According to a Gallup nationwide poll ten years ago, 55 percent of citizens approved of the way Congress was handling its job. That was in March 2001, before the surge in solidarity that resulted in Congressional approval ratings of 70-80 percent following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. By mid-2002, the approval ratings were back to pre-9/11 levels, at 54 percent in July 2002.

By July 2009, Congressional approval ratings declined to just 32 percent. Just prior to the debt-ceiling debate three weeks ago, they stood at 18 percent. These poll figures contradict Gallup’s expectation that there would be a surge in Congress’ popularity following the 2010 midterm elections. It had been suggested that Congress’ ratings may rise since that had been observed following some prior midterm elections. But not quite.

It may come as no surprise if the next Gallup poll, expected to come out in mid-August, shows Congress’ approval ratings hitting an all time low. Another poll, conducted by Rasmussen more recently, reported a few days ago that only 6 percent of U.S. voters rated Congress’ performance as good or excellent, a new low in their poll. Their previous monthly low was last month— only 8 percent of U.S. voters rated Congress as good or excellent.

These polls speak to the dim view that voters have of how well Congress has been doing its job in general— not just related to the debt ceiling paralysis. Since this picture, based on the views of citizens and voters is not unknown to many in Washington, there is no need to belabor it further.

What is less recognized in the U.S. is the extent to which the private sector holds a dim view of Congress, and how this contrasts with how the private sector views the effectiveness of parliaments in other countries.

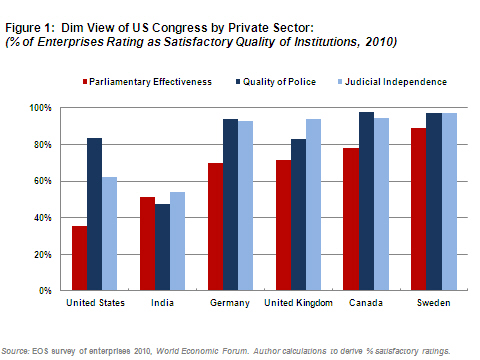

From our large worldwide governance databank that include dozens of sources, we can draw from one particular source first, namely a large survey of enterprises around the world. The World Economic Forum conducts annual surveys of over 10,000 private sector executives in over 130 countries. A simple analysis of the reports of those enterprises suggests how abysmally low the U.S. private sector their Congress (first column, Figure 1).

If one compares the ratings for the U.S. Congress (lowest by far of any institution in the U.S.) with that of other institutions, we find that U.S. respondents do not have a dim view of the whole public sector or of simply any public institution. In Figure 1, we see the large gap in how the private sector views Congress as compared with either the police or the judiciary.

We also see in Figure 1 how differently the private sector in other countries views their own parliaments. It’s interesting that these ratings do not differ substantially across OECD countries, including the U.S., for institutions other than their parliaments.

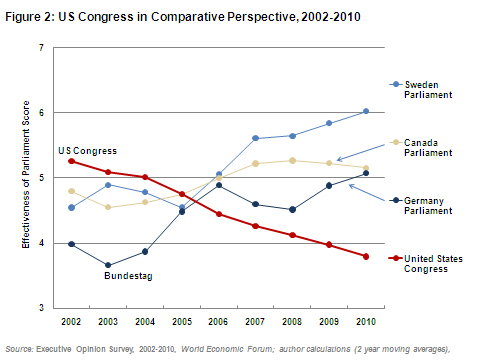

Moreover, in countries like Germany, Canada and Sweden, there has been a positive trend in private sector confidence in their legislative body, which contrasts with the U.S.’s downward trend (Figure 2). If we only look at the U.S., we see that today’s dismal ratings of Congress’ performance need not be the case given data from previous years. In fact, the private sector’s assessment of Congress’s effectiveness was much higher in 2002, but has steadily declined. By the time the 2011 data is available, it is highly likely that the downward trend regarding the views on the U.S. Congress will continue.

In fact, more broadly, our Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) point to the fact that for some time the U.S. has been far from a model country in governance. At the start of the past decade, there were 15 countries around the world with better governance on average than the U.S. By the end of the decade, there were over 25 countries with better governance than the U.S. Such subpar performance in general on governance performance can be attributed in part to the performance of Congress.

A dysfunctional U.S. Congress may be the talk of the town and the world today. But empirical evidence suggests that it need not be the case. Other U.S. public institutions are performing much better in the eyes of the public and the private sector. Parliaments in other countries are doing well and improving over time, which shows that legislatures can be effective. The U.S. Congress itself has seen much better days. The American people and the world are hoping that Congress can rise to the task at hand given the urgent need to raise the debt ceiling in order to avoid the threat of another global economic and financial crisis.

Commentary

Congress’ Dismal Performance Need Not Be the Case: A Governance Perspective

July 29, 2011