When policymakers consider how to respond to a public health crisis, they tend to think in terms of quarantines, medical equipment supplies, and travel restrictions. Yet they too often miss a vital factor that countries like South Korea and Singapore recognized long ago—that public communications are just as crucial. Effective communication increases compliance with public health directives and saves lives.

As the current crisis has laid bare, too many countries lack a robust crisis communications infrastructure. The United States in particular should consider establishing a permanent federal health communications unit to build networks between local, state, and federal health authorities, and to develop and coordinate public communications strategies based on the latest research on health communications. Such an infrastructure would allow for key functions to be centralized and improve pandemic response.

Data collection. During a pandemic, the most basic information a government needs to provide are the number and location of cases. To that end, Singapore has created a dashboard with simple but effective data visualizations of COVID-19 cases. Likewise, Italy publishes daily statistics at Github. By contrast, in the United States, officials can’t even figure out how many tests have been conducted. The most authoritative numbers on cases, tests, and fatalities in the United States are published not by the Centers for Disease Control, but the COVID-19 Tracking Project, a joint project produced by the Atlantic magazine and Silicon Valley coders.

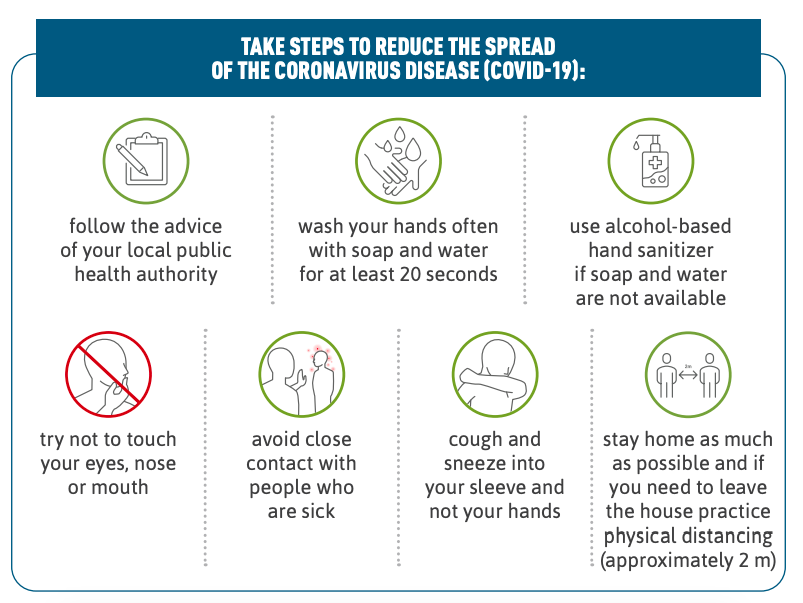

Data visualization. Effective communication in the time of a pandemic also requires government officials to move away from standard-issue tables. Full-color graphics like flow charts, timelines, Venn diagrams are more memorable than bar charts, graphs, maps, tables. It can also help to include easily-recognizable distinct objects like people, animals, cars. Psychological studies have shown that these small tweaks improve our ability to process and remember data.

Poor presentation has long plagued governments and international organizations. Compared to media outlets, these institutions rarely use diagrams. It’s no coincidence that a visualization of how epidemics spread became the most popular article ever on the Washington Post website. During pandemics, presentation choices are not aesthetic. They are existential.

Tech outreach. Governments need to communicate with their constituents where they are–and increasingly they’re on YouTube, Facebook, and other social media networks. Fortunately, those platforms are now highlighting information credible health institutions. But this should have taken hours—not weeks—to put in place. Beyond that, misinformation and rumors continue to run rife on platforms, often with real-world consequences. The widespread conspiracy theory in the UK that 5G caused or exacerbated the pandemic inspired multiple damaging attacks on 5G masts. In the U.S., some of the misinformation comes from the top, such as Trump’s dangerous claims about the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine or his musings about disinfectants. Government communications need to work with tech platforms to counteract misinformation campaigns, rather than compound them.

Media outreach. In addition to tech outreach, governments also need to continue reaching out to mainstream media as well. Staff should have ready contacts with media outlets, agreements on when their ads can supersede other buys, and a deep understanding of the latest research on effective communications. South Korea’s strategy, for example, expertly uses myriad channels: daily press briefings, websites, ads on radio, TV, and newspapers. Media consumption can increase and change quite dramatically during a disaster, with many turning back to older habits of tuning into live TV. From March 16 to 20, the seven cable news networks saw a 73 percent increase in live viewers versus the same week in 2019.

Direct outreach. During a pandemic, emergency communications are also essential. The communications unit would also be responsible for directly communicating with individuals via secure text messages.

Religious outreach. Finally, the current crisis has made clear that government communications would also need to prioritize religious outreach. Coronavirus became a mass outbreak in South Korea through members of Shincheonji, one church group whose services cram together hundreds of people for hours at a time. It seems that Shincheonji leaders tried to conceal the number of cases, which contributed to further spread in that area. In the United States, religious communities have also served as key points of transmission (as in the case of a church gathering on the Navajo Nation) and are in some cases resisting public health orders (as in the evangelical Liberty University ordering students back to campus amid the outbreak).

To avoid this, the government needs strong networks of communication with religious leaders that can be activated as soon as a potential epidemic emerges. Because they are typically more trusted by their communities than politicians, religious leaders can ensure far greater compliance by informing their congregations. And these networks can then facilitate swift information-sharing back to health authorities. If health authorities can build relationships with religious communities over years, it will make compliance easier to achieve when emergencies arise.

Building communications infrastructures and information networks takes time but is not particularly expensive. A communications unit would cost less than the National Security Council Global Health Security directorate that was dissolved in 2018 to save costs. But a billion spent preparing for a pandemic can save trillions in the long run. More importantly, effective communications can save thousands of lives.

Heidi Tworek is an associate professor at the University of British Columbia and a non-resident fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Facebook and Google, the parent company of YouTube, provide financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why the U.S. needs a pandemic communications unit

April 29, 2020