Education is key to social mobility. But poverty, especially when compounded by race and class isolation, leads to profoundly unequal educational opportunities and outcomes. Almost 50 years ago, James Coleman found that the main determinants of school success were the social and economic circumstances of the students. The educational achievement gap is mainly the result of an unequal opportunity structure that shapes the life chances — real and perceived — of youths from different social and economic circumstances.

What happens when college is free?

So what happens when one of the most obvious educational barriers facing the poor—the cost of college—is reduced or eliminated, as with Kalamazoo Promise? The stated purpose of the anonymous funders of the Promise is to spur local economic and community development. Other civic leaders have expressed the hope that the Promise will:

- Persuade professionals to move into the Kalamazoo school district with their families

- Create a “college-going culture” in the city’s low income neighborhoods

- Spur educational reforms to boost college preparedness and enrollment

The Promise abruptly reversed the district’s long-running enrollment slide, as the previous blog in this series showed. School enrollment has increased by nearly 25 percent and the city’s population once again has begun to grow. College-going rates have increased significantly, as Brad Hershbein will show later this week. However, there has been no major influx of professional families. In fact, the percentage of students receiving free and reduced lunch increased from 57 percent to 71 percent.

Kalamazoo kids remain poor

More than one-third of children in the district are below the federal poverty line, and 14 percent are in deep poverty—at or below 50 percent of the poverty line. Four in ten live in neighborhoods of highly concentrated poverty (40% poor or more). Income inequality in the Kalamazoo area is above the 80th percentile for US cities—a correlate of low social mobility, according to Raj Chetty, and a predictor of a wide range of social problems in the US and internationally. A recent comparative analysis of social mobility found that Kalamazoo County has lower social mobility for poor children than more than four-fifths of all U.S. counties. While this analysis was based on data that predate the launch of the Promise, there is little evidence —yet — that the Promise has influenced rates of social mobility.

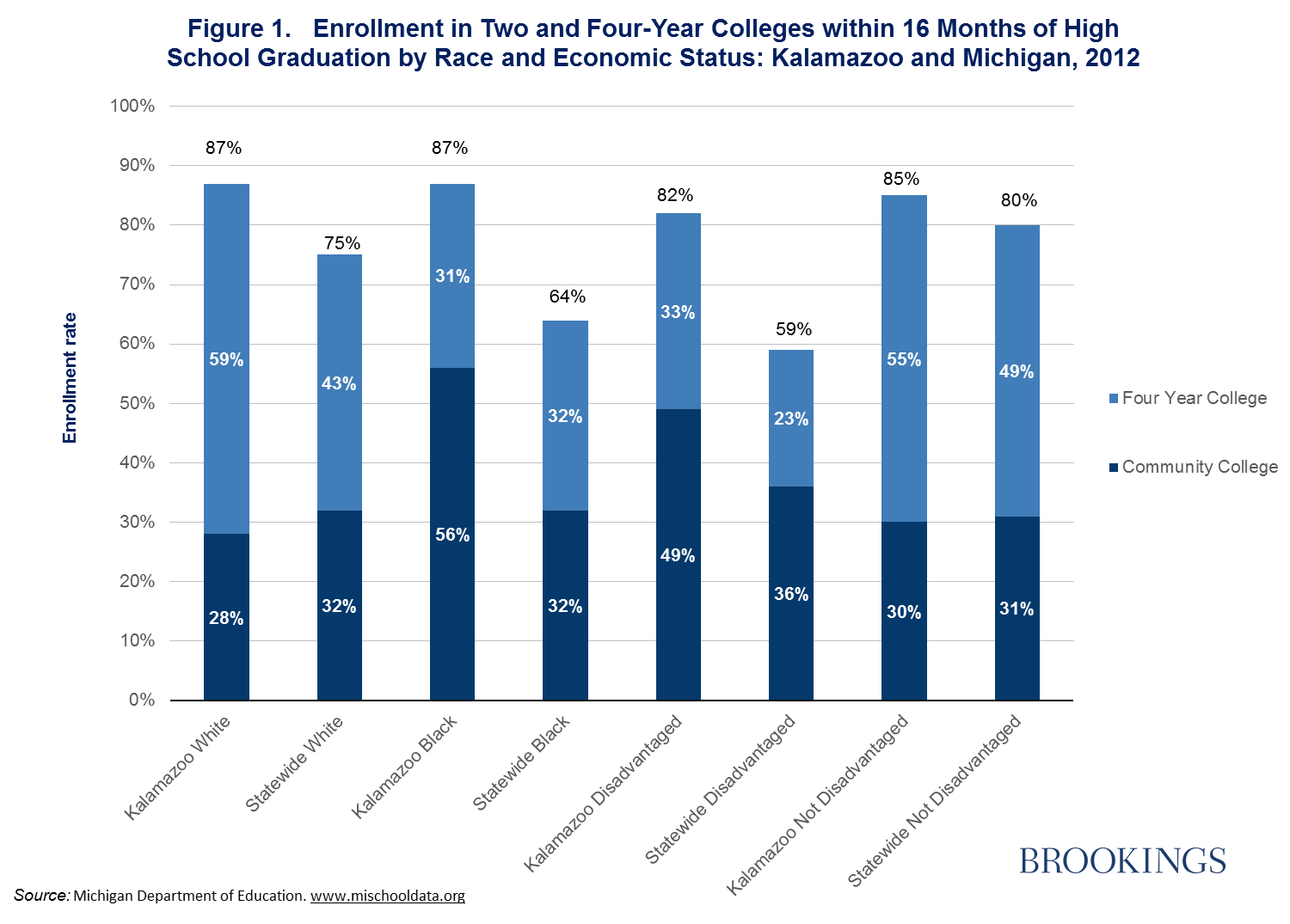

Kalamazoo graduates from the class of 2012 are more likely than their counterparts statewide to have enrolled in college. Remarkably, there is little difference in enrollment rates by race or economic status:

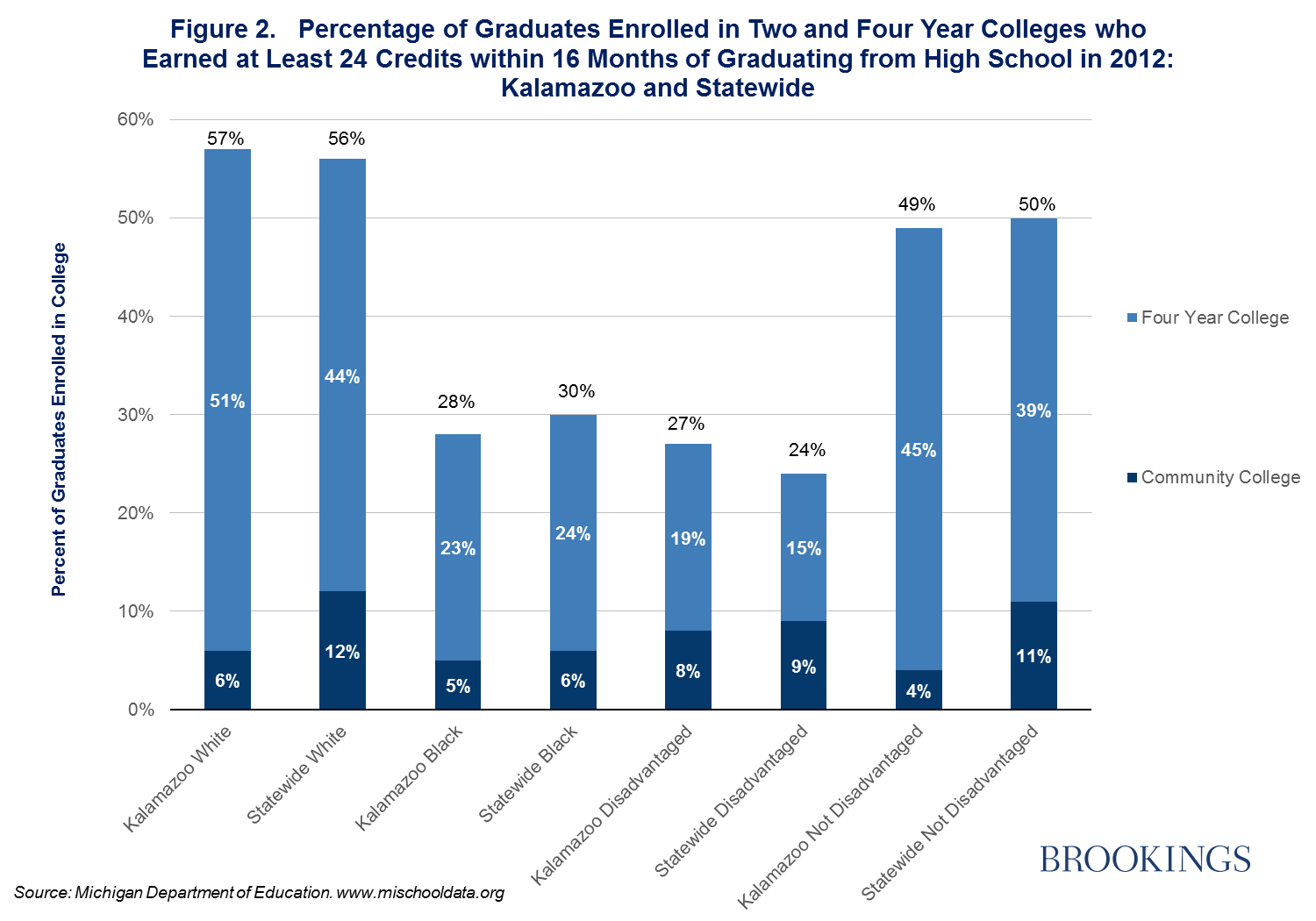

This looks like good news: and it is. But the news is less good when it comes to completion rates and by comparison to general trends. Kalamazoo high school graduates were little, if any, more likely than their counterparts statewide to have earned 24 college credits within sixteen months of graduating from high school. White students were about twice as likely to have earned 24 credits than black students, as were middle class students compared to the economically disadvantaged. There are also wide gaps by race and economic background in the chances of enrolling in four-year college versus community college:

Nearly 90 percent of all graduates from the classes of 2006-08 were eligible for the Promise, and according to the Kalamazoo Promise office, 40 percent of Promise recipients earned a post-secondary credential within six years of high school graduation. But there are big gaps by type of institution: just 21 percent of graduates who enrolled in community colleges earned a postsecondary credential, compared to 65 percent who enrolled in a four year college.

Race gaps at every step

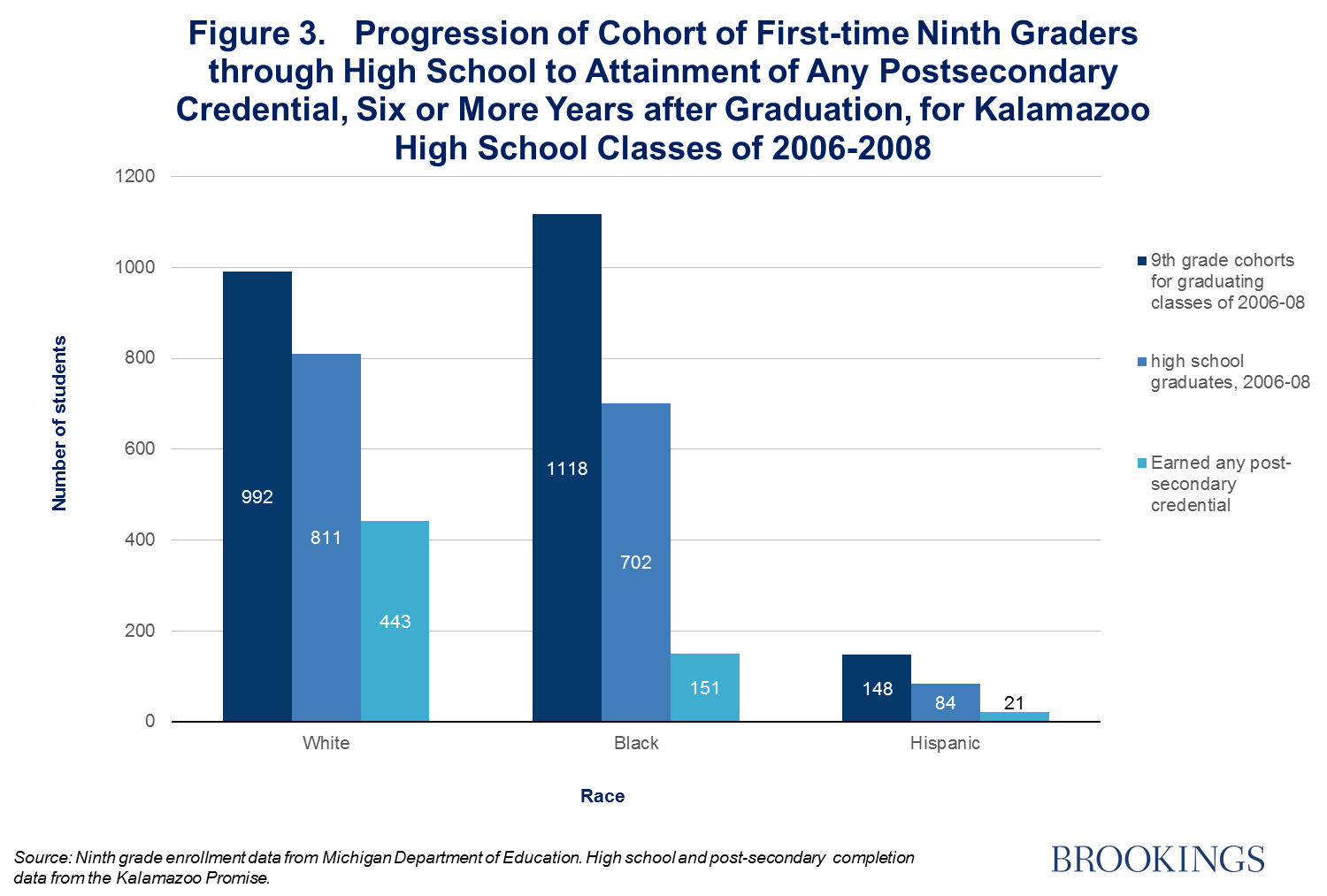

Race gaps are visible at each stage of the journey from high school through college. Figure 3 shows the number of black, white and Hispanic students, the number who actually graduated, and the number who earned any postsecondary credential six or more years after graduating. Among the ninth grade cohorts of the high school graduating classes of 2006-2008, more than one-third of all black and Hispanic students did not graduate:

Only about one in five black high school graduates, and about 13 percent of the black ninth grade cohort, had earned a post-secondary credential within six years of their expected high school graduation date. Similarly, only about one in four Hispanic high school graduates and 14 percent of the Hispanic ninth grade cohort had earned a credential. This compares to 54 percent of white graduates and 45 percent of the white ninth grade cohort.

Free college: Necessary but not sufficient for opportunity

Free college tuition is certainly a key component of any effort to reduce inequality of opportunity in Kalamazoo. But by itself, it is insufficient. Kalamazoo has launched initiatives such as Communities in Schools and the Kalamazoo Learning Network that have increased access to quality preschools. But more is needed to promote social mobility and community development. A new initiative, Shared Prosperity Kalamazoo is working to increase access to well-paying jobs, increase the number of strong, economically secure families and develop a stronger network of youth development programs.

Like most other U.S. communities, Kalamazoo has not yet come close to resolving the problem of inequality of opportunity for her children. The city’s Promise shows the potential but also the limits of free college tuition as a vehicle for more equal opportunity.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Free college is not enough: The unavoidable limits of the Kalamazoo Promise

June 24, 2015