favors heavy regulation as a means of ensuring quality, safety, security, and patient (consumer) protection.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

4/20 series: Medical cannabis in Connecticut driven by science and medicine

April 21, 2015