My previous TechTank post described the expanding reach of technology and, consequentially, the growing availability of information in Africa, Latin America and elsewhere in less developed countries. Rather than speak of failed states I refer to “areas of limited statehood.” An area of limited statehood involves several possible dimensions of failed service delivery, or an inability to enforce binding rules with legitimate use of force. A slum, for example, even in the heart of a nation’s capital, if it is devoid of public goods like sanitation, security, or even basic infrastructure, is an area of limited statehood. So, too, would vast stretches of rural countryside beyond the reach of the administrative capacity of the national government. The Eastern DR Congo fits this pattern.

Using Technology to Address Governance Shortfalls

In this post, I offer examples of the use of technology that at least partially address governance shortfalls in areas of limited statehood. Put another way, I describe how technologies are used to provide for public goods, such as security, sanitation, drinkable water, and economic opportunity. Where states are consolidated, agricultural extension services, for example, provide farmers with information essential to the important work of feeding families and communities. Where states lack that capacity, NGOs use available technologies to fill the governance void. For instance, the Grameen Foundation’s Community Knowledge Workers initiative serves more than 176,000 farmers living beyond the reach of state services through a network of more than 1,100 peer advisors. Using mobile technology to connect the advisors with the latest developments and to other farmers, smallholder farmers get accurate, timely information to help them meet their goals. M-Farm in Nairobi similarly provides Kenyan farmers with the latest crop pricing information and other valuable knowledge needed to sustain viable operations. International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the World Trade Organization and the United Nations based in Geneva, offers a variety of similar services – called Trade at Hand — to farmers around the world.

Technology in the Health Sector

In the health sector, digital technology delivers or sometimes collects vital health-related information regarding people living in areas of limited statehood. Medic Mobile offers a variety of technology-based services, including Muvuku, a SIM card-based data collection system that can collect and send health-related information from the field. Stopstockouts is a program in Kenya, Malawi, Uganda and Zambia that tracks medicine “stockout,” occasions when essential medicines are unavailable to patients at health clinics or pharmacies. Using mobile phones, texting software and geographical information systems (GIS) to create a digital map, researchers were able to show the extent to which citizens were left without essential medicines.

Technology can Improve Security

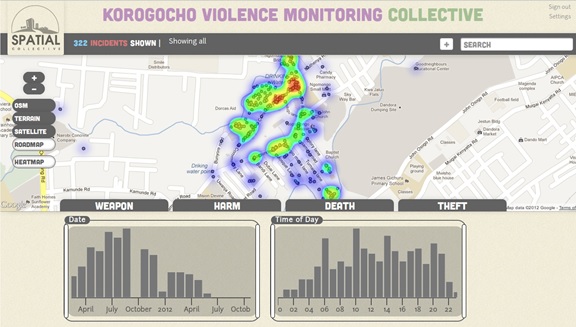

Perhaps the principal public good is individual and collective security. Yet in many places in the world, the police and military are woefully underfunded, poorly trained, and, as I will discuss in our next post, largely unaccountable to the people they are suppose to protect. Most often, communities are left to fend for themselves. This includes even awareness of the severity of the insecurity. There are no crime statistics. Spatial Collective, a social enterprise firm in Nairobi, was asked to “map” crime in Nairobi’s Korogocho slum. Working with the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD), Spatial Collective created a “heat map” of various types of violent crime in Korogocho. The data were collected from citizens and displayed on a GIS platform. With this sort of information, communities can respond to crime and violence in a more informed manner, even when doing so on their own and without the assistance of accountable and effective policing.

Information technology lowers what social scientists call communication and collaboration costs. Governance involves processes of cooperation and collaboration. Historically, information costs constituted the major component of governance, a cost met by state institutions and supported by taxes. This is still the best and most effective way to provide public goods. But where the state is missing or too weak to enforce binding rules and provide public goods, digitally enabled collective action initiatives such as those mentioned here fill in some of the governance void.

Part two of a three part series on ICT and governance. Part 1 is available here and Part 3 here.

Dr. Steven Livingston is professor of Media and International Affairs at The George Washington University. Among his more recent publications are Bits and Atoms: Information and Communication Technology in Areas of Limited Statehood (Gregor Walter-Drop co-editor) and Africa’s Information Revolution: Implications for Crime, Policing, and Citizen Security.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Transformative Impact of Data and Communication on Governance: Part 2

April 7, 2014