Pell Grants, providing assistance to low-income families, cost more than $30 billion a year. The maximum grant is close to $6,000 a year per student, more than the amount provided by virtually all other antipoverty programs.

So what are we getting for this expenditure? Not as much as we should. Although Pell Grants increase enrollment in higher education, there is no evidence that they increase rates of graduation. A substantial portion of Pell money is used for remedial courses designed to teach students what they didn’t learn in high school. But students who are not ready for college are likely to join the millions dropping out every year.

Target performance, not just poverty

One solution to this problem is to make financial assistance more conditional on student performance in high school as well as on family income. Here’s how it could work. Starting no later than 9th grade, students would be counselled on what is required to do well in college and the kind of courses, GPA, and test results likely to secure them a spot. Those who achieved a basic level of proficiency would be assured of financial support. That support would be more generous than current Pell Grants. Those who performed poorly (say, the bottom 20 percent of high school graduates) would not qualify for aid—although they could receive some support for other training or education programs.

The major purpose of this reform would be to encourage more learning before college: in high school or even earlier. Good counselling and not just more financial aid would be critical. But once the message got out that generous assistance would be provided to those who performed well, the hope is that kids would attend classes more regularly, study harder, seek extra help, and take more challenging courses. Schools would also work harder to enhance their reputation by graduating more “college-ready, Pell-eligible” kids. And parents would be more likely to nudge their children toward gaining eligibility for the program.

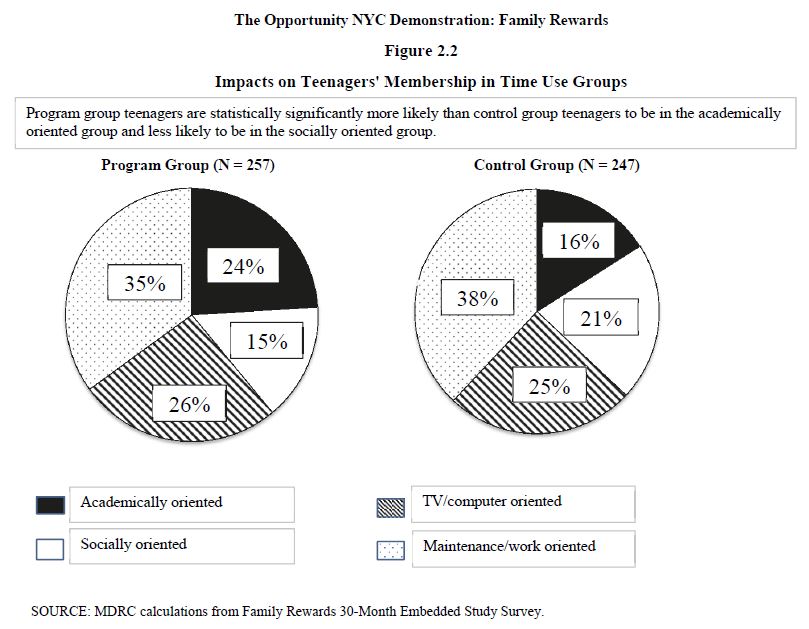

These are reasonable hopes: when a New York City program providing extra cash transfers to low-income families with children who passed the state regents exam, the proportion of students engaged in more academically-oriented out-of-school time increased from 16 to 24 percent, according to a careful evaluation by MDRC:

The effects were concentrated among and larger for students who were already proficient in math or reading at the end of 8th grade, suggesting that, to have the desired effect, any such effort must motivate students early in their schooling years.

Education is a partnership between students and their teachers or other school personnel. As the U.S. continues to fall behind not only in the numbers but also in the skills of college graduates, an emphasis on access without more attention to quality is a mistake. If postsecondary institutions are pressured to hand out credentials whose market value diminishes over time, their graduates will be short-changed in the process. Performance-based Pell Grants would recognize these basic facts.

Up next: Brad Hershbein on a more complete financial aid package for students.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Make Pell Grants conditional on college readiness

October 20, 2015