The five-year decline in fertility in the U.S. has ended, according to the latest statistics. Before we cheer this development, we should ask whether low fertility rates are a problem. In particular, if we want more upward mobility, perhaps low fertility is not such a bad thing. With fewer children to support, parents and society can both invest more in each child, helping them to climb the ladder and become productive citizens in their adult years.

So why are so many rich countries worried about population decline? The concern, of course, stems from fears that there will be too few people to support us in our old age. The greying of the population could be addressed by reforming immigration laws to allow more immigrants to come to America: unfortunately, growing nativism may make that a politically unacceptable solution.

Japan and Singapore: Can Fertility be Boosted?

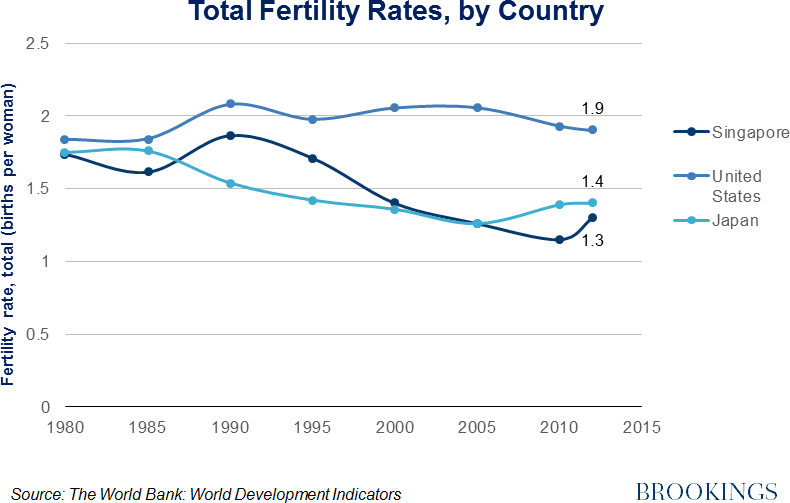

Are pro-natalist policies a viable option? Japan and Singapore offer instructive case studies. Like other Asian societies, their fertility rates are very low. At 1.2 births per woman in Singapore and 1.4 in Japan, they are well below a replacement rate of 2.1 and well below the current U.S. rate of 1.9.

Women are delaying marriage because of their careers, having children at older ages, and having fewer of them. Because unwed births are still stigmatized in these Asian cultures, births among young singles are almost nonexistent.

Singaporean parents receive paid maternity leave for 4 months, 6 days of paid child care leave per year per parent, large baby bonuses (cash and matched savings) of between $10,000 and $24,000 per child, tax savings, and many other benefits. But none of these benefits appear to have had much effect on the fertility rate.

Six Fertility Lessons

First, a fertility rate of 1.9 is nothing to worry about. It is still high by international standards and likely to tick back up as the economy recovers.

Second, young people cannot be “bribed” into having children through lower taxes or large baby bonuses. (Organizing work and school schedules to suit modern family life is likely to be more effective.)

Third, with fewer children, more public funds could be devoted to investments in education – expenditures that are badly needed if we want to remain economically competitive

Fourth, drops in fertility mean a smaller youth cohort 15 to 20 years later – a development that in the past has been associated with less crime and more jobs for new entrants.

Fifth, a comprehensive immigration bill could quell anxieties about financing our retirement costs, by allowing skilled workers from other countries to join our labor force.

Sixth, and most important of all, parents do a better job when they delay childbearing until they are ready to commit to both parenthood and marriage. If we could reduce early, unwed (and typically unplanned) parenting to Asian levels, lower fertility wouldn’t be a bad thing. Children would be better cared for and more upwardly mobile.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Should We Worry About Low Fertility?

December 17, 2014