Last Sunday’s New York Times Magazine cover story, “A Dream Undone,” chronicles the history of recent successful efforts to undermine the Voting Rights Act. The passage of state measures which effectively restrict voting for some groups comes as the nation’s racial minority populations—blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and others—are showing increasing electoral clout.

Yet, restrictive voting provisions such as stringent Voter ID laws and limits to early voting and voting hours in heavily minority communities will not adversely impact voting in the way the provisions’ authors intend. As I state in my book, “ … over the long haul, the effects of such attempts to suppress voters will pale in comparison to the larger demographic sweep of diversity that will shape the nation’s civic decision-making.”

Simply put, the sheer force of our diverse demographic change (racial minorities account for 95 percent of our growth), will render such measures meaningless. However, in the near term—meaning the next couple presidential election cycles—voting restrictions that disproportionately impact minorities could be costly just as they are beginning to find their voice in the political arena.

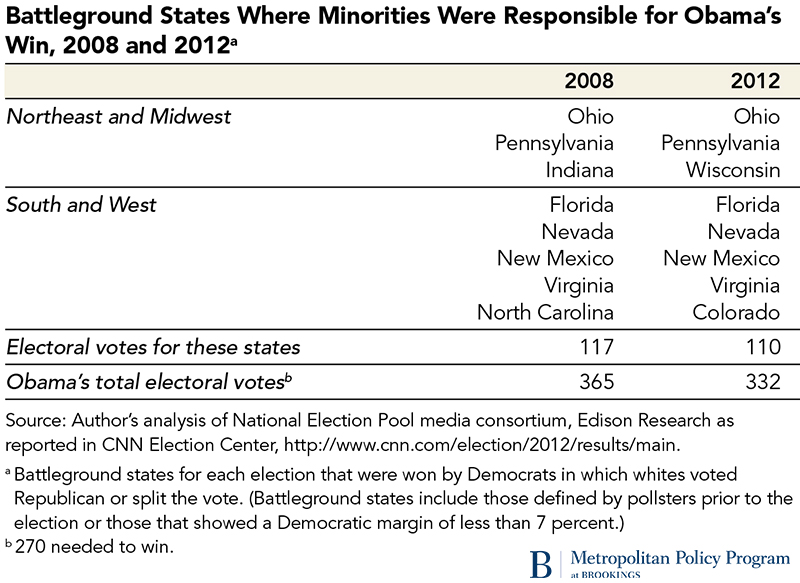

There is no question that minority support was largely responsible for President Obama’s wins in both 2008 and 2012. The combined minority vote gave him net advantages 21.2 million and 23.5 million over his Republican rivals, John McCain and Mitt Romney. (These countered and bested the net voting advantages of 11.7 million and 18.6 million that whites gave his rivals) And in the Electoral College, minorities were solely responsible for his winning key swing states that put him over the top—accounting for nearly one third of his total Electoral College votes each time. These included once Republican Southern states, Virginia and (in 2008) North Carolina, home to new populations of Hispanics moving into the region and blacks returning to the South; and Mountain West states including Nevada and Colorado whose voting populations continue to become more racially diverse.

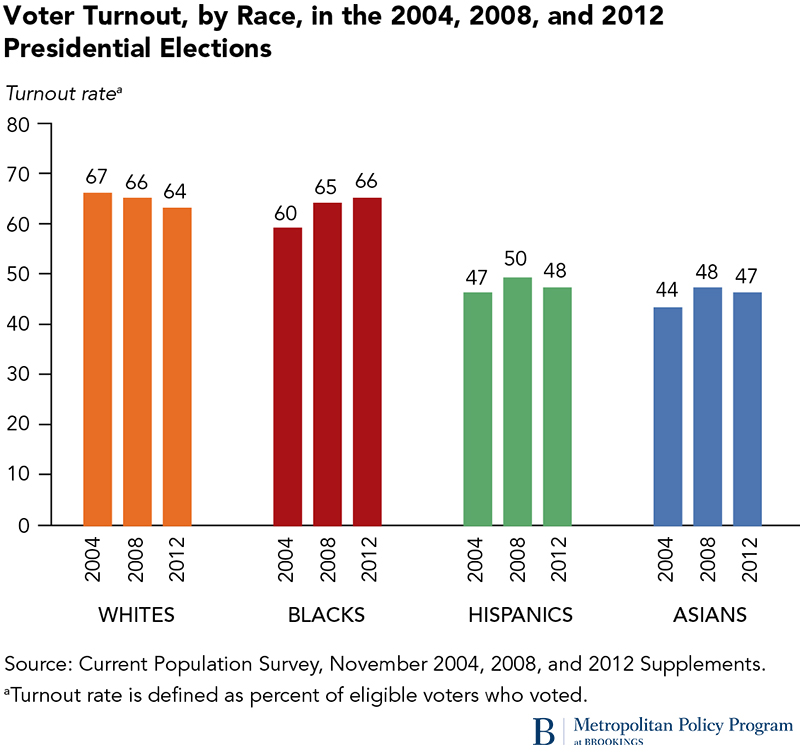

Changing demography, while important in the long run, is only one reason that Obama won. Equally responsible for his wins was the increased turnout among eligible minority voters—Hispanics, Asians, and especially blacks. Black turnout rates for the last two presidential elections were higher than in 2004 or in any election since 1968, when such data began to be collected. In 2012, the black turnout rate exceeded white turnout nationally for the first time ever, and Hispanic and Asian turnout for these two elections were higher than in any election since 1992.

My analysis shows that this increased minority turnout was indeed responsible for Obama’s win in the 2012 election. That is, if minorities turned out at lower 2004 levels and voted just as strongly for Obama, the race would have been a virtual toss-up. And in important but close swing states like North Carolina, Florida and Ohio where minorities alone were responsible for Democratic wins, the strength of minority turnout was especially important. Of course the candidate preferences for those who did turn out are also important, and on this score Obama did better than previous Democratic candidates among minority voters. But turnout, unimpeded by bureaucratic or other hurdles, was key.

It is unknown whether the 2016 Democratic candidate, be it Hillary Clinton or someone else, will generate the strong enthusiasm among minority voters that Obama did. But the 2012 election made clear that the ability of minority voters to cast a ballot unimpaired is especially important in this time of rapid demographic change. Although Democrats ostensibly will be the near term winners of the unencumbered political participation of minorities, Republicans cannot afford to alienate Hispanic, black, and Asian voting blocs that are a growing part of the nation’s citizenry as well as its electorate.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Voting rights, minority turnout, and the next election

August 3, 2015