Since the fall of the USSR, Ukraine has been struggling to build an independent and democratic nation. Chrystia Freeland explains this struggle in the latest Brookings Essay, “My Ukraine: A personal reflection on a nation’s dream of independence and the nightmare Vladimir Putin has visited upon it.”

Here are 10 maps from her essay that explain the political events in Ukraine since it gained independence in 1991:

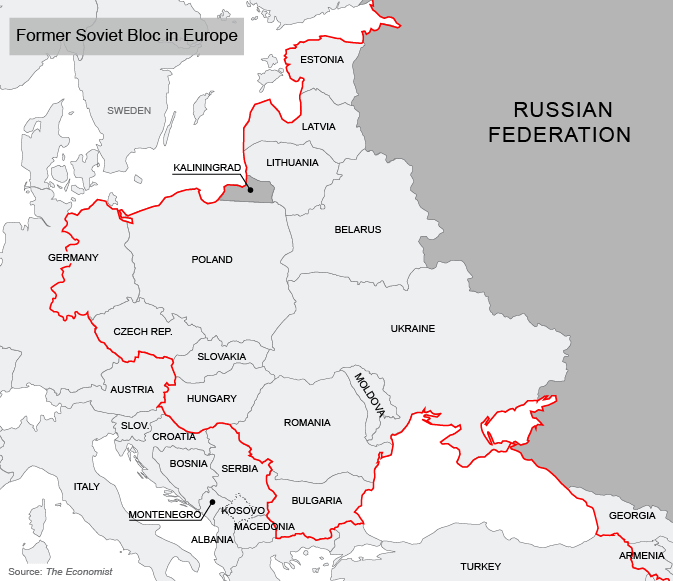

Ukraine was at the heart of the Soviet Bloc

Ukraine was part of the USSR from its inception in 1922 until its collapse in 1991.

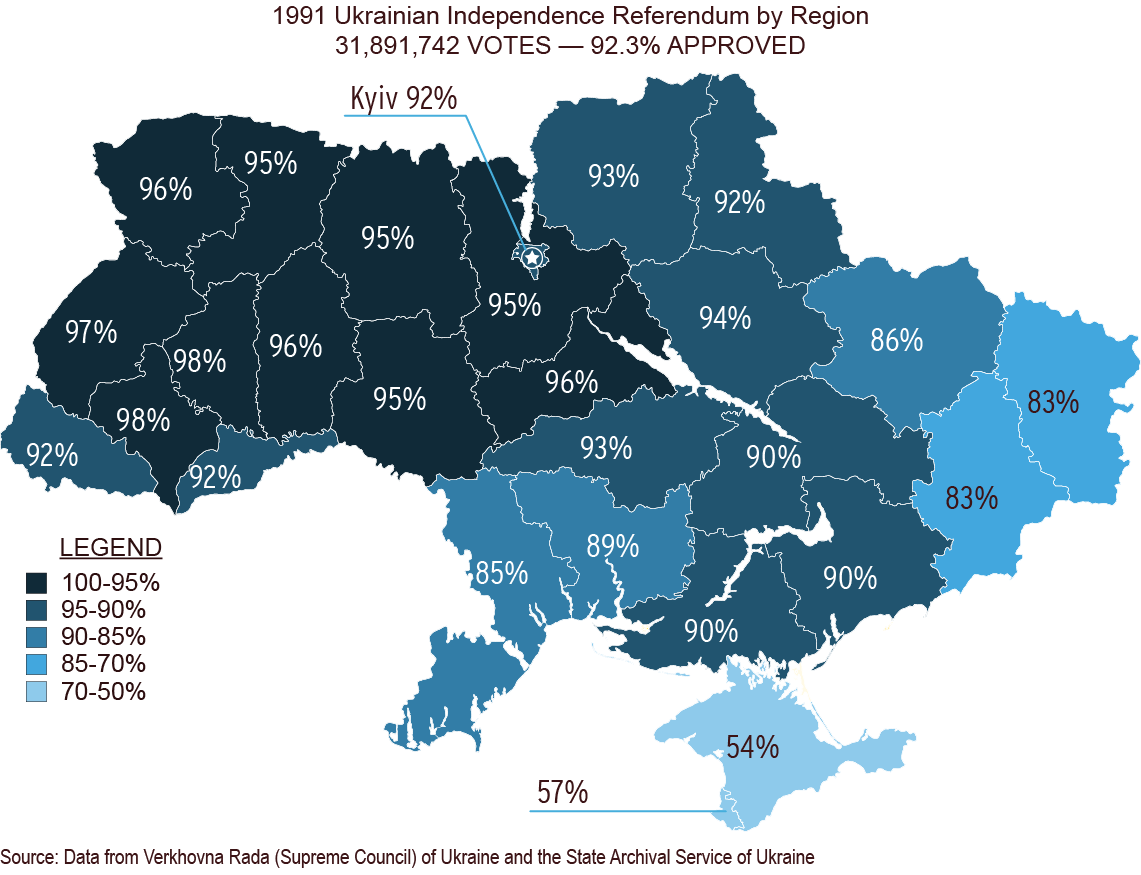

92% of Ukrainians voted to break away from the USSR in 1991

On December 1, 1991 “92 percent of Ukrainians who participated in a national referendum voted for independence.” In every region of the country, including Crimea, a majority supported breaking away.

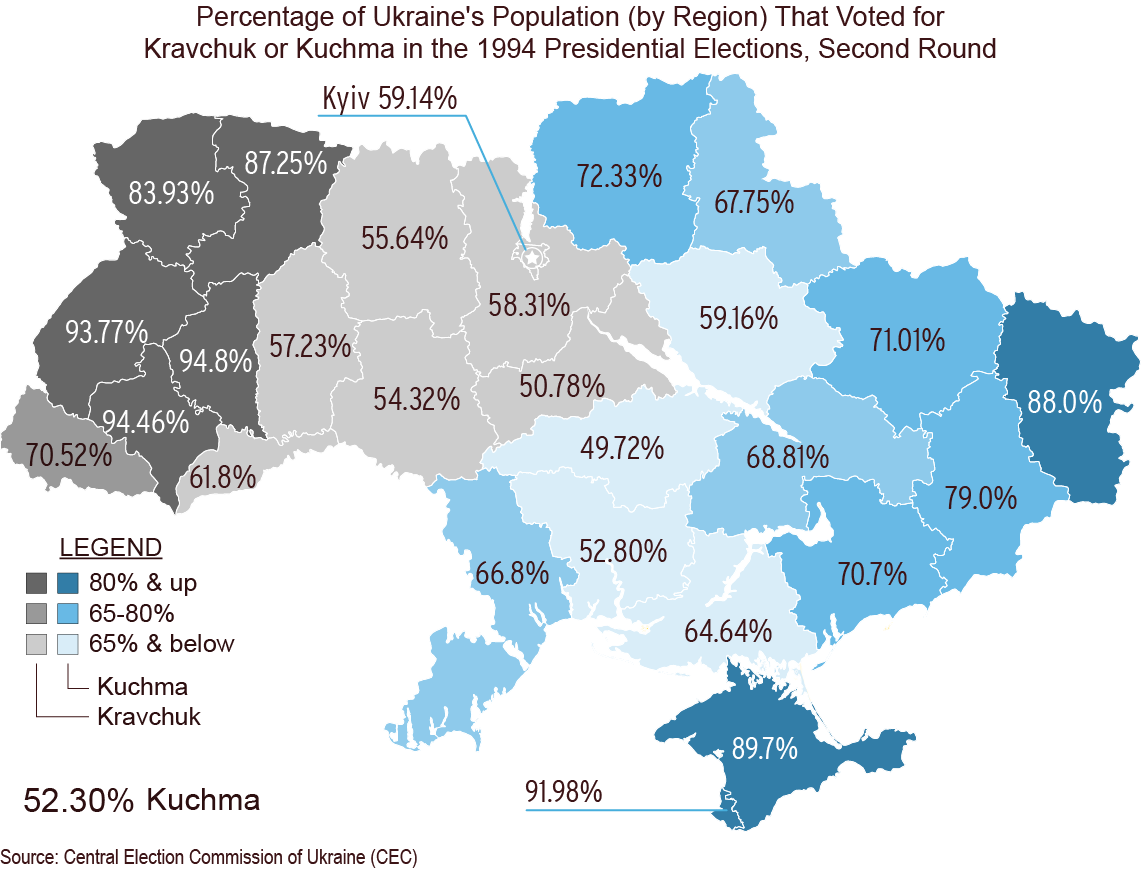

Ukraine’s first president lost his 1994 reelection bid, an important milestone for democracy

Freeland describes the newborn Ukraine as “accidentally pluralistic, allowing democracy to spring up through the cracks in the regime’s control. Proof of that came in 1994 when Kravchuk lost his reelection campaign. The very fact that he could be voted out of office was an early but important milestone for a fledgling democracy.” However, Freeland notes that “what followed was not exactly encouraging. Kravchuk’s successor, Leonid Kuchma, began to turn back the clock, harassing the opposition and the media.”

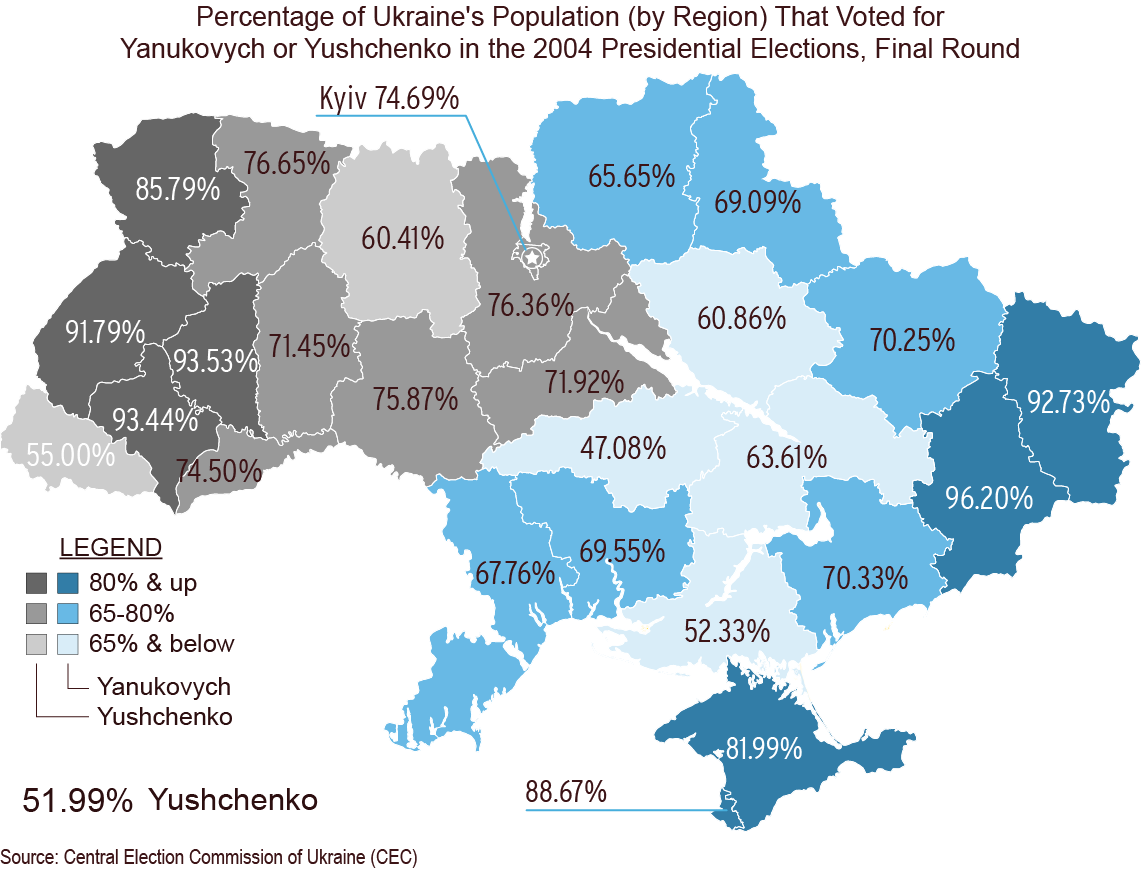

Ukrainians demanded a new election in 2004 after the government rigged the outcome

After 10 years as president, Kuchma was term-limited out of office but “was able to rig the 2004 election in favor of his dauphin, Viktor Yanukovych, who was prime minister.” The Ukrainian people responded with what became known as the Orange Revolution. “Ukrainians camped out in the Maidan — the central square in Kyiv — and demanded a new election. They got it.

“Then came a truly tragic irony. Yanukovych’s opponent and polar opposite was Viktor Yushchenko, a highly respected economist and former head of the central bank. He was the champion of Ukrainian democracy. Largely for that reason, he was hated and feared by many in Russia, notably in Putin’s inner circle. Yushchenko was poisoned on the eve of the ballot. The attempt on his life left him seriously ill and permanently scarred, yet he triumphed in the election.”

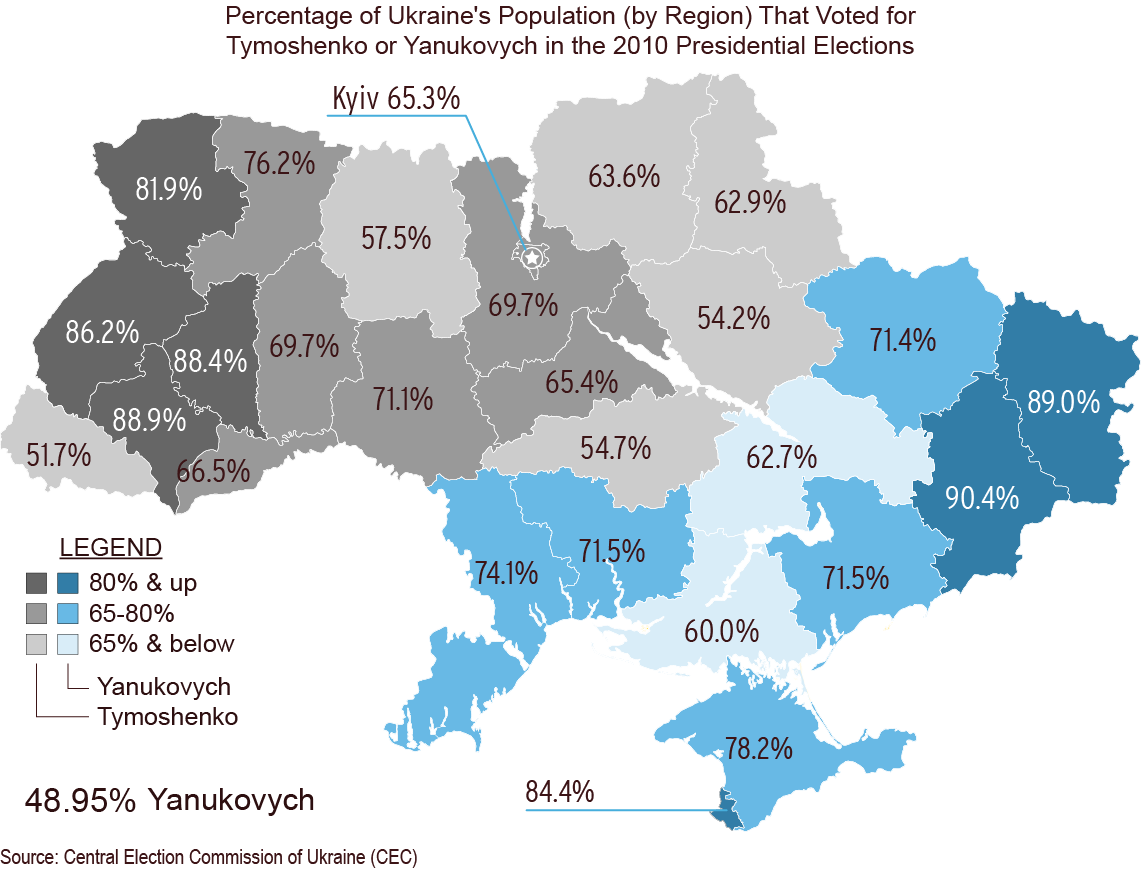

Yanukovych wins the 2010 presidential election fair and square

Freeland says Yushchenko “did such a poor job in office that Yanukovych, who had failed to become president by cheating in 2004, ended up being elected fair and square in 2010.”

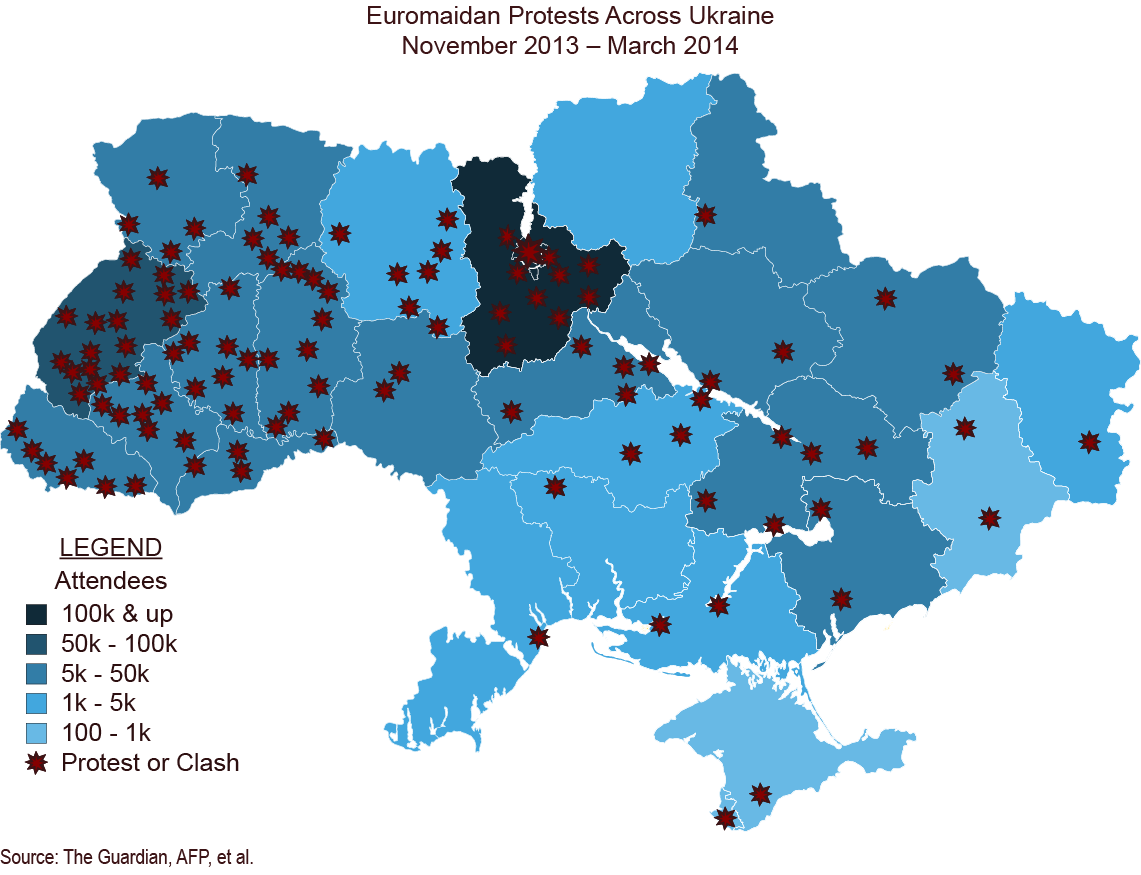

In 2013, protests erupted throughout Ukraine and president Yanukovych fled

In November 2013, Freeland explains that “Yanukovych reneged on a promised trade deal with Europe, part of a general turning away from the West, which set off a massive demonstration of people power.” With Moscow’s support, Yanukovych responded by unleashing “bloody force on the demonstrators.”

In the face of the Maidan Uprising Yanukovych fled Ukraine. This “enraged Putin.”

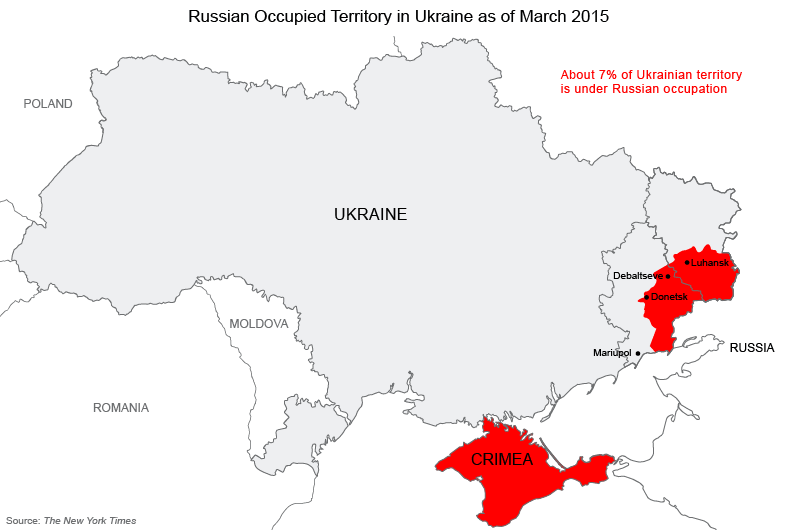

Russian President Vladimir Putin orders the invasion of Ukraine, taking over Crimea

On the morning of February 23, 2014, the final day of the Sochi Olympics, Putin ordered the takeover of Crimea, which Freeland described as “the grim beginning of a new era, and what might be the start of a new cold war, or worse.” Russian backed rebels have since taken over parts of eastern Ukraine and about 7% of Ukrainian territory remains under Russian occupation.

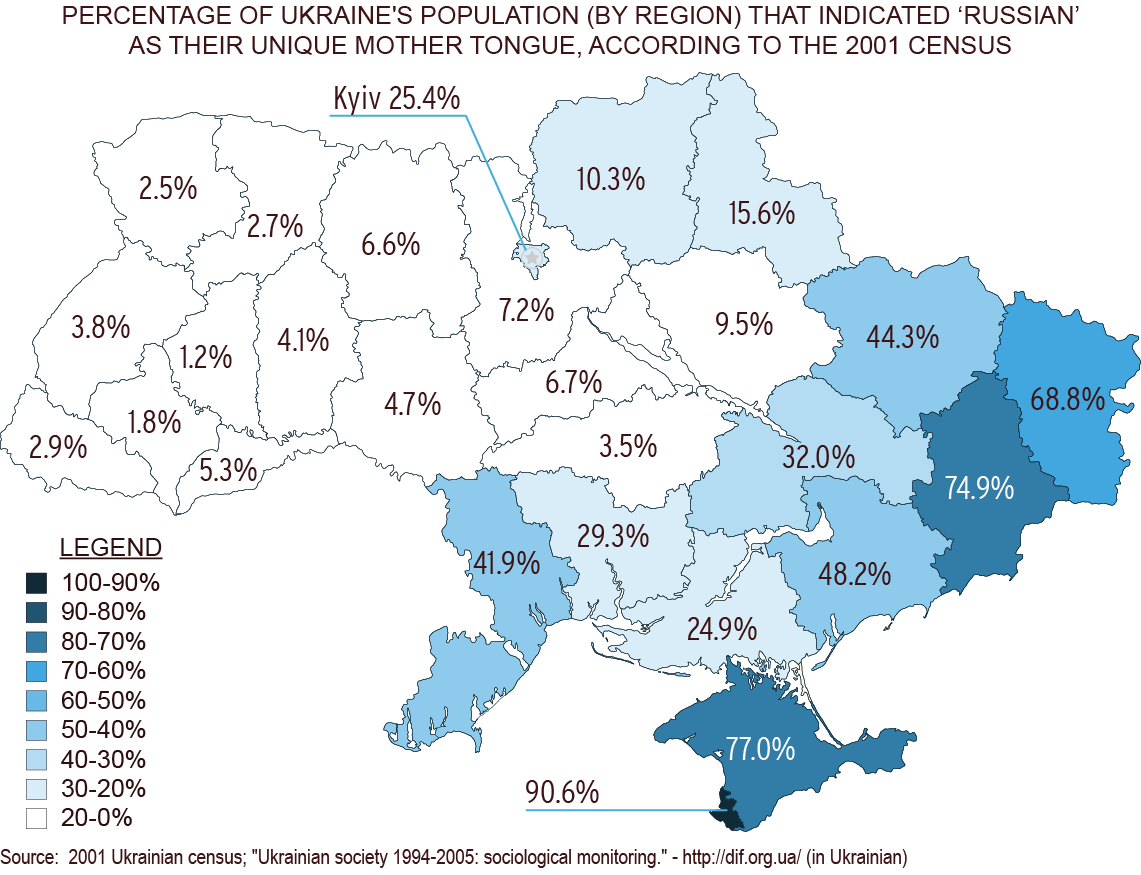

Russian is the first language of many Ukrainians and isn’t an indicator of support for Russian unification

In an audio clip from within Freeland’s essay, she highlights “one of the smartest and most effective things” Putin’s propaganda machine did was to frame the conflict in Ukraine as a civil war “between Russian-speaking Ukrainians and Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians.” Freeland emphasizes that “that was never true.”

She explains that “while the linguistic factor is real, it is often oversimplified in several respects: Russian-speakers are by no means all pro-Putin or secessionist; Russian- and Ukrainian-speakers are geographically commingled; and virtually everyone in Ukraine has at least a passive understanding of both languages. To make matters more complicated, Russian is the first language of many ethnic Ukrainians, who are 78 percent of the population (but even that category is blurry, because many people in Ukraine have both Ukrainian and Russian roots).”

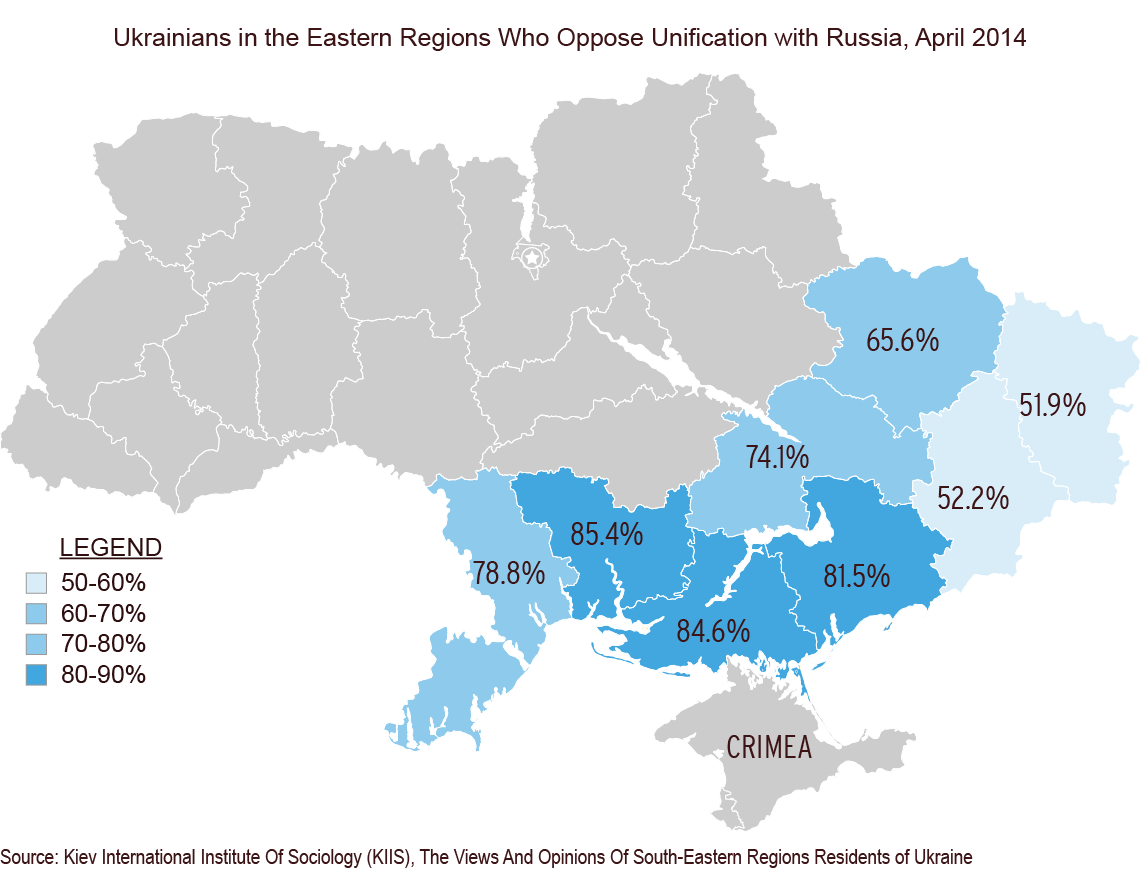

The majority of Ukrainians oppose unification with Russia even in the eastern and southern regions

A poll in April 2014 found that in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine, “nearly 70 percent were opposed to the unification of their region of Ukraine with Russia; only 15.4 percent were in favor.” Freeland says “It is worth underscoring that these strong views are the opinions of the lands Putin has claimed as “Novorossiya,” the largely Russian-speaking southern and eastern regions of Ukraine.”

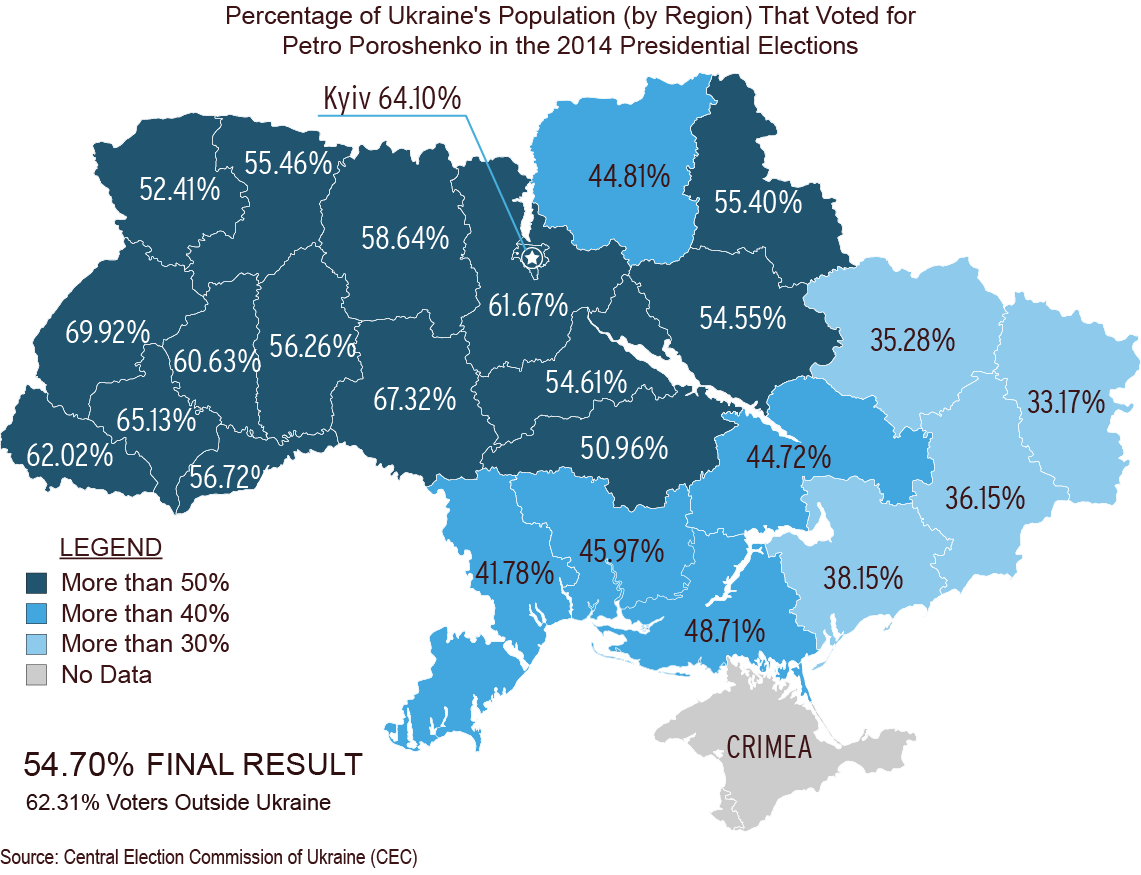

Petro Poroshenko wins first presidential election after Russian invasion

Petro Poroshenko was elected president of Ukraine on May 25, 2014. Freeland explains that Ukraine’s new leaders “are defining their national identity as inherently democratic and freedom-loving.”

For more on Ukraine’s struggle for independence in the face of Russian aggression, read Chrystia Freeland’s full Brookings Essay, “My Ukraine: A personal reflection on a nation’s dream of independence and the nightmare Vladimir Putin has visited upon it.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

10 maps that explain Ukraine’s struggle for independence

May 21, 2015