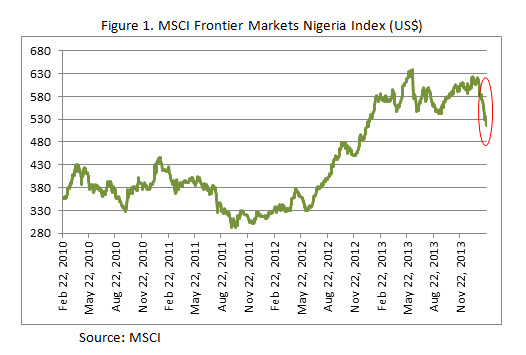

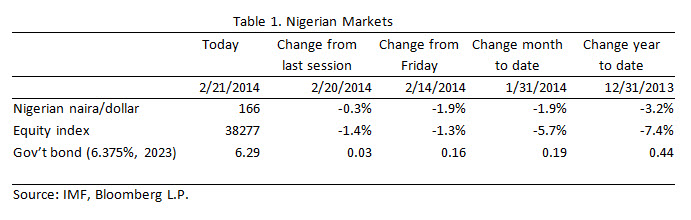

The suspension of Nigeria’s central bank governor, Lamido Sanusi, has led to increased market volatility within the country (Figure 1 and Table 1). Bloomberg reported on Friday that the Nigerian naira slumped to its lowest level since 1999 after reaching 168.9 per dollar on Wednesday. That day, trading in the domestic bond market was halted, and the benchmark stock index fell to its weakest level in three months. However, eurobond yields were little changed at 6.32 percent after jumping the most on record by 12 basis points. The current event is reminiscent of the financial turmoil in Indonesia in 2010: In that case, the local stock exchange fell 3.8 percent (the sharpest in 17 months), and the rupiah lost 1 percent against the dollar following the resignation of Finance Minister Sri Mulyani.

Mr. Sanusi’s sacking has come after he submitted to the Senate a report detailing the failure of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNCP) to transfer $20 billion to the government. Although the NNPC dismissed the governor’s claims, there has been increased criticism of President Goodluck Jonathan’s resolve to fight corruption. The former governor was a darling of foreign investors who liked his solid track record fighting inflation and safeguarding financial stability. It is therefore no surprise that market participants are being unnerved by his dismissal. Furthermore, market participants are questioning the independence of the central bank, now that its governor has been dismissed by politicians.

The timing of Governor Sanusi’s sacking could not be worse, as Nigeria was already battling the spillover effects of the tapering of the United States Federal Reserve. The central bank is now facing additional pressure on its currency. So far, central bank intervention has helped slow the fall of the naira, but that has been at the cost of losing foreign currency reserves. It is therefore not surprising that Finance Minister Okonjo-Iweala has made statements to reassure the markets, and the president quickly announced a replacement to Governor Sanusi.

Late last year, the International Monetary Fund warned that, although Nigeria’s outlook is positive with growth projected to increase to about 7 percent in 2014, the country could be affected by a number of risks. IMF economists identified potential shocks such as a decline in oil prices, the pace of recovery in global economic and financial conditions, capital outflows, continued losses in oil production, and increased security concerns. It also cautioned against the temptation of procyclical election spending (elections are scheduled to take place next year). The IMF statement now appears to be prescient.

Whether the extent of the market effect of the dismissal will be short- or long-lived is not clear. But what is clear is that it does not augur well for Nigeria. In the end, what really matters will be how strong Nigeria’s fundamentals will be. The country relies heavily on oil exports (70 percent of government revenues) and is riding on current high oil prices. But the Nigerian government should realize that a central bank not subordinated to political demands is a key tool in establishing strong economic fundamentals. An independent central bank can help fight inflation effectively, ensure predictability, anchor investors’ expectations, and, in bad times, resist printing money to fund the budget. Moreover, if Nigeria is to play a leading role in fostering regional economic integration, it has to continue leading the way in building an effective monetary institution.

Commentary

How Much Will it Cost to Sack Nigerian Central Bank Governor Sanusi?

February 24, 2014