Over the last couple of decades there’s been a knowledge boom in a number of areas that are highly relevant to teaching. How kids learn how to read. Managing classroom behavior. Teaching math fundamentals. Basic instructional strategies. If this new knowledge were to make it into the hands of teacher candidates, we could potentially see a big reduction in the all-too-steep learning curve experienced after entering the classroom.

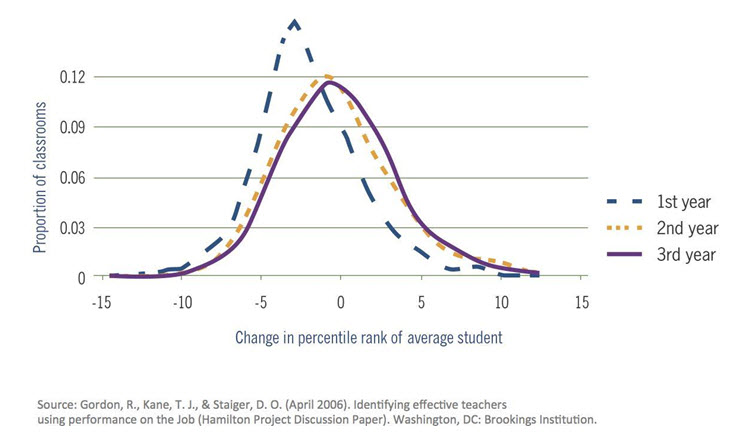

Most first-year teachers are decidedly less effective than even second-year teachers (see figure), prompting an important policy question: “How can this learning curve be reduced?”

It might be tempting to conclude good teaching is something that cannot be taught, which means on-the-job training is the best we can do and the learning curve is here to stay. Alternatively, maybe our teacher training programs could do better at conveying the most recent advances in the science of learning. We set out to on a project that explores this latter alternative.

Following on the heels of similar studies we’ve done on reading, mathematics and classroom management, a new NCTQ study Learning about Learning, finds little evidence that scientific advancements can be found in the coursework, specifically in the textbooks that are required reading, taken by aspiring teachers. The field of cognitive psychology has grown at warp speed over the last few decades. And, we would contend, there is no other subject that could benefit struggling teachers more.

Our methodology was straightforward and so were the results. To identify the knowledge teachers would want to help them design their instruction, we looked to a 2007 publication from the Institute of Education Sciences, in which a team of experts led by Dr. Hal Pashler of the University of California San Diego rigorously reviewed hundreds of studies. They found only a half dozen “fundamental instructional strategies” which have strong to moderate levels of evidence in studies that meet the rigorous standards set by IES, which they present in a great “practice guide” for educators. These strategies would benefit any teacher’s instruction – no matter what subject or grade level being taught.

Our analysts then combed a representative sample of 48 textbooks, looking for the smallest of references to any of these strategies (the list of textbooks can be found here). The sample included many widely circulated textbooks—three educational psychology texts were among the top five best sellers on Amazon.

What we learned was depressing. Not even one of the textbooks in the sample accurately describes all six instructional strategies…or five…or four…or even three. Roughly one in three of the textbooks that were read page for page failed to cover a single one. Most covered one or two. Whether the textbook was published before or after the IES guide made no difference in terms of coverage, even for the most recent editions of six textbooks in the sample, evaluated for the sole purpose of pinning down this conclusion. In any case, half of the studies supporting the six strategies were published before 2000.

There’s another aspect to what we learned about these textbooks which we haven’t given much play elsewhere, but which this audience might appreciate. The quality of references in most of the textbooks would likely not meet the standards of other professional training fields. Two-thirds of the supporting references direct readers only to a book without even a page number (imagine medical texts passing muster recommending a protocol supported by an ambiguous reference such as Your Spine and You, 2000. Chicago: Doubleday). More than half of the textbooks we reviewed cite none of the best studies on the topic, those same studies identified by IES.

Teacher candidates ought to get some value for the $40 million we estimate they are spending on these textbooks each year. There’s no evidence that they are irrelevant requirements in the courses that use them. From syllabi for the coursework from which the textbook sample was derived, we can see that teacher educators clearly use them to organize their teaching and assign regular readings from them each class. There were also virtually no instances of high quality supplemental readings accomplishing what the textbooks could not (such as the ideally suitable IES practice guide itself).

In light of their importance, you’d think publishers would be holding up and channeling knowledge that stands up to scientific scrutiny. No, it appears they are taking a pass and they’re giving their authors a pass on meeting standards that are common practice in any other field. So too are the peer reviewers chosen by these publishers who are routinely giving thumbs up to substandard texts.

The impact textbooks can have on the transfer of professional knowledge is essential and incalculable. The damage they can do—and are doing—when they leave out solid research or when they promote pseudoscience deprives teachers of essential knowledge.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).