In mid-march, I had the chance to visit my country, Israel, this time with a delegation of the Inter-American Development Bank, in order to learn about the innovation “ecosystem” that has drawn the attention of so many in recent years. I know Israel very well. Yet, before this trip, I never had the chance to look in detail at the policies that stand behind the Israeli innovation engine.

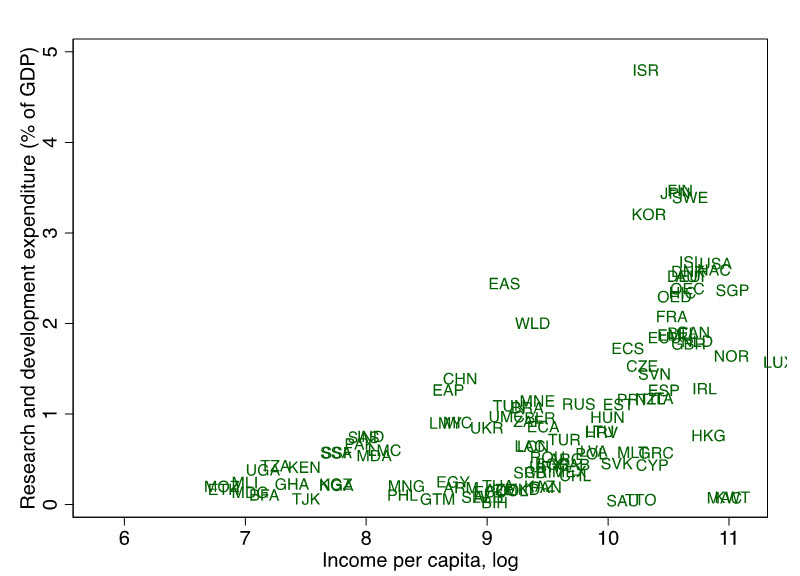

Israel has the highest budget for R&D as a proportion of its gross domestic product in the world, as can be seen in the figure below.

Israel invests about 4.5 percent of its GDP in R&D. This number goes far beyond the OECD 2.2 percent average, and much more than many other countries at the same level of income.

This is not a coincidence. It is linked to the fact that Israeli governments have been pursuing policies to foster innovation for decades now. The Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) of the Ministry of Economy, an independent authority managed by professionals (and not politicians) are in charge of creating public policies to support the private sector by fixing important market failures that could hinder innovation. If one had to pick the most important role the OCS has, it would be risk- sharing. By collaborating with the private sector to inject “risk capital” into the economy, the government shares the risk that otherwise the private sector alone would be unwilling to take. Moreover, the OCS is very careful to create programs that avoid crowding out private investment, always asking the question: what is the market failure we are trying to solve?

An important example of this is their incubators programs. The OCS supports about 20 “certified” incubators in the country—which finance and house startups with innovative technologies—by providing about $7 for each $1 invested by private investors. Yes, you read right: The OCS subsidizes about 85 percent of investment in incubators. Incubators help firms to start up, in the hope they will eventually “exit”—be sold to a larger company—or go through an IPO that would take them to the NASDAQ.

The ecosystem, however, goes beyond the help of the government. Universities and research institutes have highly professional Technology Transfer Offices that work with researchers to patent and commercialize new technologies that come out of their work. Both the researchers and the institution share the profits that could come out of a successful enterprise.

While there are many other factors that also play an important role in the success of this ecosystem (mostly related to culture such as risk-taking behavior and not being afraid of failure), there are important policies that developing countries could learn from. The challenge for developing countries is to internalize the benefits of long-term strategies that often are put aside due to short-term political considerations.

Israel’s innovation ecosystem is flourishing. It is without a doubt the engine of the economy. However, everything comes with tradeoffs. Israeli entrepreneurs dream of early exits, and many of them have achieved this dream. In 2014, exits from Israeli startups reached an all time high of about $15 billion. These entrepreneurs collect huge amounts of money, which they were able to get thanks to their talent and also to the money of all taxpayers. The challenge for Israel is to find a way to “give back” to the struggling professional middle class that, through their contributions, play such an important role in keeping the ecosystem alive and well.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israel’s innovation paradise: Where risk-sharing and public investment are paying off

April 3, 2015