Standard and Poor’s issued a new report this week arguing that high levels of inequality may be retarding U.S. economic growth, moving debates around the effects of inequality further into the mainstream.

The Unresolved Debate about Mobility and Inequality

One particularly contentious axis of the debate about inequality has focused on whether there’s any connection between income inequality and intergenerational mobility. Former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers Alan Krueger popularized the Great Gatsby curve, based on research from Miles Corak at the University of Ottawa, which portrays that countries exhibiting higher levels of inequality also experience lower levels of mobility across generations.

Scott Winship of the Manhattan Institute and Donald Schneider of Heritage, as chronicled on this blog, challenged that interpretation in a piece late last year (as well as in subsequent writings). The two researchers made use of great new data from the Equality of Opportunity project at Harvard and UC-Berkeley which measure US income mobility at the metropolitan scale by pairing the tax returns of parents and children across 30 years. Winship and Schneider ultimately find no significant relationship between the project’s measures of inequality and mobility for “commuting zones,” which approximate urban and rural economic regions.

Why Look at Mobility from a Metro Angle?

Inequality at the metropolitan scale could affect mobility over time if, for example, it leads to more racially and economically segregated neighborhoods and schools. The Harvard and Berkeley researchers find that low-income children growing up in metro areas with higher levels of segregation made less progress up the income ladder over time. Similarly, Melissa Kearney of Brookings’ Hamilton Project finds that high school dropout rates and non-marital childbearing rates, factors also associated with lower income mobility for the poor, are higher in areas characterized by more inequality.

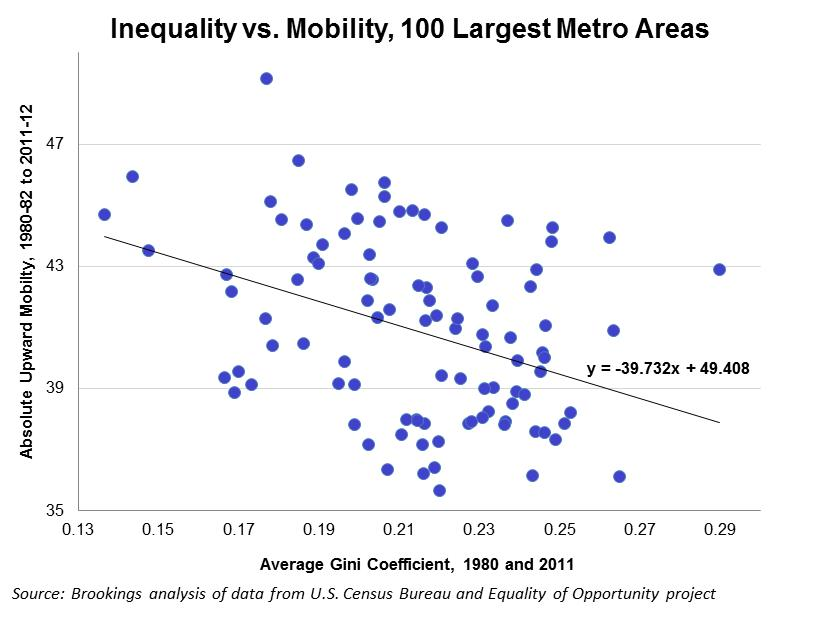

To investigate whether metro-level inequality might affect metro-level mobility, I plotted the average Gini coefficient (a standard income inequality measure, derived from Census Bureau data) for metro areas in 1980 and 2011 against the Harvard/Berkeley measure of intergenerational mobility for those same metro areas (provided on their website), which they calculated across a similar time period. It suggests that, in fact, metro areas where inequality is higher tend to show lower rates of intergenerational income mobility. The relationship is actually a little bit stronger among the 100 largest metro areas (depicted below), where the difference between a low-inequality metro like Boise and a high-inequality metro like Chicago translates into a predicted 3 percentile lower adult income for a child growing up in a 25th percentile family.

Is that a lot? Not exactly. Is it causation rather than simple correlation? I’m not sure. But it’s a reminder that efforts to promote social mobility—through channels such as education, norms around family formation, or economic development—ultimately take shape in local places that have their own distinctive economic dynamics, inequality among them. Whether or not there’s truly a “Metro Great Gatsby curve,” inequality warrants attention as potentially important context for those efforts in metro areas.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Does Inequality Matter for Mobility? A Metro View

August 7, 2014